Standing in front of the gallows at Fort Smith National Historic Site, I’m overcome by history.

Standing in front of the gallows at Fort Smith National Historic Site, I’m overcome by history.

Just up those steps, the Dalton brothers became “just a little bit dead” after they were “hung.”

I know that because that’s what John Wayne tells Michael Anderson Jr. in The Sons of Katie Elder. Maybe that’s my problem. I get too much history from movies.

Perhaps the Duke was wrong, and the Daltons weren’t hanged. After all, Randolph Scott watched the brothers shot to pieces in When the Daltons Rode. And the dirty little coward Robert Ford and Jesse James’s “adopted” son helped wipe out the gang during Jesse James vs. The Daltons. After the fiasco in Coffeyville, Kansas, Judge Isaac Parker shot down a sneaky railroad dick—because Dale Robertson and Jack Palance wouldn’t do anything historically inaccurate in The Last Ride of the Dalton Gang.

Yeah, it’s time to learn what really happened.

The best place to start is Fort Smith, that legendary “bastion of law and order” where “Hanging Judge” Isaac C. Parker presided over the Federal Court for the Western District of Arkansas for more than 20 years. Nope, the Daltons didn’t wind up on these gallows, but 79 others got their necks stretched here.

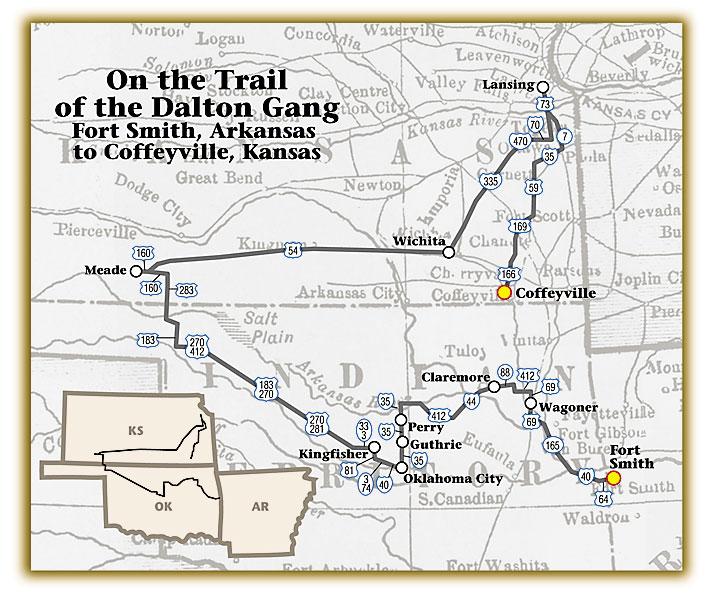

Sure, Emmett, Frank, Grat, Bob and Bill—five of Lewis and Adeline Dalton’s 15 kids—were born in Missouri, but I’m starting the Dalton trail in Arkansas. Brother Frank pinned on a badge for Judge Parker’s court in 1884. On November 27, 1887, Frank and Deputy U.S. Marshal James Cole went to arrest Dave Smith for larceny and introducing and selling whiskey in the Indian Nations. Smith had company, and they put up a fight. In the end, Frank Dalton, Dave Smith and a woman named Jennie Dixon were dead; Cole was wounded; and the law was after Frank’s killers.

Why doesn’t Hollywood film that story?

Grat and Bob tried filling Frank’s boots as deputy marshals, working out of Fort Smith and Wichita, Kansas—brother Emmett sometimes rode with them in posses. Trouble was, they seemed better suited on the other side of the law. Grat was once charged with horse stealing, and Bob with introducing whiskey into the Nations.

By 1891, the brothers were in California, accused of robbing a Southern Pacific train at Alila. But talk about criminal! Have you seen what gas prices are today? Let’s stay clear of Fresno and keep this road trip to Oklahoma and Kansas.

Like the more successful James-Younger Gang (Ma Dalton was Cole, Bob and Jim Younger’s aunt), the Dalton outfit varied from crime to crime: “Black-Faced” Charley Bryant, “Bitter Creek” George Newcomb, “Cockeye Charley” Pierce, “Narrow-Gauge” Bill McElhanie, Too-Good-To-Have-NicknamesBill Doolin and Dick Broadwell, and Bob’s alleged lover, horse thief Flo Quick, alias Eugenia (maybe), alias Tom King.

Their Specialty was Trains

The Santa Fe went down in Wharton (near present-day Perry, Oklahoma) on May 9, 1891. On September 15, the gang hit the Missouri, Kansas and Texas near Wagoner. A holdup of the Santa Fe came at Red Rock on June 1, 1892. Then the Daltons robbed the Katy at Adair on July 14, 1892.

The latter didn’t go so well. Guards cut loose with Winchesters. As the outlaws escaped through Adair, W.L. Goff and T.S. Youngblood were wounded, Goff mortally. Historian Robert Barr Smith writes: “Now there was a rough protocol even among western outlaws, and part of it was that you didn’t shoot preachers and you didn’t shoot doctors.” Youngblood and Goff were sawbones.

The Katy put up a $5,000 reward. The Fort Smith court issued murder warrants. Everybody was after the Daltons.

Tracking the Daltons in Oklahoma today is as troubling as it was for marshals in the 1890s. You just won’t find much. Even the 91-year-old steam locomotive in Adair has left the park, sold off to a North Carolina museum this summer. But you can still buy wild game and Indian crafts at Adair’s Twin Arrows Buffalo Market, or shop for pecans at the Crooked Little House Pecan Orchards. You can hike or fish at Adair State Park. If you’re looking for history, head to Colcord and stop at the nonprofit Talbot Research Library & Museum. The library is used mostly by genealogists, but the two-acre complex also includes old buildings, farm machinery and a 1920s-era one-room schoolhouse.

Claremore remembers Will Rogers (and rightfully so) more than the Daltons, but after you check out the Will Rogers Memorial Museum, make sure to visit the J.M. Davis Arms & Historical Museum. Billed as the world’s largest privately owned gun museum, it exhibits firearms, swords, knives—even 1,200 steins—as well as a “Believe It or Not Oddities Gallery.” It also houses a score of outlaw weapons, including Emmett Dalton’s .45-caliber Colt.

To relive the 1890s Cherokee Strip rush, head to Perry and take a walking tour along the plaza or visit the Cherokee Strip Museum & Rose Hill School.

The Chisholm Trail Museum in Kingfisher houses a log cabin that belonged to Ma Dalton and shares a lot of information about cowboying.

The best cities to learn about 1890s Oklahoma are probably Oklahoma City and Guthrie.

The Daltons reportedly did hide out around Guthrie, and Oklahoma’s first capital is a great town to visit, whether you’re trailing the Daltons or not. Start off at the Oklahoma Territorial Museum, housed in a historic Carnegie library. Then choose your pleasure:

State Capital Publishing Museum (the press wasn’t kind to the Daltons), Oklahoma Frontier Drugstore Museum & the Apothecary Garden (Emmett Dalton would soon need a lot of drugs), the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame Museum (Grat Dalton would soon wish he were shooting hoops for the Oklahoma City Thunder), the Guthrie Scottish Rite Masonic Center (Bill Dalton might not have been a Mason, but his real name was Mason Frakes Dalton) and the Owens Arts Place Museum (Bob Dalton would soon wish he had taken up oil-on-canvas).

Down in Oklahoma City, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum is a Western treasure, and the Oklahoma History Center is equally wonderful. Nor can you beat hanging out at the historic stockyards; I know that Belle Starr, Jesse and Frank James, Cole Younger and two Dalton boys tried to rob the stockyards.

That’s what happens in Belle Starr, a 1980 CBS movie with Elizabeth Montgomery. Oh, no. That was Tulsa, not Oklahoma City. My mistake. But visit OKC’s stockyards anyway.

Tracking the Daltons in Kansas

To really learn about the Daltons, you need to go to Kansas. So I make my way to Meade.

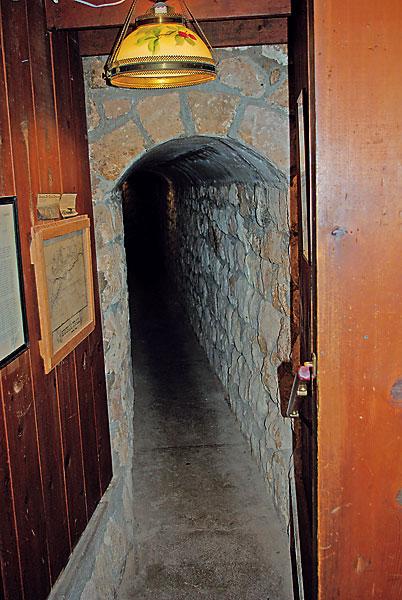

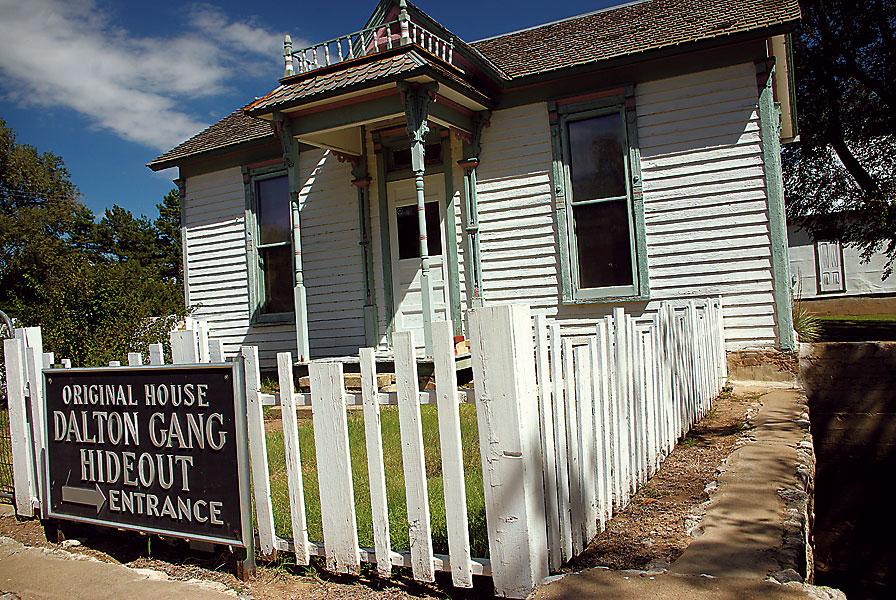

All right, some historians believe the Dalton Gang Hideout is as historically sound as the 1949 movie The Dalton Gang. Even manager Marc Ferguson points out, “Whether the gang used

it or not is a matter of speculation.” But the house was owned by Eva Dalton Whipple, the brothers’ sister, and it was built in 1887. Years later, a 95-foot-long tunnel was found leading from the house to the barn; legend grew that the Dalton Gang used the tunnel.

By 1939, the original tunnel had collapsed, so the WPA National Youth Administration reconstructed it, the Meade Chamber of Commerce bought the property, a park was completed by 1942 and the Dalton Gang Hideout has been bringing in tourists ever since.

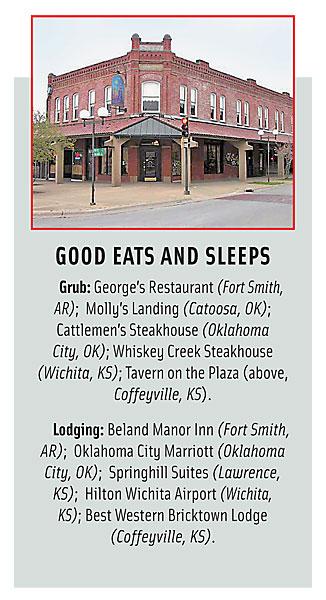

Since the Daltons worked as peace officers out of Wichita, I figure that’s a good place to stop. Hey, I’ll find any reason to visit Old Cowtown, an excellent living history museum the city took over in 2007. The town’s old buildings are still great, and a new exhibit gallery makes Old Cowtown even better. “It’s like walking back in time from the beginning,” my guide tells me.

Cruising to Coffeyville

It’s time to get to the end of this Renegade Road, so, with a quick detour to Lansing, I drive down to Coffeyville.

On the morning of October 5, 1892, the Daltons and pals rode into Coffeyville planning to rob two banks—the First National and the Condon—simultaneously.

Since some of the hitching posts had been removed while the streets were being modernized, the outlaws tied their horses along a fence in a narrow passage, 130 yards from the Condon and 170 from the First National. Grat, Power and Broadwell went into the Condon. Emmett and Bob took the First National. They may have worn theatrical facial hair, but those disguises didn’t fool the citizens. The boys were recognized.

Isham’s Hardware—still in business today—faced the Condon, and weapons were passed out among citizens in the shop. Shooting started—roughly 200 shots in 12 minutes.

In the end, Bob, Grat and Power were dead in “Death Alley.” Broadwell rode about a half-mile before he keeled over dead. Emmett, who tried to save dying (or dead) brother Bob before getting shot out of the saddle, would spend nearly 14-and-a-half years in the prison at Lansing (also still in business and home to

a small, but neat, museum). Four town defenders—including Marshal C.T. Connelly—would be killed, and three others wounded. (FYI: marshals would cash in Bill Dalton’s chips in June 1894 at his home near Ardmore, Oklahoma.)

The First National moved in 1953, but Coffeyville really hasn’t changed much. The Perkins Building, the Condon’s home in 1892, has been restored, with markers to show where defenders and outlaws fell. The old jail was moved,

rock by rock, to Death Alley, where a recording tells the story of the raid. The Dalton Defenders Museum is a great place to learn the facts of the raid.

Bob, Grat and Power wound up at Elmwood Cemetery. So did Broadwell, although his body was exhumed and reburied at a family plot in Hutchinson. I make my way to Elmwood. The sign erroneously states that the dead outlaws’ grave was marked with a hitching rail from Death Alley (see

p. 15). The names have been chipped away on the granite marker.

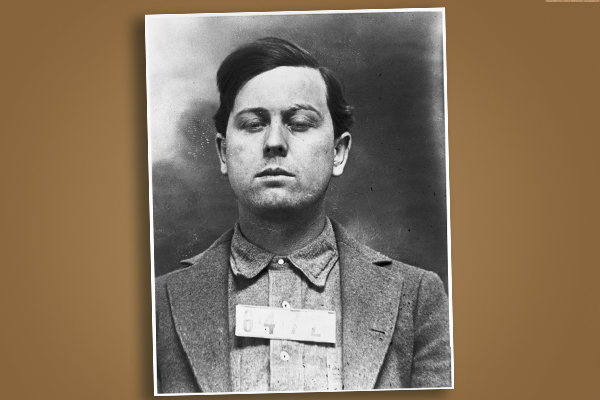

A few yards away, I find the grave of another Dalton brother. The final resting place of Deputy U.S. Marshal Frank Dalton, killed in the line of duty, doesn’t get as much traffic as his brothers’ grave.

That’s a shame, I think, because of all the Dalton brothers, he’s the one we really should remember.

Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite Dalton movie might be The Dalton Girls, while his favorite Dalton novel is Ron Hansen’s Desperadoes.

Photo Gallery

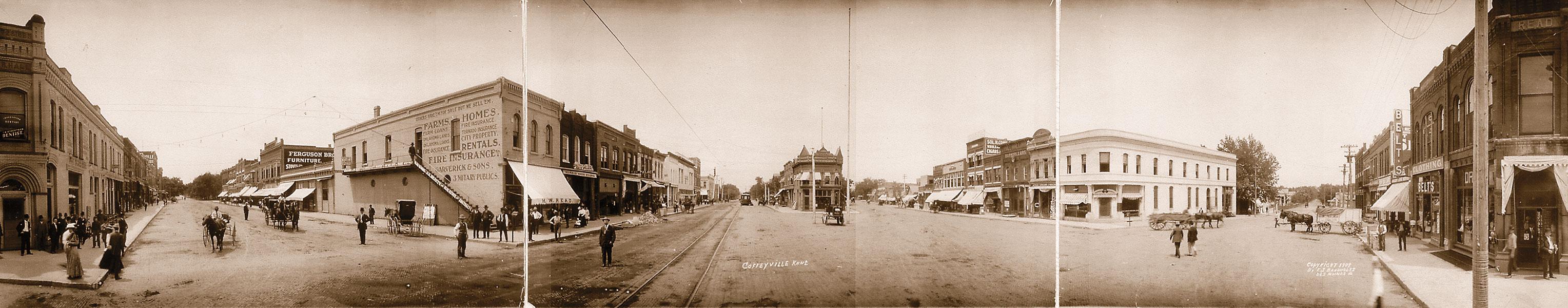

This panorama of Coffeyville, Kansas, was taken 17 years after the Dalton Raid. Although the First National Bank burned down years ago, the C.M. Condon & Co. bank is still in business (although in another location); another business still welcoming customers is Isham’s hardware store, where some Coffeyville citizens holed up and shot at the gang.

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

– Frank Dalton photo courtesy Fort Smith National Historic Site –