For fans of Western movies, the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War kicked off a few months early, when True Grit opened at theaters last December.

For fans of Western movies, the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War kicked off a few months early, when True Grit opened at theaters last December.

Grizzled veteran Rooster Cogburn, we learned, was an enthusiastic member of Quantrill’s Raiders, that notorious band of Missouri guerrillas that spawned Jesse James. It also provided a home, and a means of exacting revenge against the Yankee Redlegs, for the outlaw Josey Wales.

In fact, if you were to remove one eye and add some heft to Wales, he could be Cogburn, a few years down the line. Cogburn this time around was played by Jeff Bridges, who had his own dance with the Civil War in one of his earliest pictures, 1972’s Bad Company, as the leader of a gang of young toughs who were dodging induction and roaming the countryside during the war.

But the first Cogburn was John Wayne in 1969, and Wayne had a long history with the Civil War in his career. He went up against Quantrill, renamed Cantrell, in 1940’s Dark Command, a movie that gave him the extra critical shove he needed after John Ford cast him in Stagecoach the year before. The Civil War got a lot of play in the barbed-wire banter between Doc Boone (Union) and the gallant but deadly gambler Hatfield (Confederacy) in the Ford film as well.

Despite being a Civil War scholar and peppering his Westerns with many references to the conflict, Ford never made a full blown Civil War feature until he cast Wayne, nearly 20 years later, in The Horse Soldiers, a movie that has its champions but never warranted the respect his other Westerns achieved.

In between, Ford’s terrific 1950 film Rio Grande has Wayne as a cavalry officer in post-Civil War Texas who severed his relationship with his wife (Maureen O’Hara) when he burned her family plantation while under orders from his Union commander, Philip Sheridan. Interestingly, this bit of history came straight from Ford’s wife, Mary, whose family lost its land under the exact same circumstances.

Wayne played another Union man in 1973’s The Train Robbers, but in 1969’s The Undefeated and 1970’s Rio Lobo, Wayne’s Yank forms alliances with his former foes after the surrender.

Rio Lobo was the last of four movies Wayne made with director Howard Hawks, but their first collaboration, Red River, used the decimation of the South’s economy during Reconstruction to spur Wayne’s character, Tom Dunson, to move his cattle to the markets in the north. The boy he rescued from an Indian attack before the war, Matthew Garth (Montgomery Clift), comes back from the conflict a seasoned fighter and a quick-draw artist.

Red River is an indisputable classic, both as a Western and as an American film, but it was heavily foreshadowed 10 years earlier by an interesting picture, 1938’s The Texans, which starred the young Randolph Scott (a dead ringer for Matthew McConaughey). Scott played a recently discharged Confederate soldier—along with thousands of others—at loose in a Texas overrun with slimy Northern carpetbaggers. The cattle drive in this film is launched in the dead of night when the Northern crooks are about to “tax” Joan Bennett’s land and beef. Quite a bit of Scarlett O’Hara is in Bennett’s Southern firebrand, which explains why she was on the short list to play Scarlett a year later. One or two rewrites and a better director, and The Texans might have achieved classic status. One thing for sure, you’ve never seen the Reconstruction portrayed more venomously than you do in this film.

Scott, who was born in Virginia and raised (and buried) in North Carolina, played Confederates and former Confederates for most of his career. In 1953’s The Stranger Wore a Gun, Scott is a spy for Quantrill who is sick when he sees what his fellow Missouri raiders do to Lawrence, Kansas. In 1951’s Santa Fe, Scott plays the eldest of four Confederate brothers who have lost their wealthy Virginia plantation to carpetbaggers.

What distinguishes Civil War movies from Civil War Westerns is often a simple matter of location, location, location. Except for the vast majority of Jesse James pictures, which stay close to Missouri and Kansas (pretty far West at the time), filmmakers were always trying to drag the war farther west, into New Mexico, Colorado, Texas and Mexico. Even Arizona, which saw only a single fight between the North and the South, gets a fair amount of action in Civil War Westerns.

The Outriders, a recent picture to come out of the Warner Archive Collection, has four of the more recognizable plot elements in post-Civil War Westerns. One, it takes place precisely at the point the war ends. Two, it involves a large cache of gold (an awful lot of loose gold seemed to be floating around back then). Three, it has a hero, Joel McCrea in this case, who takes a stand for honor and virtue in a changing world. Four, it takes place in a Western locale, New Mexico.

Italian director Sergio Leone, the Godfather of the Spaghetti Western, was accused of fabricating much of the Civil War campaign he portrays in his epic 1966 picture, The Good The Bad and The Ugly; the film does indeed feature a few out-of-place details. But the laugh was on the critics because the New Mexican campaign that provides the backstory, and the spectacle, of his third and final Clint Eastwood film is more accurate than most. It actually has a cameo by Brig. Gen. Henry Sibley, who was defeated in his efforts to capture the Southwest for the Confederacy. The DVD includes an excerpt from a fascinating documentary about Sibley, “The Man Who Lost the Civil War.”

Eastwood is no stranger to Civil War Westerns. After The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, he made a grisly gothic horror Western for his other mentor Don Siegel, 1971’s The Beguiled, about a fairly nasty Union deserter who is being looked after by a house full of Southern women. The Outlaw Josey Wales has the fifth most recognizable plot device, revenge. The 1976 film also shows the North as vicious and brutal, and determined to bring Wales to justice. Looking back, it might be Eastwood’s best Western, maybe his best picture.

The revenge motif re-emerged in 2006’s Seraphim Falls, which is a long existential chase between an ex-Confederate officer (Liam Neeson) and the Union captain (Pierce Brosnan).Some of the same thinking went into 2010’s Jonah Hex. We also see in Hex the demented Confederate officer (John Malkovich) who dreams of reversing the South’s defeat by blowing up Washington with exploding yellow balls.

The post-Spaghetti Westerns did shift away from the too frequent portrayal of the defeated Southerner as a figure of sympathy. Veteran American actor Joseph Cotten played obsessive Confederates twice in two Italian pictures, 1965’s The Tramplers and 1967’s Hellbenders, but the change really started in 1964, with Rio Conchos; Edmund O’Brien plays Col. Pardee, who feeds guns to angry Apaches from Mexico.

But as far as filmmakers were concerned, what the Civil War did was pump untold thousands of war-haunted soldiers and officers into the vast post-Apocalyptic Western landscape.

Rod Steiger as Private O’Meara, an Irish-born Confederate soldier, refuses to concede a victory to the North and chooses instead to fight, and join, the Sioux in 1957’s Run of the Arrow.

More than 30 years later, Kevin Costner, as a Union soldier in a state of post-traumatic shock, places himself in Sioux territory in 1990’s Dances With Wolves.

Confederate prisoners of war agree to cross into Mexico to fight the Apaches in Sam Peckinpah’s great 1965 classic Major Dundee, with fantastic performances by Charlton Heston, Richard Harris and Peckinpah stalwarts Warren Oates and James Coburn.

And Vera Cruz, Robert Aldrich’s 1954 Western, puts Gary Cooper in the Randolph Scott part of the bitter, defeated Southern gentleman, teamed with the utterly amoral gunslinger Burt Lancaster, in the movie that foresaw Spaghetti Westerns 10 years before they were a twinkle in Leone’s eye. But Cooper fans will remember him opposite Oscar winner Walter Brennan as Judge Roy Bean, in 1940’s The Westerner, who dies at the feet of Lily Langtry in the Confederate uniform he hadn’t worn “since Chickamau-gee.”

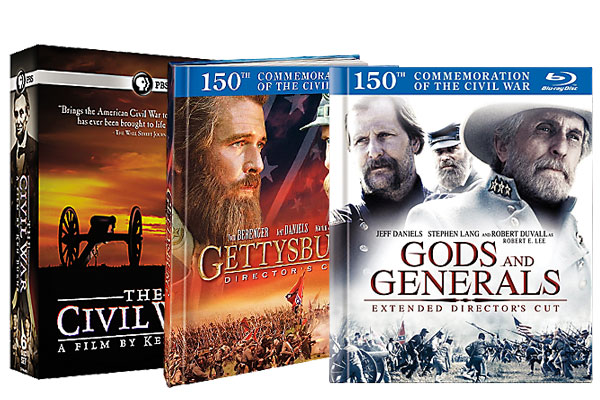

Certainly all Civil War movies aren’t Westerns, and all Westerns don’t refer to the Civil War. You won’t find Gone with the Wind, Gettysburg, Glory or Cold Mountain on the Western Writers of America’s top 100 Westerns list, even though Giant, The Last of the Mohicans and The Grapes of Wrath are listed.

But in the top 20 of that top 100, you will find Shane, The Searchers, Open Range, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Red River, True Grit (1969) and Stagecoach (1939)—all great Westerns that draw heavily on the Civil War.

One memorable character, Ethan Edwards, returns from the war, from four years with Hood and the Texas Brigade, which puts him at Gettysburg and many other grueling battles. But when he covers his dead niece with his Johnny Reb coat, off-screen, that brief gesture and a couple of throwaway lines in The Searchers say more about the war and its emotional aftermath than most other movies could manage in hours.

The South did rise again, in countless movies, TV shows, documentaries and books. With rumors of a remake of The Searchers, and the new Hell on Wheels series on AMC, perhaps it will again.