“In the bag,” he said as he opened it and removed two objects, “is the broken shell of the iron kettle, a pebble from the butte, and a piece of the sacred sage.”

“In the bag,” he said as he opened it and removed two objects, “is the broken shell of the iron kettle, a pebble from the butte, and a piece of the sacred sage.”

He held the pouch upside down and dust drifted down.

“After the bag is yours, you must put a piece of prairie sage within and never open it again until you pass it on to your son.”

–“The Medicine Bag,” by Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, from Grandpa was a Cowboy & an Indian

In her poignant 1977 short story about an unadorned leather pouch passed across generations of a Sioux family, Virginia Sneve revealed how the bag’s seemingly paltry contents, tokens of an ancestor’s vision quest, were important in providing wisdom and strength to

its owner.

Medicine bags, parfleches, possibles pouches and other sacks of all sizes preserved and transported all kinds of items for American Indians, from food to tobacco to totemic relics. Even after the arrival of the Europeans and the efficient, streamlined pockets on their pants, shirts and coats, these bags still suited the needs of Indians.

Purses and handbags, satchels and briefcases—and, yes, pockets—are the contemporary equivalents of such simple carriers. The fanciest purses and the most ordinary pockets have a common ancestor in the humble pouch. The English words “pouch” and “pocket” came from the old French pouque, which became “poke” in Norman England. The proverbial “pig in a poke” was a cautionary tale about verifying the contents of a closed sack.

Anybody who had something to carry usually put it in a leather or cloth bag. The contents ranged from coins to food to snuff, depending on one’s station and appetites. Smaller pouches were hung from a belt or girdle. To keep pouches extra secure, they were carried inside the clothes. To improve access, slits were made in the garments; in the 15th century somebody sewed the poke to the slit and created the first “poket.”

The concept of dressing up a pouch as a statement of wealth or status didn’t take hold in Europe until the 1300s. Over the next couple of centuries, both men and women wore or carried fancier purses or clutches, often decorated with embroidery. Embroidered purses among women suggested their skillset in that craft and their marriageability.

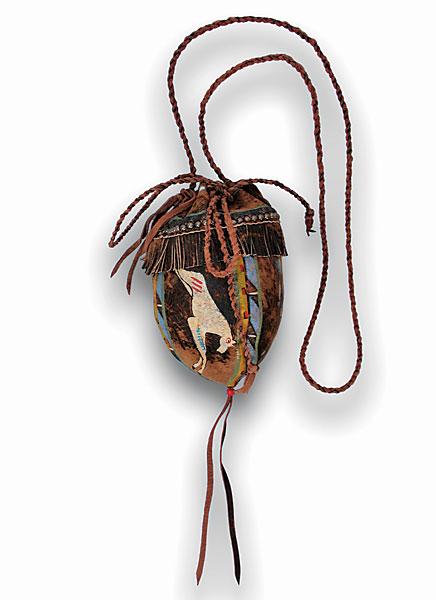

Decorated bags and other carriers were not exclusive to Europeans. From Chinese silk purses to West African goatskin gris-gris, adornments to beautify, sanctify or protect date back millennia in most other cultures. Likewise, American Indians often decorated their larger bags and parfleches with animal motifs that were more about spirituality than artistry. Geometric patterns, many of which represent animal or other spirits, were commonly depicted in paint, bones, quills, stones and, after the Europeans arrived, trade beads.

Hair-on leathers, fringe, beadwork and other decorative touches distinguish Western purses from other fashion categories. Primitive designs are back in vogue with mainstream fashion, which may have contributed to the recent sellout of American West’s handbags on ShopNBC. ShopNBC reported it was the network’s most successful handbag launch and has invited American West to return in July.

The medicine bag in Sneve’s short story represented the essentials of the traditional Indian family’s survival in a brave’s new world. The size, styling and contents of contemporary purses and handbags also reveal much about their owners’ lives and priorities. Such bags may not contain prairie sage dust to signify the passing of a person’s life, but they can pay homage to the spirit and artistry of America’s Indian heritage.

Photo Gallery

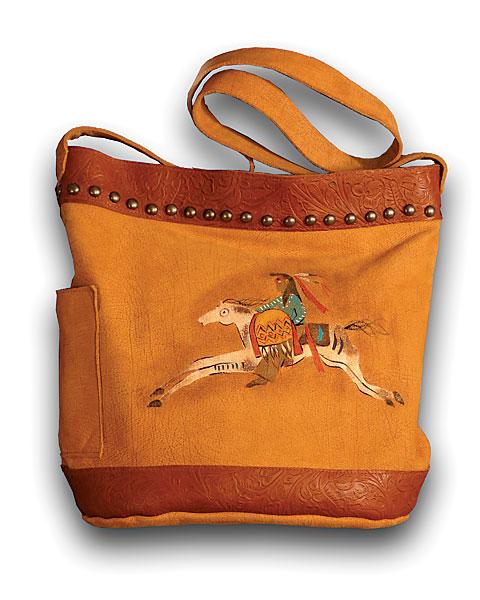

Whenever we want to see inspired design that pays homage to our American Indian culture, Patricia Wolf is one of the first designers we seek out. When it comes to her leather handbags, you’ll find a pallet of rich earth tones and designs that often mimic prehistoric hide paintings. Shown on these next five slides are some of our favorite native-inspired bags worth toting around. (Above) Made in tan aged cow with acorn tooled cow accents, this Bucket Bag is adorned with a hand painted Cayuse Pony & Rider; $346.

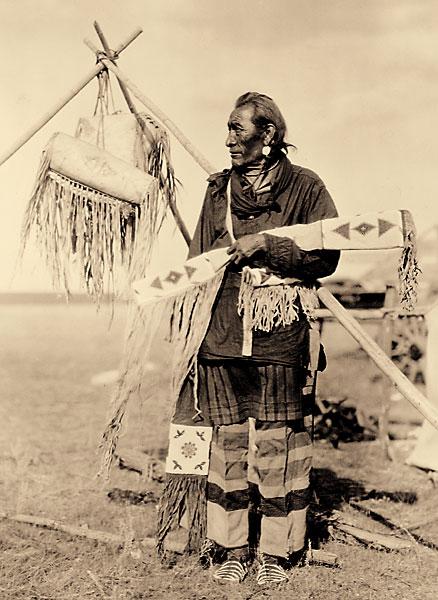

Four Piegan fringed leather medicine bags, hanging on a tripod, photographed by Edward S. Curtis in 1910.

–Historical images True West Archives; Fashion images courtesy Manufacturers–

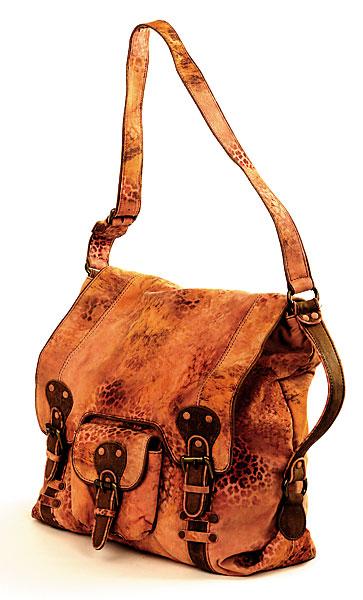

Founded in 1986, American West Leather Goods is known for its practical designs, authentic Western styling and handcrafted quality. Its collection includes more than 400 styles of purses, handbags, wallets, backpacks and luggage.

To commemorate the company’s landmark anniversary, American West is offering a limited edition 25th Anniversary collection of totes, shoulder bags and matching wallets. Each item will include a numbered tag and a 25th Anniversary silver keepsake.

Founder and designer Louise de Kok draws her inspirations from nearly every tradition and cultural touchstone the West has to offer, from primitive American Indian designs to flashy vaquero silver accents to classic cowboy tooling patterns. Her personal aesthetic infuses the products with a contemporary feel that ends up being stylish and timeless.

(Above) Diamonds are a geometric motif popularly seen in American Indian tribal design. The studded diamond border featured on the Victorian Parlour Collection from American West merges with leather hand tooling and cut-out accent patterns that are more reflective of Vaquero culture; The handbags and matching wallet retail from $78-$220.