“In all the top 10 lists of great cowboy actors, he’s never there, and it drives me crazy,” says Peter Ford of his father, Glenn.

“In all the top 10 lists of great cowboy actors, he’s never there, and it drives me crazy,” says Peter Ford of his father, Glenn.

The fact is, he’s right, and it’s hard to quite figure out why his dad, Glenn Ford, isn’t, and never really has been, held in the high regard he deserves.

One of the answers may lie in the fact that Glenn was at ease in every genre. People do remember him. He was listed among the top most popular actors several years running in the late 1950s, and he hit number one in 1958. But to his credit, and possibly to his detriment, when asked to name their favorite Glenn Ford movie, the answers are always different.

For crime and noir fans, the easy answer is The Big Heat, a tough police drama directed by Fritz Lang in 1953.

For fans of lighter romantic comedy, the answer is usually 1963’s The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, though he made several in that vein around the same time.

For people who love dark and flashy melodramas, loaded with high Hollywood glamour and a twisty sexual undertow, Gilda’s the one. So loaded was that 1946 picture that Hollywood reteamed Glenn and costar Rita Hayworth several more times, but the studios never got the lightning back into the bottle.

“I still don’t quite understand how they managed to get that one past the censors,” says Peter, who has just released a new biography of his father, Glenn Ford: A Life, “but people are still talking about it and taking it apart. It has a strong homoerotic element.”

The movie that had the greatest impact as a social drama was the king of all the juvenile delinquent pictures, Blackboard Jungle. Glenn played a decent Joe who’s trying to teach an urban classroom full of misfits, punks, crazies and killers. The 1955 movie put actor Vic Morrow on the map, but it made a star out of Sidney Poitier. It did something else for which Peter Ford takes complete credit.

“We were a pretty adventurous family when it came to music, and I was in the fifth grade and listening to a lot of Rhythm & Blues. I was crazy about the B-side of a new record by Bill Haley and His Comets. When director Richard Brooks was looking for music for the movie, dad brought him into my room,” Peter says. “That’s when I played him ‘Rock Around the Clock.’” The song became the opening theme of the movie and a national hit, and the first important Rock ’n’ Roll anthem.

But if there’s a single genre that can claim Glenn Ford, it’s the Western. “I think maybe a quarter of his pictures were Westerns,” Peter says. “For dad, making a Western was like taking a vacation. It was his bread and butter. He loved being out there and the camaraderie of the men.”

Glenn made more than 20 Westerns, beginning with Texas in 1941, a movie that costarred William Holden, who would be one of his lifelong friends.

He might have been drawn to making Westerns, because he was also a great horseman, Peter tells us. “He started out as a groomsman for Will Rogers while he was still in high school. He would go to Rogers’ ranch, where Clark Gable, Darryl Zanuck and all those stars kept their horses and played polo. When you see him in movies, on horseback, he glides; he’s just incredibly graceful.”

Yet Glenn learned the hard way to exercise caution. “He had an accident making The Man from the Alamo,” Peter says. “Victor Jory was in the film. Jory’s horse veered a little close, and dad’s horse veered into a tree. He broke three ribs, and he was out of the film for weeks. From then on, he was more cautious. It cost the studio a lot of money.”

The Man from the Alamo was directed by Budd Boetticher, who Western film fans will recognize as the director responsible for the great run of Randolph Scott pictures made in the 1950s. Boetticher and Glenn became friends, but one of the questions that haunts Glenn’s career is why he never teamed with any one great director long enough to create a body of work that would put him more visibly among his peers.

“He made only one movie with Budd Boetticher, and he made two terrific films with Lang,” Peter says, “but the one picture he made with William Wellman bombed. He never had the chance to work with a John Ford or a Howard Hawks or any of those guys. Imagine what he could have done in the hands of one of those directors?”

