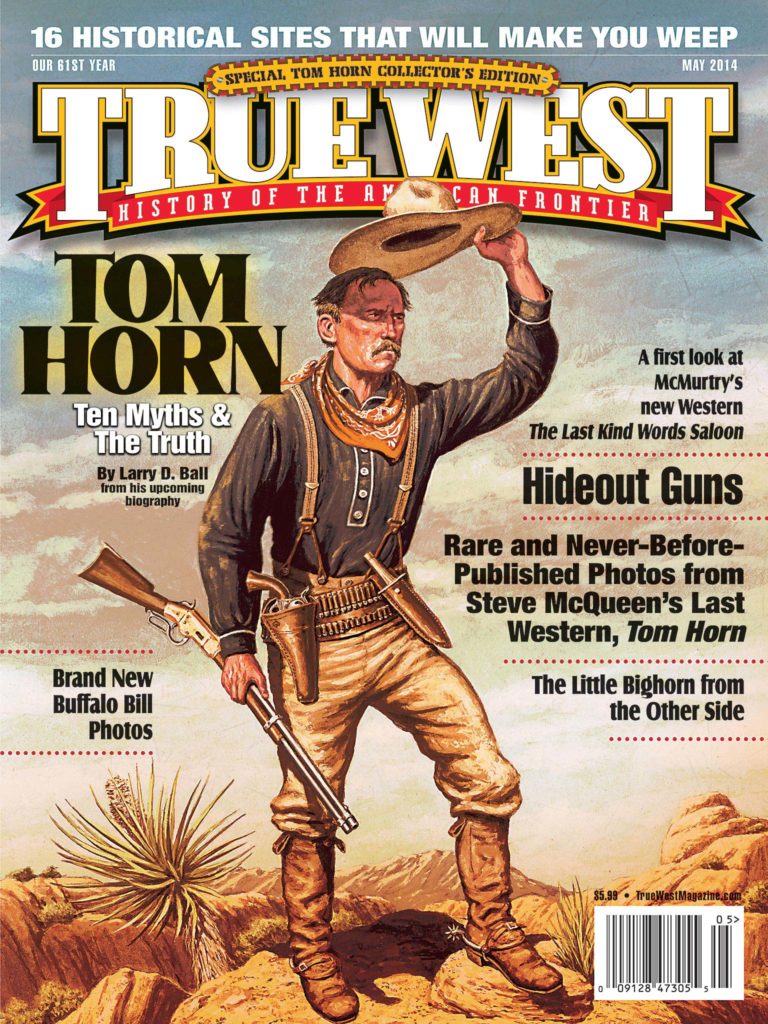

The Little Big Horn battlefield is the site of exquisite tragedy and triumph—depending on whose eyes are watching: tragedy for Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and half his 7th Cavalry, who were wiped out there in June 1876; triumph for the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, who won the battle to protect their ancestral lands.

The Little Big Horn battlefield is the site of exquisite tragedy and triumph—depending on whose eyes are watching: tragedy for Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and half his 7th Cavalry, who were wiped out there in June 1876; triumph for the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, who won the battle to protect their ancestral lands.

But for years, the National Park Service honored only the 263 cavalry soldiers who had died that day, most of whom were buried in a mass grave later on. For years, the site was called the Custer Battlefield in honor of the controversial soldier who had led five companies to their deaths.

Today, we know it as the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Last summer, the erection of a permanent Indian Memorial completed the story. Sioux leader Enos Poor Bear Sr. didn’t live long enough to realize that dream.

“My father worked on this since the 1950s,” Enos Poor Bear Jr. says. “He led the fight to change the name from the Custer Battlefield, and he wanted our ancestors recognized. He said that a memorial for the tribes must not only contain a message for the living, but also a tribute to the dead.”

Poor Bear Sr. pressed the issue hard during the 1960s, when he was chairman of the Oglala Sioux, and through the 1980s, as a member of the “Committee of Three” that also included Russell Means and Cheyenne leader Austin Two Moons. Means publicly began the fight by forcibly putting a plaque to honor the fallen warriors on the mass grave of the cavalry soldiers.

While some opposed any recognition to the American Indian side of the battle, many in the general public and political life saw the fairness of the fight.

“This began as a memorial to fallen soldiers, and Indians were seen as the enemy,” recounts Ken Woody of the National Park Service. “This became a hot spot for all issues on taking land; it became a soapbox for people to talk about injustice. There was anger by the general public on the unfairness. That’s gone now. Now we have monuments to both sides.”

Poor Bear Sr. died in 1991, before Congress authorized the Indian Memorial. Temporary panels went up in 2003, and permanent granite panels were installed by fall 2013. This June, on the 138th anniversary of the battle, the panels will be rededicated. Two spirit gates frame the 7th Cavalry memorial, while the 3,000-pound panels are engraved with the names of fallen warriors and memories from each of the 17 tribes they honor.

Poor Bear Jr. helped choose the quote to represent the Sioux. It is from Ta’Sunke Witko, better known as Crazy Horse: “My lands are where my dead are buried.”

The triumph of June 25-26, 1876, was short-lived for the Indians. Most had surrendered within one year, and the Army succeeded in seizing the gold-rich Black Hills of South Dakota.

Poor Bear Jr. hopes visitors to the site will see both sides to the story: “I want them to take away an understanding that this was a great accomplishment by our people in trying to protect our way of life. We had a place on Mother Earth, and in this battle, we protected her.”

Visit FriendsLittleBigHorn.com/meganreecethesis.htm to learn more about the history of the Indian Memorial. The author of three books, Jana Bommersbach has been Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and has won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards.