When Joe and Tony Gayton, the brothers responsible for creating Hell on Wheels, pitched their series to cable station AMC, a Western wasn’t necessarily the first thing they had in mind.

When Joe and Tony Gayton, the brothers responsible for creating Hell on Wheels, pitched their series to cable station AMC, a Western wasn’t necessarily the first thing they had in mind.

The Gaytons, separately and together, had a number of projects in their past, most of them action-oriented, though some were along the lines of Suspense and Mystery genres.

But AMC was having a lot of luck with Westerns, among them Broken Trail, and they’ve been blocking a lot of older Western films routinely on the channel. The idea of a Western seemed to suddenly take shape; as the project generated enthusiasm, as so often happens with Westerns, the notion of a long form Western series took on a life of its own.

“I remember the [PBS] documentary, the American Experience documentary, ‘Transcontinental Railroad,’” Joe says. “Seeing that, and thinking, dang! There’s a lot of great stuff in there: characters, ideas, history—seeing the scope of the story. And so we pitched it as a Western, based on the Transcontinental Railroad, and they bought!”

Hell on Wheels seems natural enough, in particular the idea of a movable town and the people who live there—the workers, the makers and shakers, and the entertainers—makes it an unrooted version of the HBO series Deadwood. The driving theme is the train; people who construct it, the entrepreneurs who profit by it and the environment that it drives through, which impacts the American Indians.

“It’s going to grow, Hell on Wheels, the town,” Joe says. “They were dragging an Eastern ghetto like the [neighborhood] Chelsea. At the same time, we wanted the series to have a classic John Ford look on the outside, but when you go inside, it’s claustrophobic and dirty. So far, we’ve done a pretty good job. And, of course, it’s about the train.”

The train, the Union Pacific, is the single steel metaphor that drives the 19th century—it represented the future, travel, the Industrial Revolution, commerce and fantastic unimaginable venality.

“Paradoxically,” Tony adds, “because we have this through-line, this driving force, for the good of the country. And yet we have a lot bad stuff—violence, black-and-white issues—as well as a lot of juicy gray matter to deal with. This was probably the greatest achievement that had ever been accomplished, but at the same time, they were in front of two of the biggest issues to deal with: slavery and the treatment of Native Americans. It’s got both. And as the railroad is built, it’s really changing everything for the worst, for the buffalo, the Indians and their way of life—the final nails in the coffin.”

“We also like the irony that in opening out the West, it’s really closing down the West, the Wild West that we knew,” Joe admits.

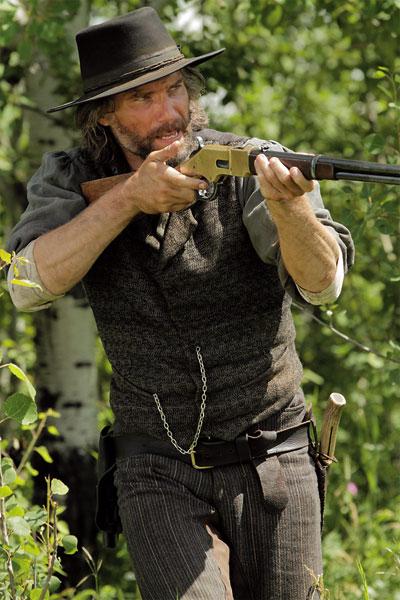

Added to the Gaytons is David Von Ancken, one of the executive producers of Hells on Wheels, who also directed the 2006 Western feature film Seraphim Falls. As to whether the revenge theme came from Seraphim Falls and Ancken or somewhere else, the central figure of Cullen Bohannon (Anson Mount) lives for a dream of violent retribution.

“What I like about it, what I like about this character, is you have the essential conflict of the revenge, which we’ve seen before this, and he’s led by his gut,” Anson Mount says. “And his gut tells him right and wrong, but it constantly leads him off the track, off his primary objective, involves him in all these situations that are keeping him from achieving this main objective.

“So while his motivations are nefarious. His heart is good. And that’s what keeps him from being able to achieve his objection—now I’m not going to tell you how far he goes, but that’s his primary conflict.”

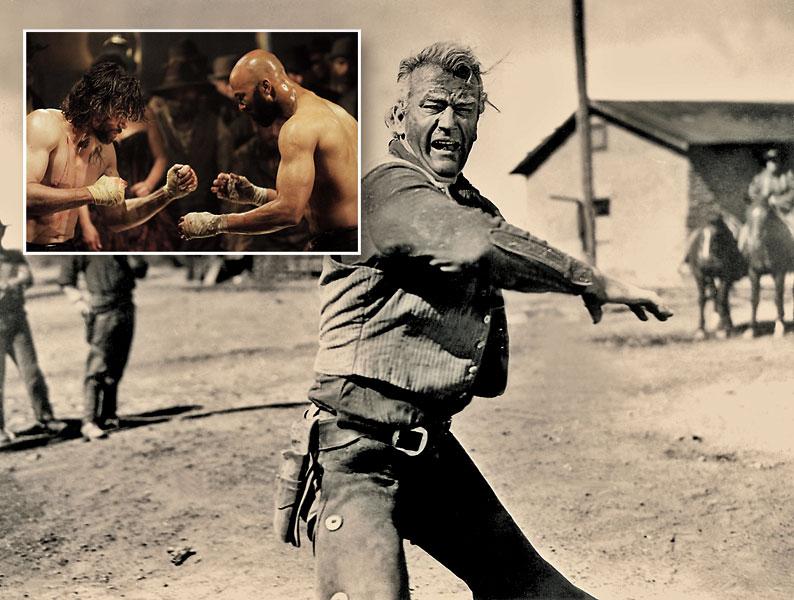

“We have a great many influences in this series—certainly John Ford and Once Upon a Time in the West, which is all about the train,” Tony says. “But the other day, I watched Red River and the part where the train comes to Kansas.

“We hadn’t seen the movie in years and then, we thought, there’s a lot of Cullen in the John Wayne character—he’s not the most likable guy in the world—but he can’t help doing the right thing. But he does a lot of wrong things on the way.”

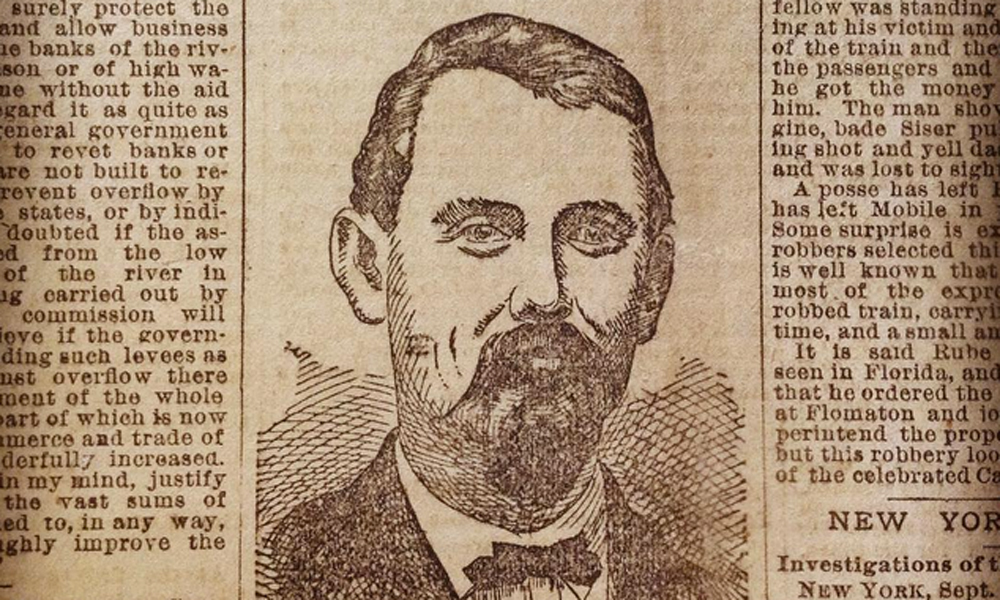

The other central character in the drama of Hell on Wheels is Thomas “Doc” Durant, played by Colm Meaney. Durant was a real 19th-century figure we see more commonly as a robber baron, even though he really was a phenomenally successful and unscrupulous hustler who stole a fantastic amount of money and, at the same time, built a train.

Durant sold phony stocks, worked for a while with Abraham Lincoln and, among other things, sold contraband cotton to the North, from the South, during America’s Civil War.

“Durant is a complex figure—he’s who he is, but he’s also something of a composite, historical,” Joe says. “We know that Durant was spending most of his time in Washington as the train was being built. But we need him on the site, in the series, on the construction of the trains, for drama purposes.

“We think of him as the world that keeps on giving, and we had to be careful to find a way to humanize the character. We didn’t want to make this a history lesson.”

“But we also need to see Hell on Wheels as a simple way to create comparisons and parallels to what’s going on in the modern age, with corruption and greed, with the hedge fund scandals and the real estate bubble,” his brother Tony adds. “But what we see, then, is that in spite of the graft and dealing, we wanted them to see the railroad as something that we could see and touch. We want people to say, back then, ‘We made this! We built this!’

“I don’t know what a hedge fund is—that’s just smoke and mirrors. But I know what a railroad is, and they knew what it was.”

As the producers and the cast and crew begin to prepare to return to Alberta, in Canada, for the second season, we’ve come to know more about the story and the characters. The most interesting thing about Hell on Wheels is how determined the creators seem to be to make sure that we are constantly surprised, and that they foil expectations at every turn.

This is a violent story, and very dark. No one is going to confuse it with Broken Trail or Lonesome Dove.

“I’m a big reader of Cormac McCarthy’s books, and [Joe and Tony], they’re McCarthy fans. There are similar characters in McCarthy’s, especially

in [his novel] Blood Meridian—which I think was a huge influence to me,” Mount admits.

“But the primary influence is just reality. Growing up in the South, I learned a lot about the Civil War. But we did not get as great [an] education on Reconstruction, so I did not realize that it was the engineering marvel of the 19th century, the Transcontinental Railroad. And it’s a fantastic framework for a Western because it was lawless—not only was it lawless, it was mobile, in every sense—there’s no foundation, nothing to hang on to, but that

it’s constantly moving. That’s what makes this story different—there’s movement, but no framework, either physically or morally.”

I, for one, can’t wait to see how the next season unfolds.

Great Train Westerns

Trains are as much a part of the Western as guns, cows, hats, Indians, horses and attitude, and trains had as much attitude as outlaws. In fact, trains, like banks, were a universal adversary—the stuffed-vest executives who owned them, the clerks who protected their safes (the unfortunate Mr. Woodcock in Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid), the engineers, the brakemen and firemen who were forever being held up by daring desperados, not to mention the porters and passengers.

But trains are sexier than stagecoaches and infinitely sexier than banks: you can chase them and leap from horseback onto them while in motion, and yelping Indians with bows and rifles can fire on them.

No question—the train is the king. Without trains there’s no Great Train Robbery (first Western film), no Jesse James, no Wild Bunch or Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid, no steam or whining brakes, no noisy machinery and, least of all, no lonesome whistles. For outlaws and Indians, trains were how we measured our bravado—before trains, we chased woolly mammoths and, later on, bison.

But trains reached all the way to the imaginations of ambitious men, to closed rooms where cigar smokers figured out ways to build tracks while they stacked, and sacked, loot, which is what the AMC series Hell on Wheels is largely about.

We needed men to physically build the trains, and design and finance them. For our purposes, we needed people to take advantage of real estate—moustache twirlers who stole land for the trains, and good guys, like Johnny Guitar and the spectacular Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West—one of the greatest train movies ever. Speaking of which, for a treat, see the Mongolian 15-minute train shoot-out in The Good, The Bad, The Weird—it’s incredible, and yes, it’s a Western.

Trains are big mojo in the world of Western cinema: The Iron Horse, Union Pacific, Denver and Rio Grande, Canadian Pacific, Carson City, Buckskin Frontier and so many others. I’d also add in The Wild Bunch, largely because the film’s characters are defined by the relationship between the outlaws and a train tycoon, but also because the train robbery, and its destruction, is one of the greatest sequences in movie history.

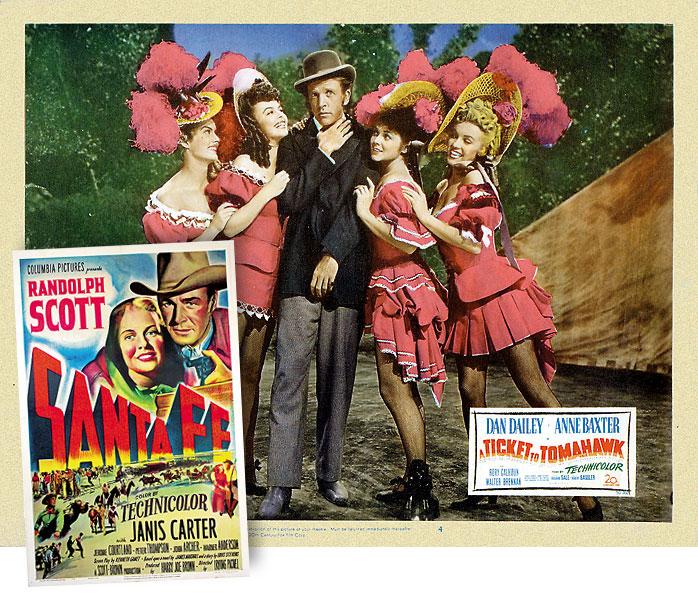

Two other train pictures deserve special attention: A Ticket to Tomahawk and Santa Fe. Randolph Scott shows up in a great many significant train pictures—Canadian Pacific and Carson City, among others, but in Santa Fe, we see a version of Reconstruction—Scott’s two brothers are determined to have vengeance for the Civil War, while Scott is starting a new life, working on the train.

What Santa Fe has in common with Hell on Wheels is that the mobile drinking and gambling tent that follows the train workers is what Scott is determined to destroy, even though his brothers are working there. It also has a scene where Scott allows an Indian chief to drive a locomotive engine—a somewhat different look at a similar event in Hells on Wheels. Santa Fe is not a great picture, but it’s a solid Scott effort, which is true of almost all of them, and, in the background, it has a lot of what draws us to Hell on Wheels.

The other picture, A Ticket to Tomahawk, is all about competing railroad lines, which is a fairly routine plot device, but it has spirited music (by Dan Dailey), dancing, some fun writing, some great scenery, a spunky rootin’ & shootin’ cowgirl (Anne Baxter), some interesting Arapahos and a little bit of Marilyn Monroe.

Now that Hell on Wheels has closed its first season and is preparing for the second one, think of Santa Fe and A Ticket to Tomahawk as refreshing palate cleansers.

Henry Cabot Beck is the Film Editor for True West, writes about pop culture in general for other publications and is a member of the Phoenix Film Critics Society.

Photo Gallery

Funding a transcontinental railroad was often an arduous task, and the competition between different lines was fierce; such conflict is at the heart of