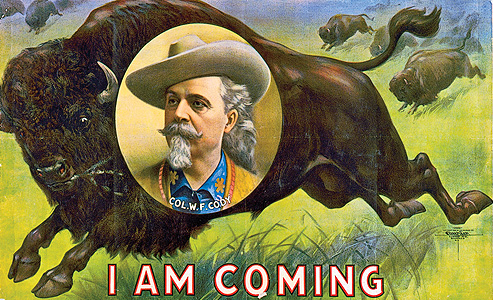

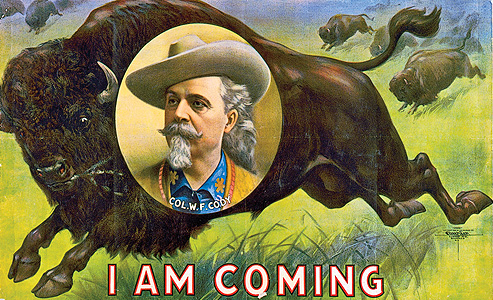

Buffalo Bill Cody was one of a handful of civilian scouts ever awarded the Medal of Honor for courage in battle. Yet his mettle would be tested many years later by a man who drafted blueprints and knew nothing of warfare on the Western plains. Cody often thought it was the finest performance of his life.

Buffalo Bill Cody was one of a handful of civilian scouts ever awarded the Medal of Honor for courage in battle. Yet his mettle would be tested many years later by a man who drafted blueprints and knew nothing of warfare on the Western plains. Cody often thought it was the finest performance of his life.

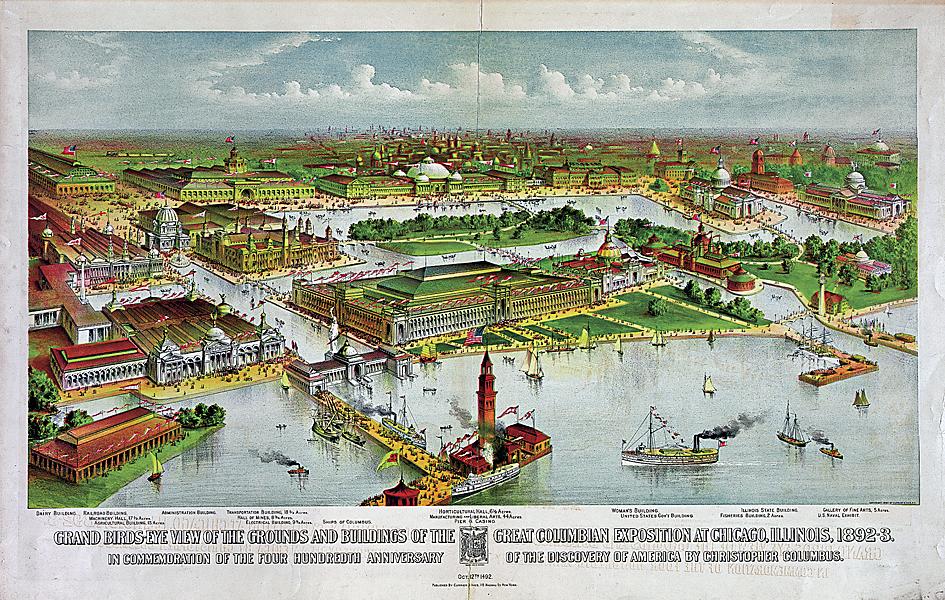

Daniel H. Burnham, the foremost architect in Chicago, Illinois, was appointed the director of works for the 1893 world’s fair. The official name of the fair, the World’s Columbian Exposition, commemorated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. Upon his selection, Burnham wrote a prophetic entry in his daily journal: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood….”

Indeed, from the outset, Burnham’s goal was to stir men’s blood. His mission, assigned to him by fair organizers and Congress, was to surpass the marvels of the Exposition Universelle produced by France and held in Paris in 1889. Acclaimed the world over, the fair had been so majestic and exotic that no one thought it could ever be equaled. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, a French engineer, created the grandest spectacle of all.

The Eiffel Tower soared into the sky. More than 1,000 feet in height, it was the tallest man-made structure in the world, a feat of extraordinary ingenuity. America’s pride as an international power demanded a response, something to eclipse the French exposition and its Eiffel Tower. The World’s Columbian Exposition was the answer, and four cities—New York, Washington, D.C., St. Louis and Chicago—submitted bids. After several rounds of intense lobbying, Congress awarded the charter to Chicago. Burnham spent more than $22 million (almost $600 million in today’s dollars) to make it happen.

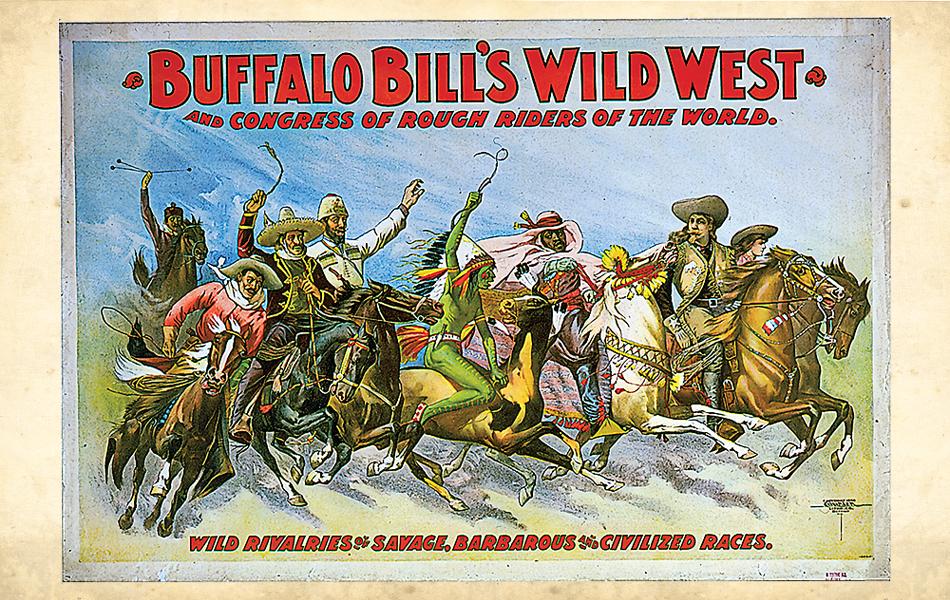

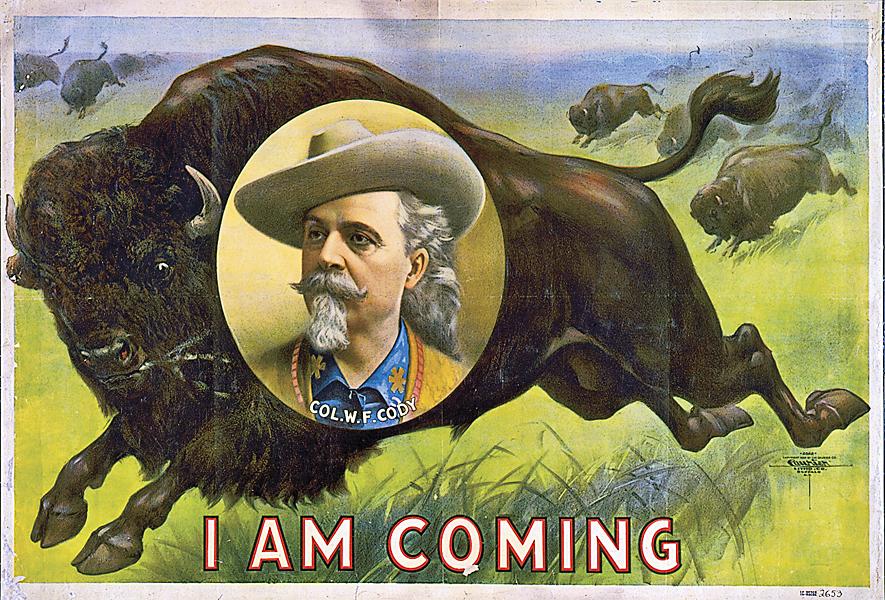

Cody, from his ranch in Nebraska, immediately grasped opportunity in the Columbian exposition. His “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World” show had recently returned from a hugely successful tour of Europe. Ever alert to profitable ventures, he foresaw fortune awaiting at the world’s fair. He promptly dispatched his partner and business manager, Nate Salsbury, to Chicago.

The exposition’s Committee of Ways and Means was the governing body for all concessions at the fair. Salsbury made an enthusiastic pitch, extolling the wonders of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West extravaganza. After due consideration, the committee informed Salsbury that the tariff for a concession was 50 percent of gross proceeds—not profits, but 50 cents of every dollar collected for admission.

When Salsbury returned to Nebraska, we can only imagine Cody’s reaction. Quite probably he shouted something on the order of: “Fifty percent! Who do those S.O.B.s think they are?”

Within a short time, he would learn not just who they were, but more important, the grandeur of their plans. The Columbian exposition was envisioned as the most spectacular attraction in the world.

Burnham had hired a brigade of the most eminent architects, engineers and contractors in America. The fair would cover roughly one square mile, with more than 200 newly constructed buildings and 57 miles of roadways, along the Jackson Park shoreline of Lake Michigan, with the main buildings on a network of lagoons extending inland. The Midway alone was a mile long, and one structure, the Manufactures and Liberal Arts building, would occupy nearly 32 acres.

Designed to thrill and titillate, the attractions were drawn from around the globe. Great Britain would display a model of its latest warship, the Victoria. Germany would showcase the largest artillery piece ever made, firing a one-ton shell. Japan would host an immense outdoor exhibit of its unique Buddhist temple. Egypt’s “Streets of Cairo” would present half-clad women in the danse du ventre, the famous belly dance. Attendees would walk through a Moorish palace, an Algerian Village and pavilions from Canada, Norway and Russia.

Along the lagoons and roadways, a wooded island would be created out of trees and willow cuttings and other landscape beauties. Theodore Baur’s bronze sphinx, mummified remains, Africa’s supposed “cannibal tribe” and a battalion of Syrian horsemen would be displayed. Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope would screen the first moving pictures; the first-ever all-electric kitchen would be exhibited; the living Aunt Jemima would make her debut, marketing a pancake mix; and legend claims two brothers would sell (most likely outside the gates) a molasses-coated popcorn and peanut concoction that later became known as Cracker Jacks. Contractors would employ upwards of 20,000 workmen to transform Burnham’s vision into reality.

Every building in the exposition compound was painted a soft shade of white, creating a luminous brilliance under the arc of searchlights that played over the grounds at night. A clever wordsmith at the Chicago Tribune promptly enshrined it for the world as the “White City.”

For all that, Cody was not one to be denied. The exposition was scheduled to run six months, May 1 to October 30, and he meant to be there—without handing over 50 percent of his gate receipts. He dispatched Salsbury once again to Chicago, where the manager leased about 15 acres of land adjacent to Jackson Park.

On March 20, a long train carrying the Wild West show arrived at the rail yards. Unloaded from the cars were 100 former cavalry troopers, 46 cowboys, 97 Cheyenne and Sioux Indians, 53 Cossacks and Hussars, and several herds of animals, including horses, buffalo and elk. America’s darling sharpshooter, Annie Oakley, was greeted by a mob of newspaper reporters.

In a game of one-upmanship, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World opened on April 3, four weeks before the exposition. The show presented bronc busters and wild animals, a cowboy band tooting popular tunes, a choreographed Indian attack on the Deadwood stagecoach (vanquished by mounted troopers) and a realistic staging of “Custer’s Last Stand.” In daring feats of marksmanship, Oakley blasted an impossible array of targets, and Cody, on horseback, shattered glass balls thrown into the air. On some days, every seat in the 18,000-seat arena was sold out.

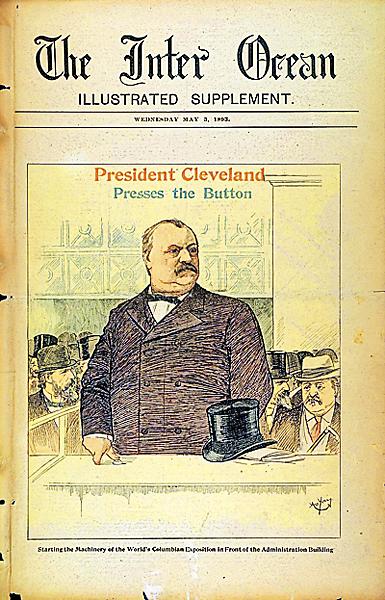

Burnham was understandably outraged. But on May 1, with great fanfare, the World’s Columbian Exposition staged its grand opening. President Grover Cleveland led the procession into the fairgrounds, followed by carriages occupied by assorted dignitaries from America and a host of foreign countries. Behind them were around 150,000 Chicagoans, on foot and jammed into omnibuses and streetcars. The approaching crowd was greeted by 1,500 members of the Columbian Guard, attired in blue uniforms, white gloves and black capes. Attendance on the fair’s best day, Chicago Day, was 761,942 people, which beat out the best day, by almost half, at the

Paris exposition.

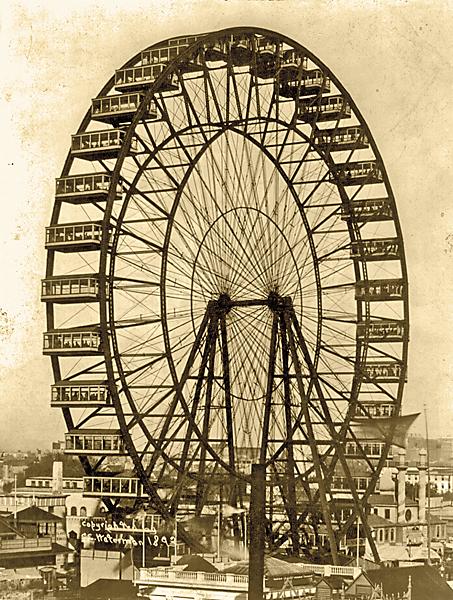

At the center of the Midway was America’s response to the Eiffel Tower. George Ferris, an engineer from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had constructed a gigantic wheel 264 feet in diameter and 264 feet high. Quickly dubbed the “Ferris Wheel,” it revolved in circular motion with 36 cars, each holding 60 people, for a total capacity of 2,160 passengers. Powered by twin thousand-horsepower engines, with an assemblage of 100,000 parts, the wheel weighed more than 2.4 million pounds when filled to capacity. Dominating the Midway, illuminated by thousands of brilliant lights, the ferris wheel was visible from miles away. French dignitaries attending the fair reluctantly conceded that it was the “engineering marvel of the age.”

Nonetheless, Cody often upstaged the exposition. On one occasion, fair officials refused a request by Mayor Carter Harrison that the poor children of Chicago be admitted for one day at no charge. Ever the consummate showman, Cody immediately announced a “Waif’s Day” at the Wild West. He offered every child from Chicago free train tickets, free admission to his show and free access to roam the Wild West encampment. To top it off, he also gave them all the candy and ice cream they could eat, free of charge. Fifteen thousand children swarmed the Wild West, and Cody was hailed as a “champion of the poor.”

After a dazzling six-month run, the World’s Columbian Exposition closed on October 30. To commemorate the occasion, full-sized replicas of the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria sailed across Lake Michigan and landed at Jackson Park. Actors playing the parts of Columbus and the various ships’ crews clambered ashore in authentic costumes and claimed the New World for Spain. The following day, fair officials paid off the last of the $22 million grant used to fund the exposition.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World closed a day later. During its engagement, an average of 16,000 spectators attended each of the 318 performances, for an overall attendance exceeding five million. Cody cleared about a million dollars in profit (nearly $30 million today). He used part of the proceeds to found his namesake town, Cody, Wyoming; build an extensive fairgrounds for North Platte, Nebraska; and retire the debts of five Nebraska churches. The balance went toward expanding the panorama of his Wild West extravaganza.

In the end, Cody departed Chicago with a million in cash and the irony of the last laugh. He never paid a red cent to Burnham or the World’s Columbian Exposition.

The recipient of Western Writers of America’s Owen Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement in Western Literature, Matt Braun has written nearly 60 novels and books, with more than 40 million copies in print.

