I’m a member of the Historical Arms Society of Tucson, and our group is curious if the movies are correct about how many stand-up gunfights took place on the frontier. Our consensus is we don’t think they happened much at all in the Old West.

I’m a member of the Historical Arms Society of Tucson, and our group is curious if the movies are correct about how many stand-up gunfights took place on the frontier. Our consensus is we don’t think they happened much at all in the Old West.

-Kevin Mulkins of Tucson, Arizona

February 8, 1887 • Luke Short vs Long-Haired Jim Courtright

Long-Haired Jim Courtright strides into the White Elephant Saloon in Fort Worth, Texas, and has words with co-owner Jake Johnson. Luke Short, the other owner, is called down from the game rooms and brought into the discussion.

The three men leave the saloon and walk down the sidewalk, stopping outside the Ella Blackwell shooting gallery. Courtright, owner of the T.I.C. Detective Agency, demands money for protection. Short demurs, claiming, with some authority, that he can protect himself without outside muscle.

Short has been standing with his thumbs in the armholes of his vest. When he drops his hands, an alarmed Courtright says, “You needn’t be getting out your gun.”

Short replies, “I haven’t got any gun here, Jim,” raising up his vest to illustrate.

Courtright pulls out his own pistol, but fails to pull the trigger (it is later learned that a cylinder jammed). Short fires his now-drawn gun and a bullet strikes Courtright; he then pumps four more bullets in Courtright as he falls.

This is the version of events as told by Johnson. If other issues were raised during the discussion, they died with Courtright.

April 5, 1894 • Bass Outlaw vs John Selman

Bass Outlaw is drunk. This isn’t news. He’s been described by fellow Texas Ranger Alonzo Oden as “so kind…more sympathetic, more tender, more patient than all of us when necessary.”

Except, Oden cryptically adds, “Bass [can’t] leave liquor alone, and when Bass [is] drunk, Bass [is] a maniac.”

While in El Paso, Texas, to testify in court, Outlaw is in maniac mode at Tillie Howard’s sporting house. Ruby, one of the girls, takes him by the hand and escorts him to her room. A few hours later, he emerges and appears “more tender.”

Outlaw goes out to Utah Street, where he meets Constable John Selman and Frank Collinson. During their conversation, Outlaw becomes angry and makes threats against U.S. Marshal Dick Ware. Selman tries talking Outlaw into going to his room to sober up.

Instead, Outlaw decides he wants an encore with sweet Ruby. To humor him, Selman and Collinson walk him back to Tillie’s and wait for him in the parlor while Outlaw tries to rustle up a rematch.

As Selman and Collinson talk, they hear a shot. (One report states it comes from the water closet.) Selman smiles, then says to Collinson, “Bass has dropped his gun,” and Selman leaves to investigate.

Meanwhile, Tillie bursts from her apartment, runs to the back of the building and blows a police whistle. Hearing the alarm, Outlaw chases Tillie into the yard and attempts to take away her whistle.

Texas Ranger Joe McKidrict, who’s in town to testify before a federal grand jury, has heard the shot and now hears the whistle. He starts for the scene of the disturbance.

Selman steps onto Tillie’s back porch just as Ranger McKidrict enters the backyard. “Bass, why did you shoot?” McKidrict asks.

“It was an accident, Joe,” Selman says. “He’s all right.”

Turning, Outlaw snarls, “You want some too?” as he pushes his pistol against McKidrict’s head and pulls the trigger. The bullet strikes the Ranger above the left ear. As McKidrict falls, Outlaw shoots him in the back.

Selman jumps from the porch, but before he can draw his weapon, Outlaw fires at the lawman’s face. The bullet just misses Selman’s ear, and the gunpowder sears his eyes, all but blinding him.

Falling backwards, Selman pulls his pistol and fires by instinct, his vision so impaired that his target is a blur. Selman’s shot hits Outlaw just above the heart, tears through his lung and emerges beneath his right shoulder.

Outlaw totters backwards, firing twice. One slug hits Selman above the right knee, the other rips through his thigh and severs an artery. Outlaw falls over a fence and then makes his way onto Utah Street, where he surrenders to Texas Ranger Frank McMahon.

