On May 28, 1868, during a U.S. Congress floor debate about an Indian appropriation bill, Montana Territory representative James M. Cavanaugh remarked, “…I

On May 28, 1868, during a U.S. Congress floor debate about an Indian appropriation bill, Montana Territory representative James M. Cavanaugh remarked, “…I

will say that I like an Indian better dead than living.”

On October 27, 1895, The New York Times reminded its readers, “Even in this day of [the] increasing civilization of the Indian race there remain many intelligent persons who still believe that ‘the only good Indian is the dead Indian.’”

Supposedly uttered in January 1869, the latter part of the above quote is perhaps a paraphrased version of the Cavanaugh remark. This vituperation has been attributed to Gen. Philip H. Sheridan shortly after November 27, 1868, when Lt. Col. George A. Custer fought against the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes at the Battle of Washita River in what is now western Oklahoma.

Given many Americans’ prevailing attitude of homicidal prejudice against American Indians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, history books do not overflow with the biographies of Indians who were celebrated in matters other than resistance to the onslaught of white civilization.

Yet in the same 1895 column, after quoting Sheridan’s invective, the Times praised one man whose “…life and work…are a most convincing proof of the fallacy of this once popular belief.”

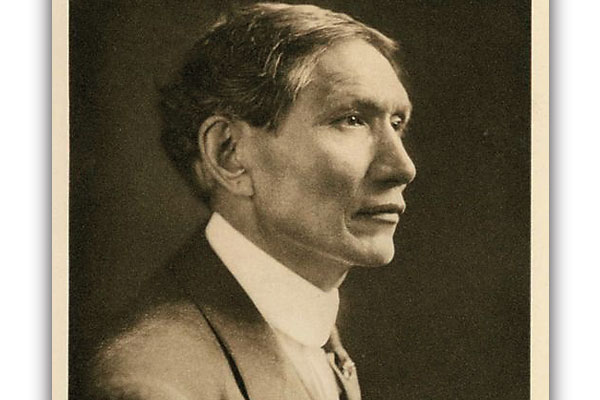

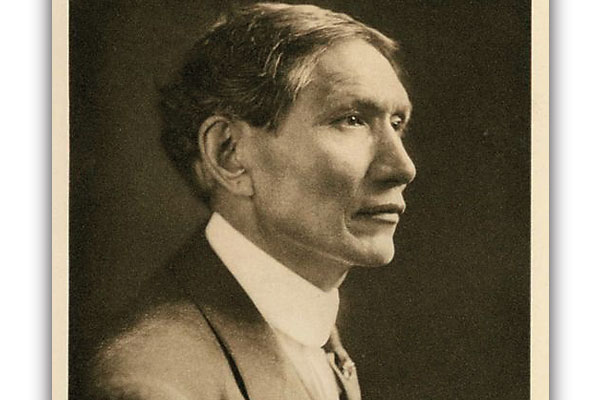

This exception was a Sioux man (three-quarters by blood), probably born in 1858, just weeks before Minnesota was admitted to the Union. He was first named Hakadah, the “pitiful last,” because he was the youngest of three brothers and one sister. In his early youth he was re-named Ohiyesa, the “winner, or one who wins often,” after demonstrating what was to become lifelong athletic prowess.

Fleeing the Sioux uprising with his grandmother in 1862, Ohiyesa spent the first 15 years of his life raised by his grandmother and his uncle, in the traditional manner of a young Sioux brave. His father, Many Lightnings, a full-blooded Sioux pardoned by President Lincoln after the 1862 uprising, adopted white customs, became a Christian and was reunited with Ohiyesa in about 1873.

As the Times column revealed, Ohiyesa’s childhood was anything but simple. After rejoining his father, “[Ohiyesa] was put in school, but never having been accustomed to confinement, he thought he was going to smother.” Many Lightnings was determined that his son become educated, and he succeeded brilliantly.

Overcoming his initial ambivalence and trepidation, Ohiyesa embraced the white man’s education with great passion. He not only graduated from medical school in Boston, he was also class orator. His first medical position, in 1890, was working as the government physician for the Sioux at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Throughout his lifetime, Ohiyesa wrote 11 books, established 32 Indian chapters of the YMCA and helped found the Boy Scouts of America and the Campfire Girls.

When he became a Christian, Ohiyesa adopted the name Charles Alexander Eastman, preserving the last name of his maternal grandfather, who had been a soldier in the U.S. Army. Both Dr. Eastman and his soon-to-be bride, Elaine Goodale, a superintendent of Indian Education for the two Dakotas, cared for survivors the day after the Wounded Knee Massacre at Pine Ridge on December 29, 1890.

Dr. Eastman’s current fame has been cinematically boosted by Adam Beach’s portrayal of him in HBO’s 2007 movie Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Beach earned a Golden Globe nomination for his performance.

Ohiyesa is a man with whom I have a minor but not unimportant collegial bond. I completed medical school on the same campus where he completed his undergraduate work, 89 years earlier. I nostalgically refer to Hanover, New Hampshire, and the campus of Dartmouth College, a school founded in 1769, with a mission to educate Indian students.

I treasure this small connection with Dr. Eastman. I cannot fathom how this man, this fellow physician, overcame such monumental obstacles. Compared to him, I have had a fairly easy row to hoe.

Dr. Jim Kornberg holds an MD and an ScD. He is an environmental medicine physician and an engineer. He lives with his wife Sally on their ranch in the mountains of southwestern Colorado.