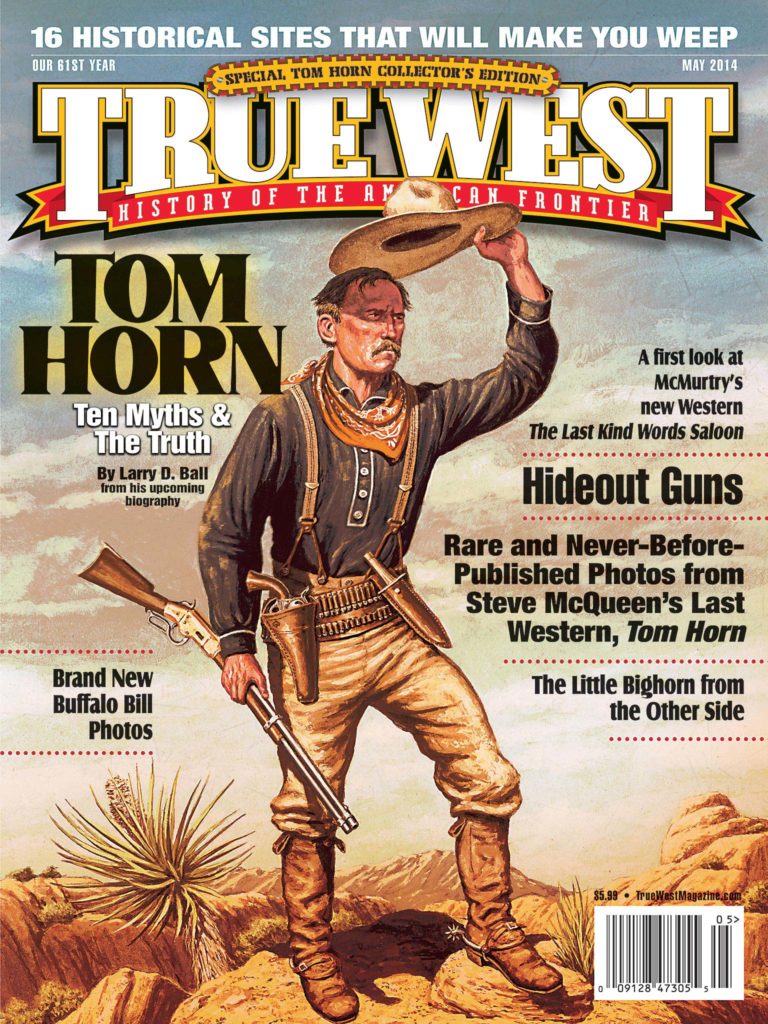

Photo Gallery

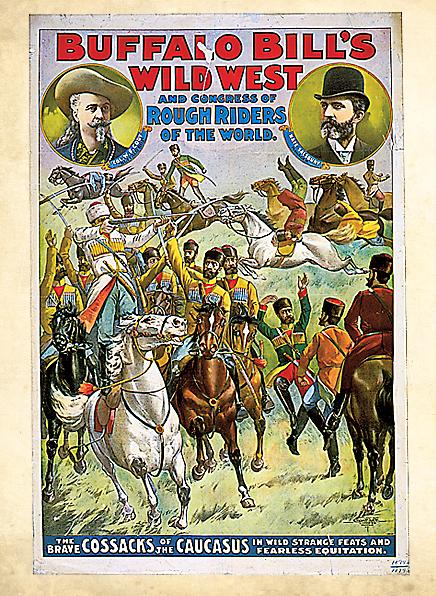

After Wounded Knee, Cody was not sure if he would be allowed to hire Indians again for his Wild West show. So he and Nate Salsbury began seeking out other racial primitives, such as Russian Cossacks and Argentine gauchos. They found a great success with these additions in their tour of Europe, and thus they renamed the show “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World,” just in time for the 1893 world’s fair in Chicago.

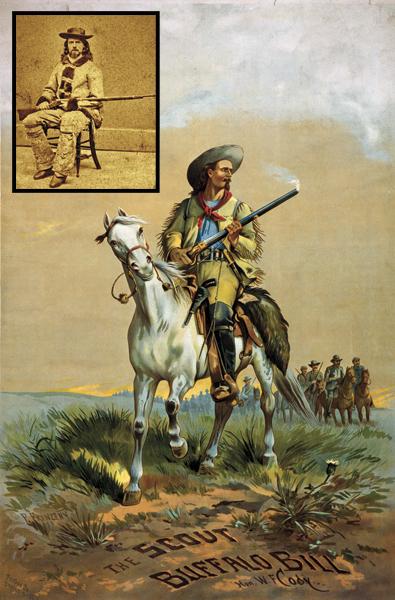

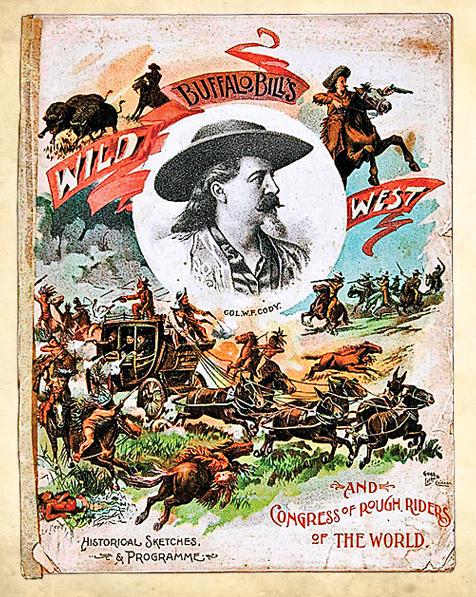

The 1893 program printed by Blakely Printing Company of Chicago featured biographical sketches of Cody and cast, as well as a history of the Wild West show.

– All images courtesy library of congress unless otherwise noted –