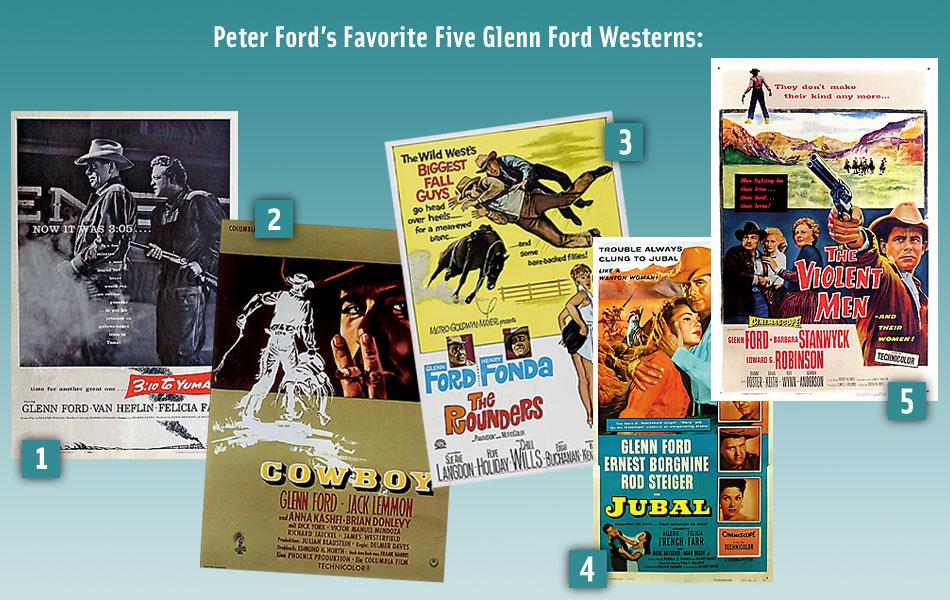

Glenn actually came close, though, with director Delmer Daves, who put him in three of Glenn’s best movies, and three of the finest Westerns of the 1950s, Jubal, 3:10 to Yuma and Cowboy. Of those three movies, 3:10 to Yuma has attained classic status; the lean and smart 1957 psychological drama is what critics used to label “good of its kind,” but the movie’s status grows with every new examination. So, too, are Jubal and Cowboy gaining respect. In between, The Fastest Gun Alive is developing a strong fan base.

The odd man out in the Ford Western canon is 1958’s The Sheepman, a strangely written, semi-comedic picture that costarred Shirley MacLaine. “That’s one I can’t understand,” Peter admits, “but it has legions of fans who think it’s the best thing my dad ever did.”

Peter’s book is something of a curiosity as a biography, because not only is it an intimate portrait of his father, but it’s also Peter’s own story.

He doesn’t hesitate to describe his own difficult childhood. “My dad is a very, very fine underrated actor, and I wanted to honor him. But I also wanted to tell the story of him not really having the capacity to be a dad,” Peter says.

The biography is also unlike most in that it benefits from Glenn’s own extensive diaries, his lengthy conversations with his son and a wealth of personal tapes. “He’d sit by the pool with a tape recorder, when he got older and had time on his hands,” Peter says. “I have hundreds of tapes—thank god he labeled most of them. He’d sit there and talk about himself, about his films and the directors, of friends and costars like William Holden, and of the women he knew.”

This can’t be stated too strongly: a lot of women played a part in Glenn’s life, and a lot of women are featured in his son Peter’s book. As Peter explains it, “I think I counted something like 143 or 146 women who pass through my dad’s narrative. And any movie fan will recognize 90 percent of them.”

Peter has been, at various times, an actor, a recording artist and a businessman. What’s interesting about his relationship with his father, the Canadian-born son of a train engineer who became an international movie star, is that Peter admires his father’s talent, respects his work ethic and his devotion to craft, and wishes he’d been a better dad. And he loves his movies.

“The Big Heat, 3:10 to Yuma and Blackboard Jungle—that’s the trifecta to me,” he says. “For my dad, though, I think that, of the Westerns, and really, all his movies, I know he had a wonderful time in a picture that was not given a lot of attention, The Rounders, with Henry Fonda. My dad and Henry were both disappointed by how [the studio] marketed that film. I think they put that at the bottom of a double bill with Get Yourself a College Girl,” Peter says with a laugh. “But it was a shame, and he was rueful about the fact that [the movie] didn’t get a better break.