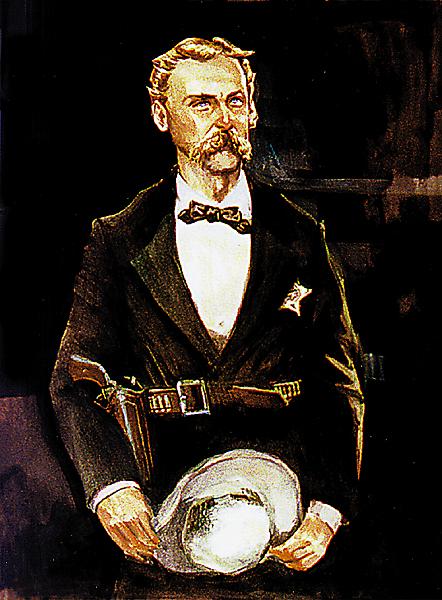

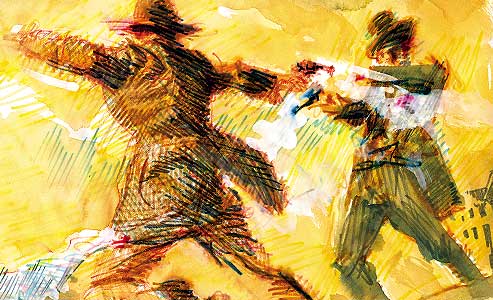

April 14, 1881 • Dallas Stoudenmire vs George Campbell

Out in the West Texas town of El Paso, ex-Marshal George Campbell is flat-out looking for trouble. “Any American that is a friend of Mexicans,” he booms, “ought to be hanged!”

Constable Gus Krempkau turns red. He has just finished assisting a group of Mexicans into the U.S. “George,” says Krempkau, as he slides his rifle into the scabbard aboard his riding mule, “I hope you don’t mean me.”

“If the shoe fits,” hoots Campbell, snapping his fingers in the air for emphasis, “then wear it.”

A drunk Campbell then turns to grab the reins of his mule, which are tied to a tree.

Another drunk bystander, Johnny Hale, steps forward and bellows, “Turn loose, Campbell, I’ve got him covered.”

Hale instantly fires, and the bullet hits Krempkau near the heart, before exiting through his lungs.

Across the street, the Globe Restaurant doors blow open, and Marshal Dallas Stoudenmire emerges with a pistol in each hand. Close behind him is his brother-in-law, Doc Cummings, toting a shotgun.

As he takes in the scene on the fly, Stoudenmire steps lively into the street and snaps off a quick shot at Hale, who ducks behind an adobe pillar. Unfortunately, the marshal’s shot misses Hale and hits a Mexican citizen who has just bought a sack of peanuts.

Hale pokes his head around the pillar. Stoudenmire’s second shot hits him in the head; he collapses, dead.

Drawing his own pistol, Campbell hastily backs into the center of the street and loudly says, “Gentlemen, this is not my fight.”

A dying Krempkau grits his teeth and squeezes off shots at Campbell. The first bullet smashes into the ex-marshal’s pistol and breaks his wrist. Campbell yells out and drops to the ground to pick up his revolver. Krempkau’s next bullet hits Campbell in the foot.

Defending his mortally wounded constable, Stoudenmire fires at Campbell. The bullet enters Campbell’s stomach, causing him to drop his gun a second time, as he topples face-down.

When Stoudenmire rolls Campbell over, Campbell sputters, “You big son-of-a-bitch, you murdered me!”

The fight is over.

