The only market that Texans can rely on at present for their stock is Bakster [sic] Springs, Kansas …” a Texas drover wrote from present-day Oklahoma back in 1867.

The only market that Texans can rely on at present for their stock is Bakster [sic] Springs, Kansas …” a Texas drover wrote from present-day Oklahoma back in 1867.

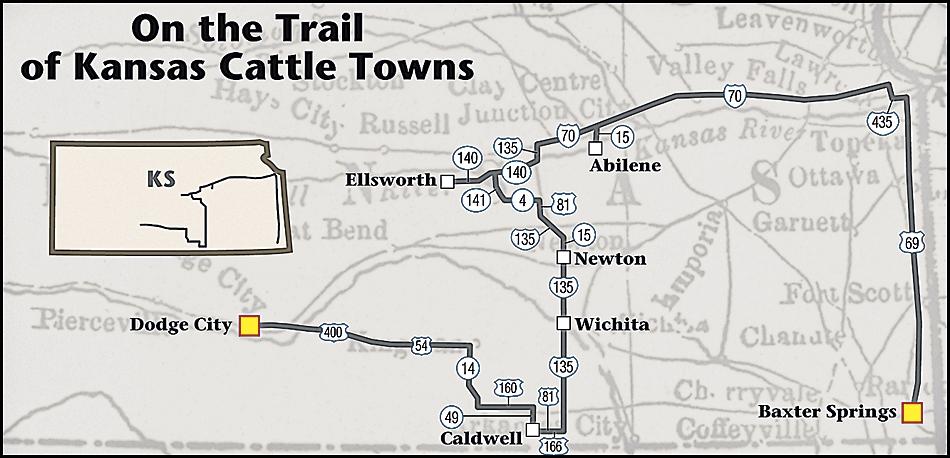

Bakster? Yeah, even back in 1867, Baxter Springs didn’t get much respect as a cattle town. “The First Cowtown in Kansas” reportedly opened for Texas Longhorn business as far back as 1866. By 1872, Baxter Springs was just a memory to Texas cattlemen and cowboys.

And today?

That’s my question on this journey. Which Kansas cowtowns still promote that wild and woolly heritage? So I drop by the Baxter Springs Historical Center & Museum to meet historian Larry O’Neal and get a tour of the town.

Once, gold and silver were exchanged—no currency, since Texans were apprehensive about greenbacks—for Texas beef, and Baxter Springs boomed. But these days, the local economy is suffering, and many citizens and businesses promote Baxter Springs as something other than a cattle town. I guess they’re getting their kicks on Route 66. “Only 13.2 miles of Route 66 pass through Kansas,” O’Neal says, and Baxter’s the biggest of the three Kansas communities the Mother Road motors through.

And history buffs? These days, what interests them is the Civil War. The museum sits on the spot where William Quantrill lined up his men to attack Fort Blair in 1863. The Massacre of Baxter Springs—“the zenith of Quantrill’s career”—followed.

Regarding the cattle days, artifacts are exhibited at the museum, and the land where the cattle grazed hasn’t changed much. But hay, lead, zinc and baseball replaced cattle (the New York Yankees found Mickey Mantle playing here for the semi-pro Whiz Kids in the late 1940s).

“Our heritage goes back a long time,” O’Neal says. “I think we need to accentuate [the cattle days] more. How do we do that? Quite frankly, I don’t know.”

Abilene: “The Wickedest and Wildest”

What I’ll hear at practically every cowtown is this: “After the cowboys left, most towns wanted to forget about that part of their history.”

I’m eating lunch with Jeff Sheets, historian for the Heritage Center of Dickinson County in Abilene, the town that Joseph McCoy helped turn into one of the quintessential cowtowns. What had started as a small prairie village in 1861 was booming with cowboys, cattle buyers, gamblers, gunmen and prostitutes by 1868, but after 1871, Abilene’s reign had ended.

Yet, while many cowtowns faded into ghost towns or forgotten small towns, Abilene boasts a population of roughly 6,700 and visitors galore.

“It didn’t hurt,” Sheets says, “to have a president living here.”

Having the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home is important, but Abilene isn’t sweeping its cowboy dirt under the rug.

You can get your history at the Heritage Center (and take a ride on the circa 1901 C.W. Parker Carousel). Then head over to Old Abilene Town for gunfights, can-can girls and sarsaparilla. “It’s entertainment,” Sheets says, “not historic.”

The Abilene and Smoky Valley Railroad operates seasonal excursion and dinner rides, and the American Indian Art Center shows another side of Abilene’s Western heritage.

Ellsworth: “Wickedest Cattle Town in Kansas”

From Abilene, Jim Gray, Ellsworth’s resident historian known as “The Cowboy,” advises me to take “the old 40 highway” (now State Highway 140) to Ellsworth. Smart people know that they should listen to Gray.

“You are traveling through CK Ranch country,” Gray tells me. “Top Hereford cattle since the 1940s. Old 40 is right on the Smoky Hill Trail. The 140-141 intersection is classic Smoky Hills rangeland.”

When I meet him for an early supper, Gray says, “Grass and cattle are still a major part of the Ellsworth experience. I think that’s what separates Ellsworth from Kansas’s other cattle towns.”

That, and the fact that most cowtowns don’t have someone as passionate about Western history as “The Cowboy.”

For a town of 2,400, Ellsworth keeps its history alive with big dreams. The biggest? Turning the old Signature Insurance Building into the National Trail Drovers Hall of Fame, envisioned as an interactive museum, research facility, restaurant and theater.

Smaller dreams have already been realized to celebrate the history of Ellsworth’s cowtown glory days of 1871-1875. The Ellsworth Historical Plaza Walking Tour is lined with 17 frontier silhouettes and interpretive signs. The Hodgden House museum complex includes the stone livery, among the last liveries in Kansas still standing on a main street. And the 1873 limestone jail might not have a roof, but it hasn’t been torn down to make room for a McDonald’s.

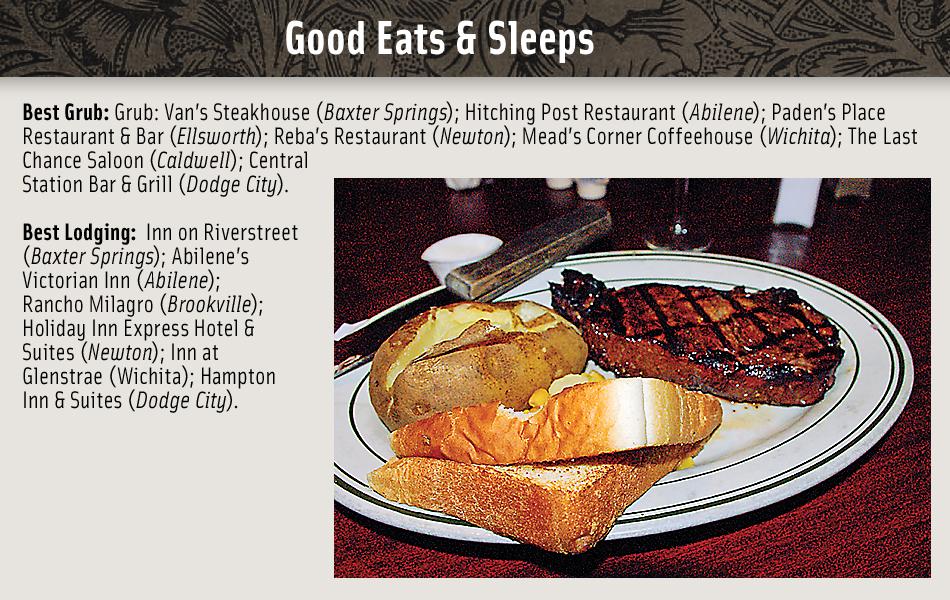

And you can still get a mighty good chicken-fried steak at Paden’s.

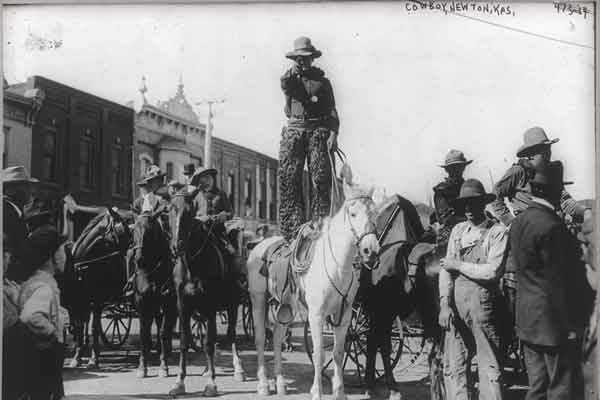

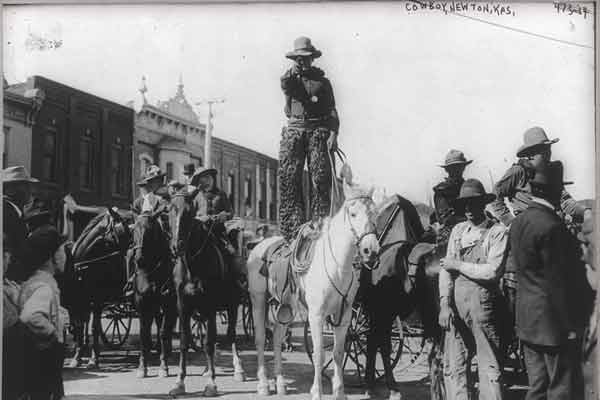

Newton: “Bloody and Lawless”

On the other hand, just north of Wichita, I find that the town once dubbed “Bloody Newton, the wickedest town in the West” has become the “Breadbasket of the World.”

The cowtown era “is not our primary focus,” Kris Schmuker tells me at the Harvey County Historical Museum. “Our history didn’t start or stop there.”

But Milburn Stone, Doc Adams from TV’s Gunsmoke, was born in Harvey County!

Oh, well, you have to understand that this area is home to one of the world’s largest populations of Mennonites, and that’s where tourists focus. Not just at the historical museum, but even at North Newton’s excellent Kauffman Museum, although at the latter I do follow a walking path to a Chisholm Trail marker and look at the old cattle swales.

On the other hand, the food’s upscale and really, really good. And the only “Bloody Newton” vibe I really find is from irate and irrational drivers. It’s still a train town, and people get a tad angry when they have to stop for long freights. Then they take it out on drivers of Ford Mustangs with New Mexico plates. Maybe Newton has decided to focus on Mennonites and tasty bread and let Wichita deal with cowboys.

Wichita: “Cowtown”

Which Wichita does well. After a delightful stay at the Inn at Glenstrae, I head over in the morning to the Delano District to visit Hatman Jack.

Once, this district was where “anything goes in Wichita,” but today it’s fairly quiet. And Jack Kellogg isn’t just making and selling hats at his store. He’s the Delano’s resident historian.

“Wichita, in its infinite wisdom, had the Delano separated from Wichita proper,” Kellogg says, “so that those terrible statistics would not blemish the city’s reputation.” Of course, the city also decided to fine brothels, bars and gambling houses, leading to the old saying: “The streets of Wichita were paved with the sins of Delano.”

Hatman Jack’s isn’t the only place to learn about history. Old Cowtown Museum, founded in 1953 as a collection of five buildings, has continued to grow into an outstanding living history museum. The Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum has a collection of some 70,000 artifacts and tells the city’s history on the museum’s four floors from Indians to cowboys to farmers to aviators.

Even the neighboring Fidelity Bank, which has offices in the old Wichita Carnegie Library, pays tribute to the cowboy heritage. Bryan Haynes was commissioned to paint The Four Horsemen of Wichita, Spring 1871, which hangs on a second-floor wall and depicts Wichita leaders meeting with Texas drovers and persuading them to bring their beef to Wichita.

Caldwell: “The Border Queen City”

Down south, I learn that the “Border Queen,” Caldwell—just above the Oklahoma border—isn’t about to forget its cowboy days.

When the Opera House, which opened in 1881, was condemned and about to be razed, the Caldwell Historical Society bought the building for back taxes owed and began a four-year restoration project. Reopened in 2006, the Opera House is home to cultural and entertainment events, and has a number of historic displays inside.

This is where I meet historians Karen Sturm and Rod Cook, who begin telling me a million stories about Caldwell. I mean, they really like Caldwell. And aren’t about to let the town change.

Historic markers can be found across the city, detailing people, shoot-outs and saloons. More history can be learned at the Border Queen Museum and at Heritage Park, and the Last Chance Saloon, which serves great steaks. South of town, the “Ghost Riders of the Chisholm Trail” silhouettes brag about the town’s wild days.

“A small town has an advantage over a big city when it comes to preserving history,” Sturm says. “We get high school, even grade school kids involved in history, re-enacting, because this is their history, their heritage, that they’ve grown up with.”

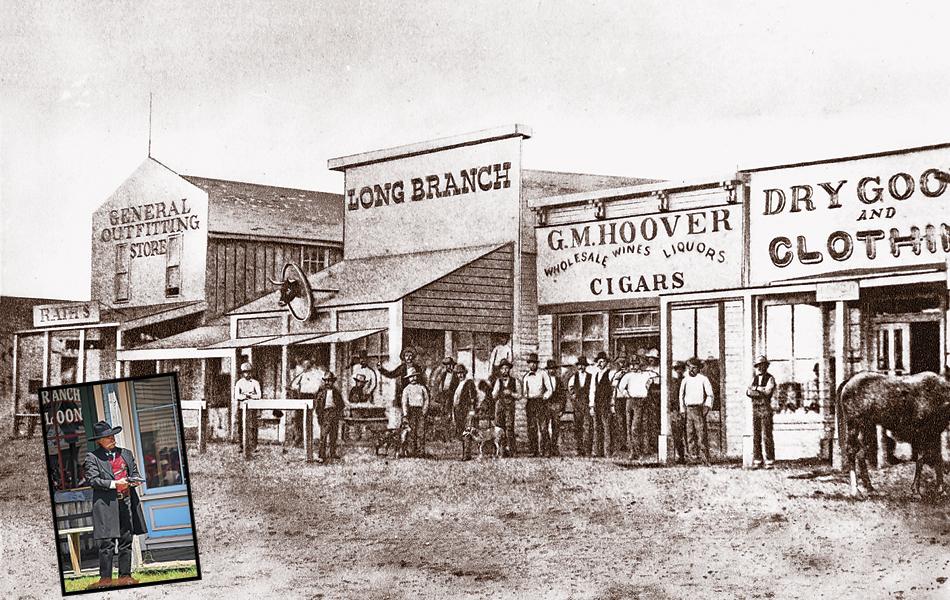

Dodge City: “Queen of the Cowtowns”

Of course, the Queen of the Cowtowns has never even considered forgetting its heritage. Welcome to Dodge City.

“People come here, and they don’t know what to expect,” Brent Harris tells me before we stroll through the Boot Hill Museum. “But they don’t expect this.”

Harris is Boot Hill’s marshal … ambassador … biggest fan.

It’s easy to think of the museum and its reconstructed Front Street and Boot Hill cemetery as a tourist trap, but the museum is filled with historic treasures of Dodge City’s past. Chalkley Beeson, who along with William Harris bought the Long Branch Saloon in 1878, was an avid collector. So when the Beeson Museum closed in 1964, Boot Hill acquired much of that estate.

Whether you’re looking for entertainment, a history fix or research, you’ll likely find it at Boot Hill.

And Dodge has even more. Tourists will find much to occupy their time at the Home of Stone and old Fort Dodge. And for those that want the gambling experience, Boot Hill Casino & Resort is ready to take your money. The games, of course, are honest these days.

“People come from all over the world,” Harris says. “Dodge City is a treasure, and I’m just proud to be a part of it. If you haven’t noticed, I’m pretty passionate about history and this town.”

Johnny D. Boggs worst part of his road trip was when he learned that Café on the Route in Baxter Springs, Kansas, had closed.

Photo Gallery

– Photo by Johnny D. Boggs –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

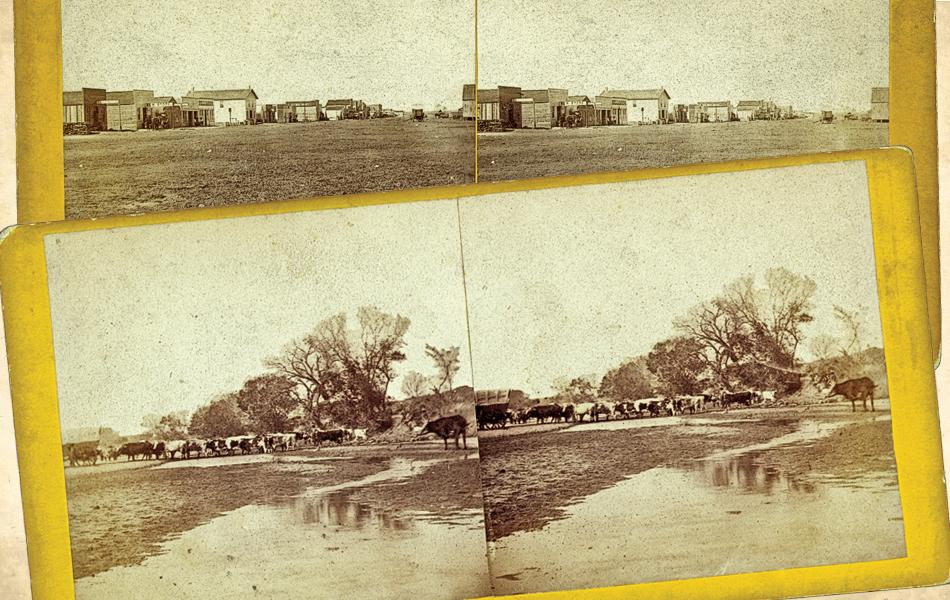

– courtesy Library of Congress –

– Harris photo Courtesy Dodge City CVB / historical photo True West Archives –

– Photo by Johnny D. Boggs –