“I think that 3:10 to Yuma is something that he took a lot of pride in. John Barrymore once told him to never pass up a chance to play a villain. I think he remembered that when he took on 3:10 to Yuma.

“I was very upset when they remade it. It’s such a subtle film. You don’t need a guy with a peg leg and all that stuff. Here’s a rancher whose wife wanted him to stand up and be a man. It was simple.

“A lot of people at the time thought the ending was contrived, but I could see how my father could jump up on the train. According to my father, his character identified with Van Heflin’s, and he felt that Van needed to be the man; that he had a family…. he had everything that my father didn’t have. My father’s character wanted to enable Van to go home to this woman having proven something, to come home a hero. It was a very generous gesture, on the part of my father’s character.

“Dad loved Westerns and he made some really good ones. Even to this day, I have thousands of people, thousands of fans, who I correspond with, in France, Brazil, Japan, Chile, all over the world,” Peter says. “He never gave a poor performance, and the fans loved him.”

Photo Gallery

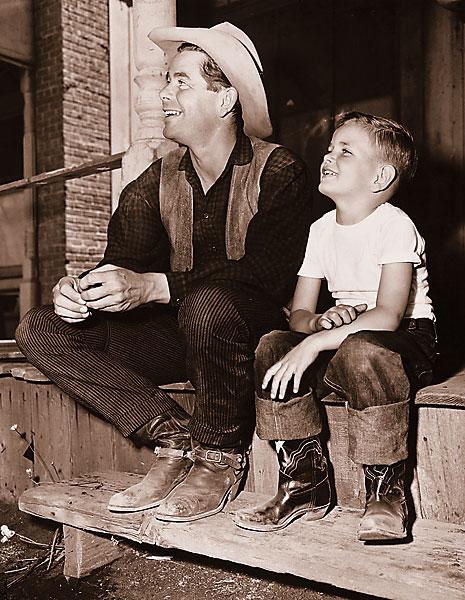

—Peter Ford, shown with his famous actor father, Glenn.

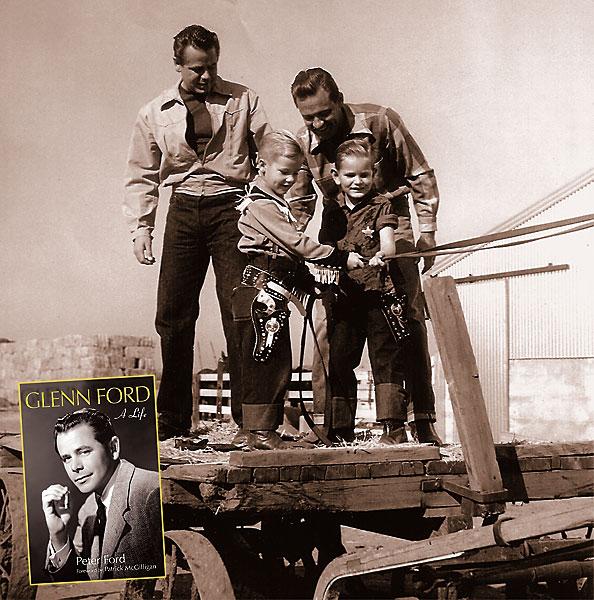

In his autobiography of his father, Glenn Ford, Peter shares numerous family photos, including this photo of an outing to the Hudkins Bros. Movie Ranch in Burbank, California. Peter stands in front of his father, on the left. Next to them is William Holden and his son, also named Peter. Glenn starred in two Westerns with the elder Holden: 1941’s Texas and 1948’s The Man from Colorado. Of this photo, Peter tells us: “Ace Hudkins was a friend of my dad’s and owned the ranch. The ranch has since been torn down and is now the famed Forest Lawn Cemetery.”

– Courtesy Peter Ford, from Glenn Ford: A Life, available at GlennFordBio.com –