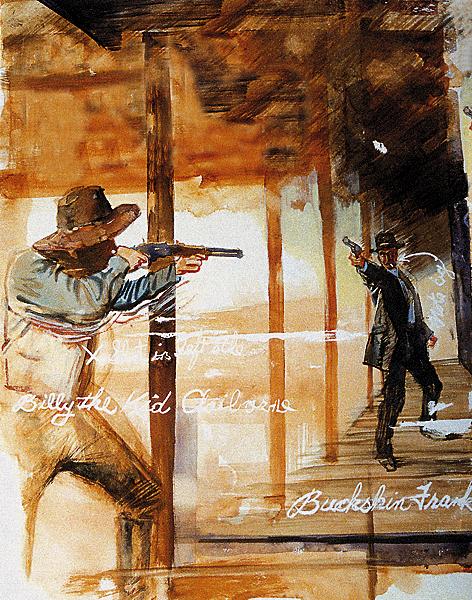

November 14, 1882 • Billy “the Kid” Claiborne vs Buckskin Frank Leslie

It’s 7:30 a.m. on a Tuesday, and Buckskin Frank Leslie is talking to several friends in the Oriental Saloon in Tombstone, Arizona. Billy “the Kid” Claiborne saunters in and begins insulting Leslie, who is the head bartender of the saloon’s tony gambling hall. Leslie is currently off duty.

After enduring several abusive remarks, Leslie takes Claiborne aside and says, “Billy don’t interfere, these people are friends among themselves, and are not talking about politics at all, and don’t want you about.” (Some evidence suggests Leslie and his cronies were discussing a recent close election for county sheriff between Dave Neagle, Jerome Ward and Larkin Carr; Ward won.)

Leslie rejoins his friends, but Claiborne, who is obviously drunk, returns and starts in on Leslie again, using “exceedingly abusive language,” Leslie claims.

A fed up Leslie takes Claiborne by his coat collar and leads him to the front door, telling him not to get mad because it’s for his own good.

As they reach the sidewalk, the hot-headed cowboy pushes Leslie away. Shaking his finger at the dapper dandy, Claiborne says, “That’s all right Leslie, I’ll get even with you.”

Shortly afterwards, Oriental bartender W.J. Mason leaves work. On Allen Street, he encounters Claiborne, who is still fuming. Having witnessed the altercation between Claiborne and Leslie, Mason tells Claiborne to cool off. As a gesture of goodwill, he invites the red-headed youngster to join him for a fish breakfast. Claiborne refuses the offer and tells Mason that instead, he is going to retrieve his Winchester and “settle the matter at once.”

Minutes later, Otto Johnson sees Claiborne steaming toward the Oriental, with a holster over his left shoulder and a Winchester rifle in his right hand.

William Henry Bush, a bootblack, tries to dissuade Claiborne from his mission, but he gets a terse reply: “No, you black son of a bitch, I will kill you.”

Informed by Johnson of the threat outside, Leslie coolly picks up a pistol, walks to the side door that fronts on Fifth Street and peers out toward the corner. He sees almost a foot of rifle barrel protrude from the end of a fruit stand, which is abutting the sidewalk at Fifth and Allen.

Leslie quietly closes the door behind him and walks out on the sidewalk. He quickly steps in the street to look around the fruit stand, to make sure it is Claiborne, before he steps back on the sidewalk and says, “Billy don’t shoot. I don’t want you to kill me, nor do I want to have to shoot you.”

Before Leslie can say anymore, Claiborne raises his rifle and fires, but the bullet misses. Leslie returns the fire and hits the left breast of Claiborne, who doubles over.

As Leslie advances on his prone adversary with his pistol at full cock, a police officer runs up and disarms Leslie, placing him under arrest. Leslie tells the officer, “I am sorry. I might have done more, but I couldn’t do less.”

Eyewitness George Parsons notes in his journal, “Frank didn’t lose the light of his cigarette during the encounter. Wonderfully cool man.”

Claiborne is taken to the nearby office of Dr. Willis, who describes the bullet wound as entering the breast on the left side and opening in the back to the spinal column. Believing the victim to be dying (he is), Willis sends Claiborne to the county hospital. Before he goes, Claiborne tells the doctor, “Leslie is a murdering son of a bitch to shoot a man in the back.” Unmoved by the claim, Willis later testifies he’s confident Claiborne “received the wound in the front.” A coroner’s jury agrees, and Leslie is set free.

September 4, 1887 • Commodore Perry Owens vs The Blevins Boys

Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens steps onto the porch of the Blevins home in Holbrook, Arizona, and knocks on the west-facing door. The Apache County sheriff is here to serve a warrant on Andy Cooper, a horse thief. The door opens slightly, and Cooper peers out. The sheriff immediately spots an ivory-handled pistol in the outlaw’s hand.

“Andy,” Owens says, “I have a warrant for you. Let’s have no trouble.”

“Give me a few minutes,” Cooper replies. “I’m not ready yet.”

Cooper tries to close the door, but Owens thwarts the maneuver by pushing his boot into the narrow opening. Cooper ducks behind the door and brings his six-shooter up to fire. Without removing the Winchester from the crook of his arm, Owens fires blindly through the door. His lucky shot hits Cooper in the pit of the stomach.

As he backs up, the sheriff levers his Winchester, ejecting the spent shell and slamming another into the breech. He quickly covers all the windows and doors in anticipation of other assailants.

A woman screams. Before Owens can react, a second door opens slightly and the barrel of a six-shooter protrudes and fires about four feet from the lawman. The bullet just misses Owens and, instead, hits a horse tied to a cottonwood tree in front of the house. The terrified horse breaks its reins, runs a short ways and then topples dead in the street.

A third assailant, John Blevins, attempts to take cover behind a door, but Owens fires another intuitive shot, hitting John in the shoulder and sending him crashing to the floor.

Owens scans the house through his rifle sights, watching for an attack from any and all corners. He hears a noise, which he recognizes as a window being opened. Owens runs from the front door to the front window, where he sees Cooper on his knees, about to get a shot off through the narrow slit. The sheriff fires again, and the bullet tears through the thin board siding, hitting an already wounded Cooper in the right hip.

So far, the sheriff’s three shots at invisible targets have produced three direct hits.

As Owens levers another cartridge into his rifle, he hears a woman pleading with someone inside the house. A commotion ensues, with more pleading, and then the front door opens. Fifteen-year-old Samuel Houston Blevins boldly steps out, brandishing Cooper’s pearl-handled pistol and vowing to “get” the sheriff. Owens’ fifth shot hits the boy squarely in the chest. The lad drops dead on the doorstep.

His every sense on high alert, Owens stands alone in front of the house, waiting and listening. He has no idea how many more men are in the house. His keen ears catch a noise on the eastern side of the house. He runs to the corner of the building, catching Mose Roberts, who is climbing out a window with a pistol in his hand. Owens fires, and the bullet hits Roberts in the chest.

The sheriff chambers another cartridge. By now, the screams and wails inside the house are dreadful. After a few anxious minutes, Owens senses that no one else will be coming out to fight.

Satisfied he has finished his work, the sheriff walks up the street toward the livery stable, where he meets several townspeople coming his way.

“Have you finished the job?” A.F. Banta asks.

“I think I have,” Sheriff Owens curtly replies.

July 17, 1870 • Hickok vs The 7th Cavalry

Deputy Marshal Wild Bill Hickok is conversing with the bartender in Paddy Welch’s Place in Hays City, Kansas, when, without warning, two 7th Cavalry troopers attack Hickok from the rear, pinning his arms and wrestling him to the floor. Later, a newspaper reports that “five soldiers attacked Bill.”

Of the two known troopers, Jeremiah Lonergan, a “pugilist” and powerful man, pins Hickok and does everything in his power to keep Hickok’s arms away from his body . . . and his pistols.

An eyewitness claims that a second soldier, John Kile, whips out a Remington pistol from underneath his blouse, “puts the muzzle into Wild Bill’s ear and snaps it.” The pistol misfires.

Amid the yelling and ensuing commotion, Hickok and the two soldiers grapple on the floor, each trying to get an advantage. (At some point, Hickok receives a leg wound; history does not record whether he is shot or merely injured in the scuffling.)

In spite of Lonergan’s best efforts, Hickok removes one pistol from his holster and fires a round, hitting Kile in the wrist. A second round hits Kile in the side, and he rolls away in agony.

Lonergan desperately fights for his life as he tries to keep Hickok’s pistol barrel pointed away from him. Pushing against the much larger man, Hickok fights with all his might, finally turning his pistol far enough to fire. The resulting shot hits Lonergan in the knee cap.

Stunned, Lonergan gives up his grip and joins Kile on the disabled list. Hickok wastes no time as he scrambles to his feet, “makes tracks for the back of the saloon,” jumps “through a window, taking the glass and sash with him,” and makes good his escape.

When news of the gunfight reaches Fort Hays, a number of troopers seize their guns, head for Hays City and search all the “saloons and dives,” but they can’t find Hickok.

March 25, 1882 • Billy Breakenridge and Posse vs Zwing Hunt and Billy “the Kid” Grounds

At 8:20 p.m., a heavy rap on the door disrupts the quiet of the Tombstone Milling and Mining Company office in Millville, across the river from Charleston, Arizona. Four employees are inside: W.L. Austin, George W. Cheyney, F.F. Hunt and Martin R. Peel.

The door flings wide open, and two masked men wielding rifles enter. Without any commands (The Tombstone Epitaph reports: “no order to ‘hold up’ was given and no words spoken”), the two intruders open fire. The first shot hits Peel, as he gets up from his chair, striking him near the heart. It’s fired at such close range “that his clothes [are] set on fire.”

The other assailant fires at the three men behind the counter, but the slight delay between the two shots allows them to dive down, so the shot misses.

Both assailants flee. As they run to their horses (eyewitnesses claim a “Confederate” held their horses “a few hundred yards from the office”), one of the shooters loses his white hat.

A $500 reward is authorized for the “apprehension of the person or persons who murdered M.R. Peel.” Peel, aged about 26, was a native of Texas.

Word reaches Tombstone that two of the suspected killers, Zwing Hunt and Billy Grounds, are holed up at the Chandler Milk Ranch east of town. Deputy Sheriff William Breakenridge wants to go alone, but an official insists he take along two miners and a jail guard for insurance. (Sheriff John Behan and his cowboy posse are away, chasing the Earps.)

Breakenridge and his posse reach the milk ranch just before daylight. After tethering their horses, they creep up and surround the main house. Two approach the back door, while Breakenridge and E.H. Allen approach the front.

“Just as we got there,” Breakenridge later writes, “I heard [John A.] Gillespie knock on the [back] door. When asked who was there, he answered, ‘It is me, the sheriff.’ The men inside opened the door and shot [Gillespie] dead and shot [Jack] Young through the thigh. Neither Young nor Gillespie ever got a chance to fire a shot.”

Breakenridge jumps behind a small tree, narrowly dodging a bullet. He covers the front door, waiting for the outlaw who shot at him to reappear. When he does, the deputy fires one barrel of his shotgun into the opening. He later recalls, “Just as I fired I remembered an old adage always to aim low in the dark, and I pulled down thinking I would hit him in the stomach. But I hit [Grounds] in the head and heard him strike the floor.”

Meanwhile, Hunt has been shot through the lungs. He tries to flee, but Breakenridge tracks him up an arroyo and, in the gathering daylight, he corrals him.

December 27, 1894 • Curry vs Pike Landusky

Celebrating the holidays in Jacob “Jew Jake” Harris’s saloon in newly named Landusky, Montana, the town’s namesake, Powell “Pike” Landusky, is holding forth with his neighbors and friends at around 10:30 in the morning.

Melting snow has clogged the stove pipe in the store/saloon, and a young kid has been brought in to clean it out. Harris hobbles around behind the bar on his one leg (the other was lost during a gunfight in Great Falls). He sets a bottle and glass on the bar in front of Landusky, who gets ready to take his first drink of the day.

Stepping in out of the cold, cowboys Lonie (pronounced LOne-E) Logan and Jim Thornhill, his neighboring rancher and partner, pass through the saloon into the clothing store. Their mission is to neutralize a gunman named Charles Hogan (a lunger). Thornhill orders 25 cents worth of apples as he and Lonie take up positions to handle Hogan when the fireworks start.

A few moments later, as planned, Harvey Logan, a.k.a. Kid Curry, comes in the front door. Kid Curry’s younger brother John stays outside and guards the front door with a Winchester. Kid Curry advances straight toward Landusky and aggressively slaps him on the shoulder, knocking the bottle out of his hand. When Landusky turns, Kid Curry punches the noted brawler in the face with all his might.

When the two clinch, both Lonie and Thornhill step forward, yelling out, “Fair fight!” Landusky’s friends, including Hogan, are intimidated and hold back from joining in.

As the men punch each other and scuffle, Kid Curry’s pistol falls out of his coat pocket onto the floor. Thornhill fetches the Colt .45 by the barrel so no one can accuse him of assault. (Landusky’s friends later allege Thornhill waved it at bystanders, warning, “The first man that makes a move will be killed.”)

Landusky is a grizzled, experienced brawler. He gets the advantage on Kid Curry, landing on top of the smaller man while trying to gouge out his eyes. Kid Curry manages to get on top, too, pummeling the much bigger man until Landusky cries out “Enough!”

A mining friend of Landusky, Thomas Carter, asks Lonie to intercede, saying that Landusky has clearly had enough. Lonie allegedly replies, “He has not got enough for what he has done to us.”

Thornhill finally convinces Kid Curry to let go of Landusky. The combatants stagger to their feet, and Landusky reaches in his coat and pulls out a semi-automatic pistol (an 1893 Borchardt). As he does, he calls Kid Curry a coward for attacking him without cause. (Landusky doesn’t fire his pistol; one account claims he does, but either the gun misfired or he failed to chamber a round before he fired.)

Thornhill pitches the .45 to Kid Curry, who fires a shot in Landusky’s gut. Curry fires three times in all, with two slugs hitting Landusky and one going awry. Landusky falls to the floor and dies in about five minutes.

Brother John rounds up the cowboys’ wagon, and the four make their escape.

May 10, 1871 • Harry Morse vs Juan Soto

It’s a warm day as Sheriff Harry Morse and Deputy Sam Winchell approach an isolated ranch house in California’s Coast Range. Reining up at the outer perimeter of a rock corral, they dismount and ask a vaquero, who is working in the corral, for a drink of water.

Following the worker into the house, Morse and Winchell encounter a roomful of natives. Morse is stunned as he immediately recognizes the outlaw they are looking for: Juan Soto—bandido supremo—who is sitting at a table, talking with two other men.

The sheriff jerks his pistol and barks, “¡Manos arriba!” [Put up your hands!]

But Soto doesn’t move, even after Morse repeats the command two more times. Yanking a pair of manacles from his gun belt, Morse hands them to his deputy with orders to handcuff the brigand.

Paralyzed with fright, Winchell doesn’t move.

“Put them on him!” Morse angrily snaps. Seconds tick by, and still no one moves.

“Then cover him with your shotgun,” Morse barks, “while I do it!”

Instead, Winchell bolts toward the door, leaving Morse to fend for himself.

Seizing the moment, a “muscular Mexican Amazon” grabs Morse’s shooting arm, while another outlaw grabs his left. “¡No tire en la casa!” they both shout. [“Don’t shoot in the house!”]

As Morse grapples with his assailants, Soto leaps behind one of his compadres and begins to unbutton his long soldier coat so he can retrieve his pistols, which are in his belt under the coat.

Morse breaks free from his attackers and levels his pistol at Soto’s head, but the arm jockeys spoil Morse’s aim. When Morse fires, his shot tears off Soto’s hat and thuds into the wall. (Morse later claims he didn’t want to shoot an innocent bystander.) The billowing gunpowder smoke adds to the confusion in the dimly lit room, but it allows Soto to seize one of his revolvers and go after Morse, who has just cleared the door.

Out on the porch, Morse tries to sprint to his horse so he can retrieve his rifle from its scabbard, but Soto is right behind him. Morse quickly realizes he won’t make it. Turning, so as not to be shot in the back, Morse drops to the ground in an effort to dodge Soto’s imminent point-blank shot.

From a nearby hill, Sheriff Nick Harris sees Morse fall, “but quick as a flash, [Morse springs] erect and fire[s]. Soto, advancing with a bound, [brings] his pistol down to a level and [fires] again, and Morse [goes] through the same maneuver as before.” To Harris, Morse looks like he has been hit by all four rounds.

On the final exchange, however, when Soto raises his weapon to cock it, Morse’s bullet strikes Soto’s pistol underneath the barrel. The bullet wedges against the cylinder and jams the gun. The force of the lead ball violently drives the barrel of Soto’s own gun into his face, briefly stunning him.

As Morse scrambles to his horse, he jerks his Model 1866 Winchester rifle from the scabbard. When he turns, he sees Soto has retreated inside the house. (Once Winchell sees the outlaw escaping, he sends a load of buckshot in his direction, but the deputy misses.)

After charging his mount down the slope at a dead run, Sheriff Harris reins in, dismounts, pulls out his Spencer rifle and joins Morse.

Following a pregnant pause, two men emerge from the house, heading for a lone horse that is hitched to an oak tree 40 yards out. Sheriff Harris takes aim at the man wearing the long, blue Army coat, but Morse knocks up the barrel before Harris can fire. Morse realizes that Soto has exchanged coats with a comrade and is donning his friend’s hat to throw off the officers. (Unbeknownst to them, the outlaw is also sporting three fresh revolvers.)

Morse raises his rifle to shoot the escape horse, but the mount breaks free and evades Soto’s grasp. The horse is undoubtedly spooked by the firing. Soto then rushes headlong to a second horse that stands saddled some 200 yards north.

“For God’s sake, Juan, throw down your pistols!” Morse yells. “There has been shooting enough!”

Ignoring the plea, Soto continues charging toward freedom. Although Soto is virtually out of range at 225 yards, Morse flips up his gun sight, aims high and pulls the trigger. Incredibly, the “Hail Mary” bullet hits Soto with a sharp click and tears through his right shoulder.

Soto staggers, then the badly wounded outlaw turns to rush his adversaries. He runs headlong with his pistols raised, hoping to make it into firing range. Sheriff Harris shoots at Soto and misses, sending a clump of grass flying. Morse chambers another round and takes a careful bead. At more than 100 yards from its target, the big ’66 booms, and its spinning bullet makes a long, low arc, smacking into Soto’s forehead just above the eyes. The bandit topples dead on the spring grass.

October 1, 1917 • Frank & Gladys Hamer vs Gee McMeans & H.E. Phillips

Frank Hamer wants to go home. The Texas Ranger has just testified at the Callahan County Courthouse in Baird, Texas, in a murder trial, and the case has been continued. Two men, waiting by a drugstore, warn Frank not to pass through Sweetwater on his way home—men are waiting there to kill him.

Frank has no intention of changing his route, although he tells none of his car passengers about the threat. He does strap on an extra revolver, a .44 Smith & Wesson, to complement his .45 Colt.

Frank’s traveling companions are his wife Gladys (who is three months pregnant), his brother Harrison and a witness in the court case, Emmett Johnson. He points the car toward their home, Snyder.

As Frank drives by a second-story building in Abilene, he spots a lawyer friend of former Texas Ranger and Sheriff Gee McMeans’ staring down out of his office, smiling a smug smile.

At about 1:30 p.m., on the approach to Sweetwater, a tire on the Hamer car goes flat. Frank pulls into a garage located on the southeast corner of the town square.

Harrison and Emmett head across an alley to “see a man about a horse” (go to the bathroom). Gladys remains in the car. Frank enters the empty garage. Finding no one inside, he starts to exit when McMeans jumps out from behind a door and shoots Frank point-blank, yelling, “I’ve got you now, God damn you!”

The bullet drives Frank’s watch chain deep into his left shoulder, incapacitating his normal gun hand. He grapples with the gunman with his right hand, but McMeans gets off another shot; the second bullet tears into Frank’s leg.

Gladys is in the car when she spots a man with a shotgun coming toward Frank on the street. She grabs a .32 pistol off the seat and fires at the shotgunner, but her shot misses. The man, H.E. Phillips, a known gun toter in Texas, squawks and ducks behind an automobile. Every time he tries to rise, Gladys sends another bullet his way, until she empties the magazine. As she ducks down in the seat to reload, the shotgunner runs toward Frank.

Frank is still wrestling with McMeans and starts slapping the shooter in the head with his open hand. From the corner of his eye, Frank sees the shotgun shooter approaching. McMeans breaks free, the shotgun roars and the concussion of the blast staggers Frank as he falls to his knees.

“I got him! I got him!” the shooter yells in triumph, only to see Frank lunge to his feet. (The blast, fired from two feet away, shredded Frank’s hat, missing his head by inches.)

McMeans and the shotgunner run toward a waiting car. Frank runs after them, stumbling, but regaining his feet and pulling a gun with his right hand. He reaches the shooters’ getaway car just as McMeans fetches a pump shotgun from inside. As he turns, Frank puts a bullet through his heart, killing him.

Behind the vehicle, the shotgunner crouches beside McMeans’s body, the smoothbore still in his hands.

“Get up!” Frank yells. “Fight me like a man!”

The shotgunner scrambles to his feet and runs. “Turn around, damn you!” Frank screams.

His brother Harrison runs up, raising his rifle toward the fleeing man. Frank knocks the barrel skyward as Harrison squeezes off the shot. “Don’t shoot him in the back! Leave him!”

Gladys runs up and takes her husband around the waist, his blood oozing onto her dress. Several other men run toward the scene.

“Somebody get a doctor!” Gladys yells. “My husband’s been shot!”

This is just one of the 50 gunfights involving Frank; he will be wounded a total of 23 times and declared dead twice.

Photo Gallery

—George Parsons’ journal entry, November 14, 1882

– All photos True West Archives –

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

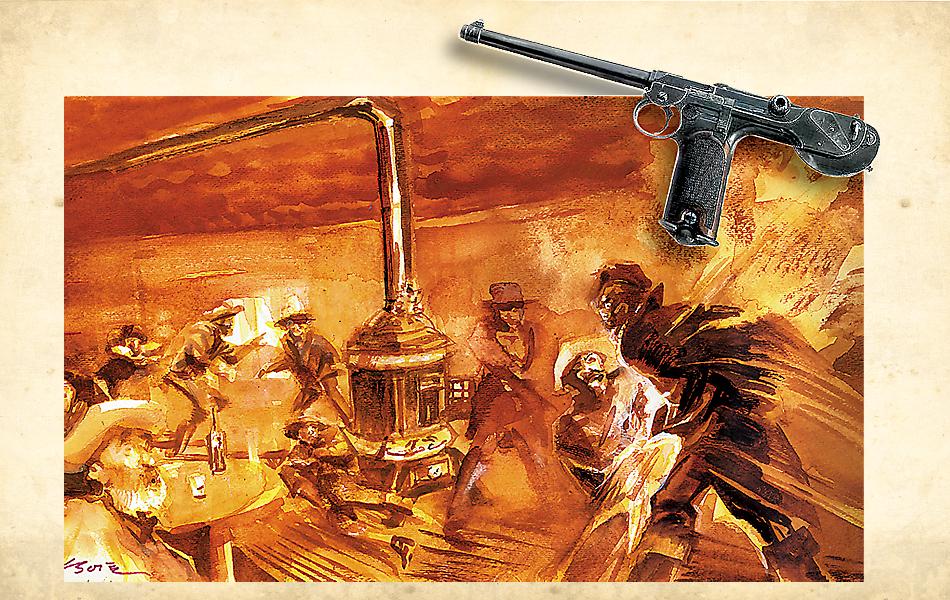

At 6 p.m., Marshal Dallas Stoudenmire (center) hears gunshots and exits the Globe Restaurant. Sizing up the scene, he attacks Hale and Campbell, who he assumes killed his constable, but he ends up killing an innocent bystander. Doc Cummings (far right), Dallas’ brother-in-law and the owner of the Globe, steps off the sidewalk with a shotgun. He fires no shots. Backing into the middle of the street, Campbell (far left) tells them, “Gentlemen, this is not my fight.”