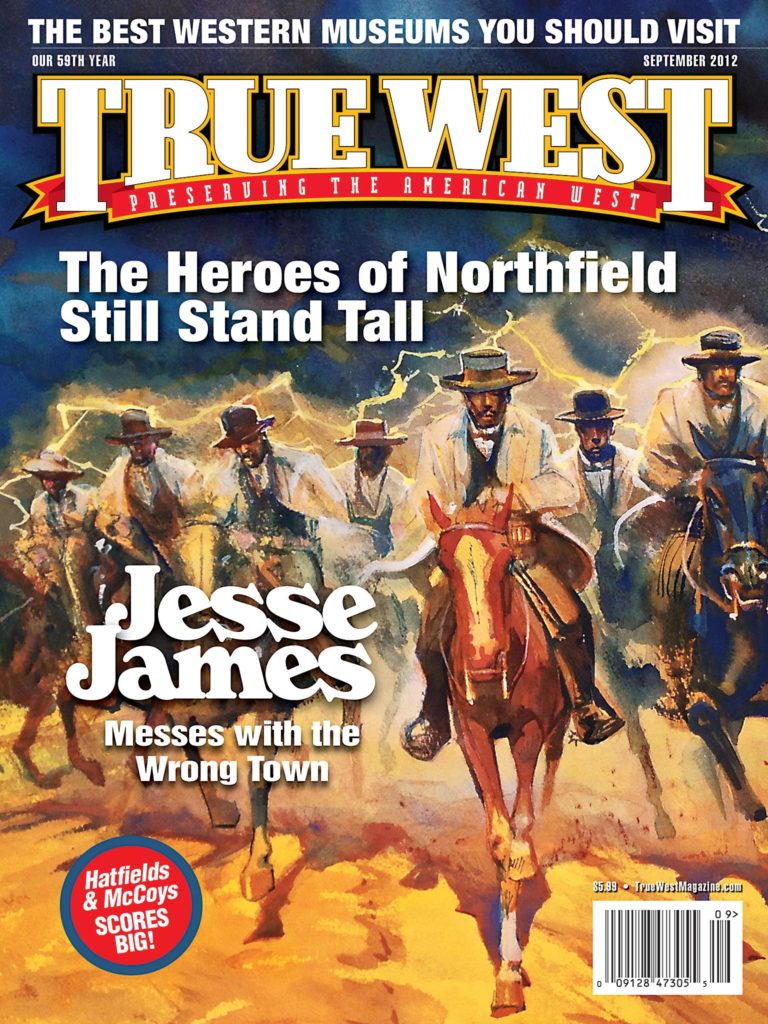

When Northfield re-enacts the James-Younger bank raid, during the Defeat of Jesse James Days this September 5-9, local historian Chip DeMann will be heading up the re-enactors. He’s among the James-Younger historians who, as Johnny D. Boggs points out in his article, still debate the particulars of the foiled bank robbery.

When Northfield re-enacts the James-Younger bank raid, during the Defeat of Jesse James Days this September 5-9, local historian Chip DeMann will be heading up the re-enactors. He’s among the James-Younger historians who, as Johnny D. Boggs points out in his article, still debate the particulars of the foiled bank robbery.

DeMann will be sharing his never-before-published research in Mark Lee Gardner’s upcoming book, Shot All to Hell. We asked him to tell us some of the highlights:

Why did the James-Younger Gang venture so far away from Missouri?

On July 7, 1876, Frank and Jesse James, Cole and Bob Younger, Hobbs Kerry, Samuel Wells (alias Charlie Pitts), Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell robbed a Missouri Pacific train at a location called Rocky Cut, near Otterville, Missouri. The total haul from the Adams and the United States Express Companies was $18,300 (equal to roughly $366,000 today).

Shortly after the robbery, the St. Louis police captured the gang’s new recruit, Kerry. After Kerry spilled his guts, Chief of Police James McDonough allowed his confession to be published.

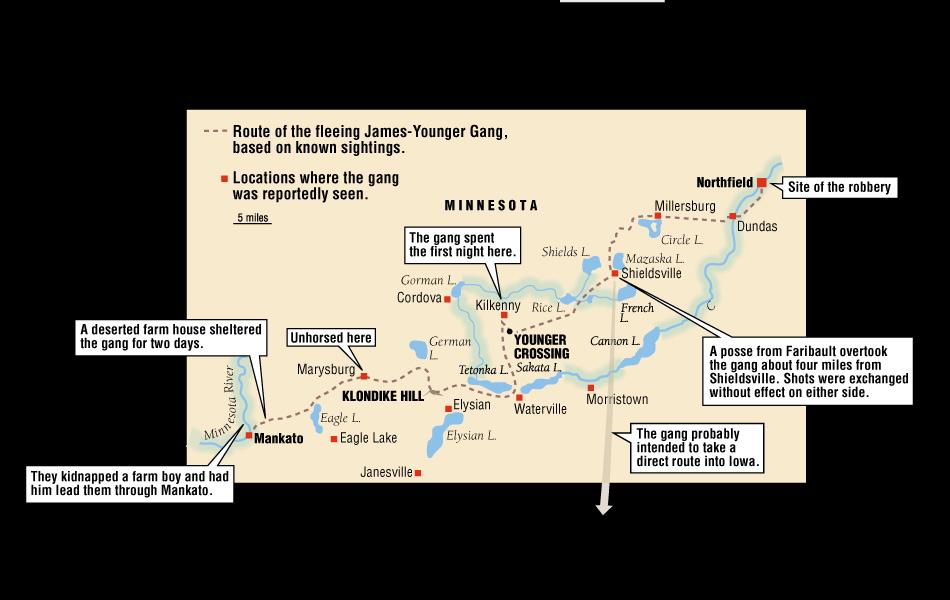

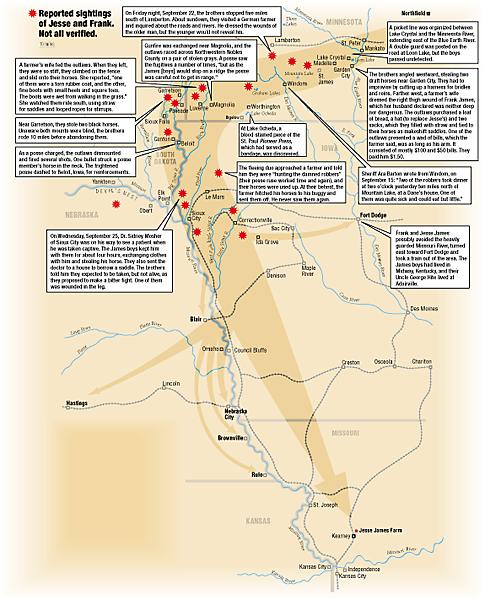

To throw off the posse, the gang members headed for Minnesota, not Texas, as Kerry had told the police. In his autobiography, Cole described the gang’s plan of action: “Accordingly, about the middle of August we made up a party to visit Northfield, going north by rail. There were Jim, Bob and myself, Clell Miller…; Bill Chadwell, a young fellow from Illinois, and three men whose names on the expedition were Pitts, Woods and Howard.”

Pitts, Woods and Howard are the only aliases Cole used in his 1903 book. He certainly didn’t conceal the identities of Frank and Jesse, describing them with their most common aliases. Frank and Jesse used Woods and Howard respectively on contracts, bills of sale and other legal paperwork, and neighbors and friends knew them by those names.

Pitts was in fact Samuel Wells. To date he is the only member of the gang we still identify with an alias. I have been trying to correct this for many years, but the public really likes his alias. I’ll keep trying.

Was there a Ninth Man?

Bill Chadwell was killed in Northfield (his September 7, 1876, death certificate is at the Rice County Courthouse). The question today is whether Bill Stiles was with the gang during the raid.

Thanks to California attorney Michael Djavaherian, we know more about Bill Chadwell, which should put to bed any suspicion that he and Stiles were the same man.

Bill Chadwell was the youngest son of William Chadwell Sr., born in Greene County, Illinois, in 1853. Greene County is just across the river from St. Louis.

Stiles had lived in Monticello, Minnesota; at the time of the Northfield bank raid, his sister taught school in nearby Cannon Falls. Stiles’s father, Elisha, was living in Grand Forks, Dakota Territory, at the time of the robbery. Responding to a letter sent to Grand Forks, asking about his son’s whereabouts, Mr. Stiles responded, “I thought he was in Texas. I suppose he got in with a lot of them damned pirates.”

When was the time lock put in place?

The week prior to the James-Younger Gang’s assault on the First National Bank in Northfield, some improvements were made. A month earlier, on August 9, 1876, the Rice County Journal had reported on the changes:

“The First National Bank of this place is having a new set of doors put into

their vault. Two doors will have to be opened before the vault is reached, each fastened with the most approved combination locks. On the inside of the vault will be placed a steel burglar-proof safe having a chronometer lock, thus avoiding the annoyance of having burglars pull the cashier’s hair to make him open the safe, as it cannot be opened until a certain hour, by anyone, the doors and safe were manufactured by the Detroit Safe & Lock Company.”

I believe that when Frank and Jesse visited the bank that last week of August, they saw the old safe, likely the original safe used by the Bank of Northfield, founded in 1865, the predecessor to the First National Bank.

Although time locks were somewhat new in 1876, the gang was aware of the bank’s improvements, based on news clippings found on the bodies of the two outlaws killed during the raid. Clell Miller’s body had an “article from the local paper here describing the Yale chronometer lock and safe just procured by the bank,” reported the Minneapolis Tribune on September 8. Bill Chadwell’s body had a “scrap of paper bearing the advertisement of Hall’s Safe, in which a burglar is pictured as giving it up on discovering the make of the safe.”

Despite having done their homework, the gang must not have realized how difficult it would be to transact business at two p.m. if all the funds were locked up.

Most assumed the gang rode horses all the way from Missouri (thus, 1980’s The Long Riders). But if they took the train to Minnesota, where did they procure their horses?

In his autobiography, Cole Younger reported: “When we split up in St. Paul Howard, Woods, Jim and Clell Miller were to go to Red Wing to get their horses, while Chadwell, Pitts, Bob and myself were to go to St. Peter or Mankato, but Bob and Chadwell missed the train…. Pitts and I bought our horses at St. Peter…. I bought two horses, one from a man named Hodge and the other from a man named French….”

Meanwhile, Jesse and Frank James, Jim Younger and Clell Miller arrived in Red Wing by train on August 26, and registered at the National Hotel as J.C. Hortor, Nashville; H.L. West, Nashville; Charles Wetherby, Indiana; and Ed Everhard, Indiana. After eating dinner at the National Hotel, they purchased two sorrel horses from A. Seebeck and two more horses from J.A. Anderberg.

On September 8, the day after the raid, the Rice County Journal reported: “A.O. Whipple received a telegram from Sheriff Chandler, of Red Wing, that four of the gang got their outfit in that city, including horses for each, the buckskin, the splendid bay, and two others, and four saddles and bridles they purchased of Pet. Watson, who formerly lived there.”

What happened to the gang’s horses?

On September 14, the Rice County Journal informed its readers that all of the horses have been accounted for: “Passing over the thousand and one conflicting telegrams, and contradictory reports we come down to what is reliable. And first we say all the bandits’ horses have been captured, one dead in Northfield and two others living and well cared for in stables here, and the remaining five with their saddles were taken to Faribault last Tuesday night. They were found tied in the big woods, and were getting hungry.”

Earlier, on September 9, St. Paul’s Pioneer Press and The Minneapolis Tribune had reported: “The two horses left at Northfield by the bandits were in the stable. One was a powerful black nag, with a pacing gait, and the other a large bright bay, that dropped immediately into a lope when he started. This one had a terrible raw sore on his back. He was evidently a Kentucky horse, very tall and with long legs. It is a significant fact that these horses were mounted by two men named Hayes and Wheeler. They are true reformers.”

One of these horses was Chadwell’s, while the other was Miller’s. Jack Hayes and Dwight Davis followed the bandits until a larger posse could be formed. At some point during the chase, Henry Wheeler took over for Davis.

The gang must have felt demoralized, being chased by men riding two of their horses.

Did the outlaws try to get another horse for Bob Younger?

Three miles south of town, near Dundas, Hayes and Davis watched as the gang cut the harness from a team belonging to Phil Empey. The outlaws took one of the horses for Bob Younger, who had been riding behind Cole with a badly wounded right elbow. The Empey horse was soon abandoned, as Bob was not able to stay on the horse’s back.

Empey’s sister later described the theft: “It was Bob Younger who took our horse. Some people recognized the animal as the robbers were going over the Dundas Bridge and shouted at them ‘what are you doing with Phil Empey’s horse?’ They rode right on, and soon we all knew who they were, and there surely was great excitement. We got our horse back after a few weeks but he was never the same.”

How come other towns did not react sooner?

The message about the robbery was sent to Dundas, but the depot agent, Homer Roberts, was not at his post. Had he received the message, the battle might have finished in Dundas, as the bandits rode past the Archibald Mill.

What happened to the bodies of the dead outlaws?

As Henry Wheeler (who had fatally shot Clell Miller) left with the posse, he instructed his fellow Ann Arbor medical students Clarence Persons and Charles Dampier to acquire the bodies.

Persons and Dampier dug up the two bodies on the night of September 8. They were put in barrels marked “mixed paint” for shipment to Ann Arbor. A diary kept by Newton, brother of Clarence, provided the cryptic story of the grave robbing.

“Go to town to see the dead men this morning,” Newton wrote on September 8, “and I ran manure. O. helps Weeks thrash with his team and Nelly to draw straw in p.m. I finish cutting corn in p.m. C. [Clarence] does some night work tonight.”

On September 9, he wrote, “Night Clarence, Orville & Wife come home today & Albert comes at night. C. ships two barrels of mixed paint this morning to UV Ann Arbor.”

By the time of Heywood’s funeral, on Sunday, September 10, Miller and Chadwell’s bodies were on their way to Michigan. Heywood’s body had been laid to rest not far from Miller and Chadwell’s grave sites.

What question persists about the outlaw burial?

Given the claims that Wheeler and associates robbed the graves to use the bodies for medical research, the relatives of Clell Miller have petitioned the Clay County authorities, this past June, for permission to exhume Miller’s body from the Muddy Fork Cemetery in Kearney. The family would like to know for sure if the grave contains their relative’s body.

Chip DeMann is the president of the Rice County Historical Society and present-day leader of the James & Younger Gang. He often plays the role of Bob Younger in the annual re-enactment of the bank raid.hen Northfield re-enacts the James-Younger bank raid, during the Defeat of Jesse James Days this September 5-9, local historian Chip DeMann will be heading up the re-enactors. He’s among the James-Younger historians who, as Johnny D. Boggs points out in his article, still debate the particulars of the foiled bank robbery. DeMann will be sharing his never-before-published research in Mark Lee Gardner’s upcoming book, Shot All to Hell. We asked him to tell us some of the highlights: