You’ve gotta love Texians and the Confederate government. They actually thought this was a good idea.

You’ve gotta love Texians and the Confederate government. They actually thought this was a good idea.

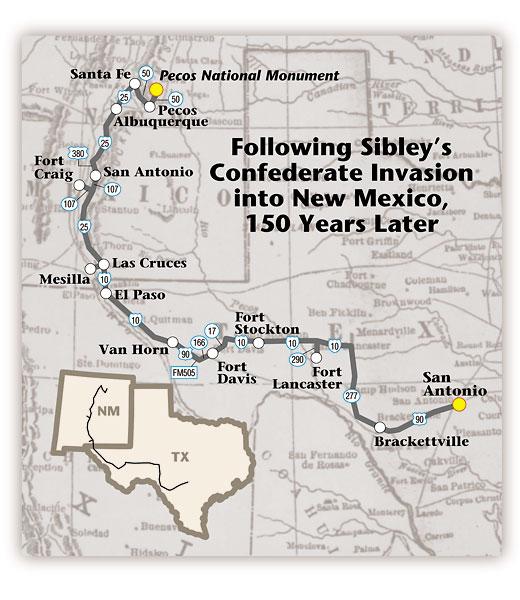

In 1861, Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley approached the Confederate brass with an ambitious—okay, ludicrous—plan. Sibley would lead an army of Texas volunteers from San Antonio out west. In New Mexico, they would capture Albuquerque, Santa Fe and Fort Union, and proceed on to Colorado to secure the gold and silver mines there. Ultimately, the Rebels would claim what’s now Arizona and California for the Southern cause.

Give Sibley some credit. He invented the Sibley tent and the Sibley tent stove. Yet he believed his army could live off the land on their march west and north. He also believed New Mexicans would flock to the Southern cause. (Yet, as the late historian Don E. Alberts noted, native New Mexicans “detested Texans” more than the Union soldiers.)

Sibley, it was said, had a drinking problem. The brass in Richmond, Virginia, couldn’t have been teetotalers to sign off on his plan.

A Trail of Texas Forts

Be that as it may, in the autumn of 1861, Sibley led his volunteers out of San Antonio, a historic city that offers today’s visitors the River Walk, the Witte Museum, the Buckhorn Saloon & Museum, SeaWorld, Schlitterbahn and the mango ice cream at the Menger Hotel. Fort Bliss, in El Paso, lay roughly 630 dry miles away.

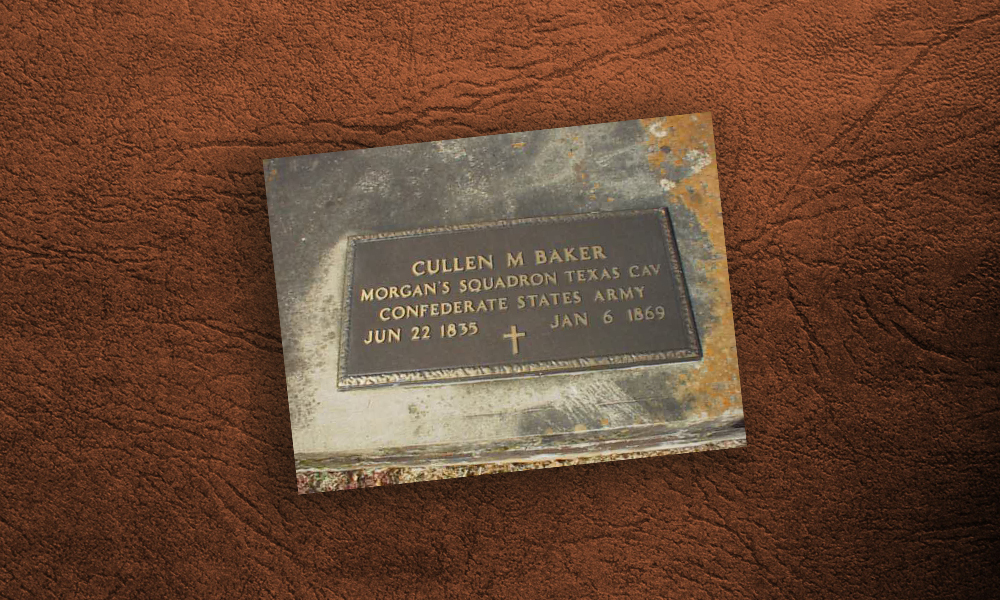

By then, Union troops had abandoned their forts in Texas, so Sibley and his roughly 3,700 men traveled down the stage road, often camping near or at the ex-Yankee military posts. This is still a good thing to do to break up that long drive across west Texas.

For instance, a good road trip stop is Brackettville. Fort Clark was established in 1852, and the federal Army would reoccupy it in 1866, where it would play major roles in the Indian wars. In fact, Fort Clark wouldn’t be abandoned again until 1946. Of course, it’s not abandoned these days. The grounds have been transformed into Fork Clark Springs. The guardhouse is now a museum, open Saturday and Sunday afternoons. The cavalry barracks have been renovated into a motel. And there’s an 18-hole golf course.

There’s even something to see in Sheffield, but not many people take time to visit Fort Lancaster State Historic Site. At least, that’s the sense I get, because the ranger working there when I drop by just won’t stop talking. That’s a good thing.

Lancaster was established in 1855, but was abandoned on March 19, 1861. Companies of the Texas Mounted Rifles manned the fort for a while, before the feds came marching back in 1867. There’s not much left of the post, but the visitors center has a nice little museum, and that ranger will answer any question you have. In fact, chances are you won’t even have to ask. He’ll just tell you.

Down I-10 lies yet another historic stop: Fort Stockton, established in 1859, evacuated in 1861, home to Confederates for a spell and then burned. The water here still tastes like it could burn. The Army re-established the garrison in 1867, but it wasn’t the most popular posting. As visitor Emily K. Andrews noted in 1874: “The lack of shade and the want of grass on the Parade make a glare as you look upon it almost intolerable….” More tolerable today is the reconstructed Barracks No. 1, which houses a museum. You can also tour the original 1868 guardhouse and one of the remaining three officers’ quarters that has been restored to its 1870s appearance.

Even today Lancaster and Stockton are mighty bleak, but finally, Sibley’s men found an oasis in west Texas. When Col. James Reily reached the beautiful Davis Mountains, he and his men scored some hooch and “got tight.” In fact, Reily and some officers stayed in Fort Davis for a spell, “tanked up considerably.” Apparently, Sibley wasn’t the only Texas officer with a drinking problem.

There’s more to do in Fort Davis than drink, which is a good thing, since much of Jeff Davis County is dry. If you’re thirsty, you can buy booze at the Hotel Limpia’s Sutler’s Club, and this historic hotel is perhaps the nicest place to stay in a great little town. Once you’ve slaked your thirst and filled your belly, check out Fort Davis National Historic Site, one of the best and best-looking posts in the Southwest. And hit the Overland Trail Museum, since we’ve basically been following the San Antonio-El Paso Road.

From Fort Davis, head up to Van Horn —with a stop at the McDonald Observatory for you sky-watchers—where you should fortify yourself on chiles relleños at Chuy’s (a favorite of NFL broadcaster John Madden), and journey on to El Paso.

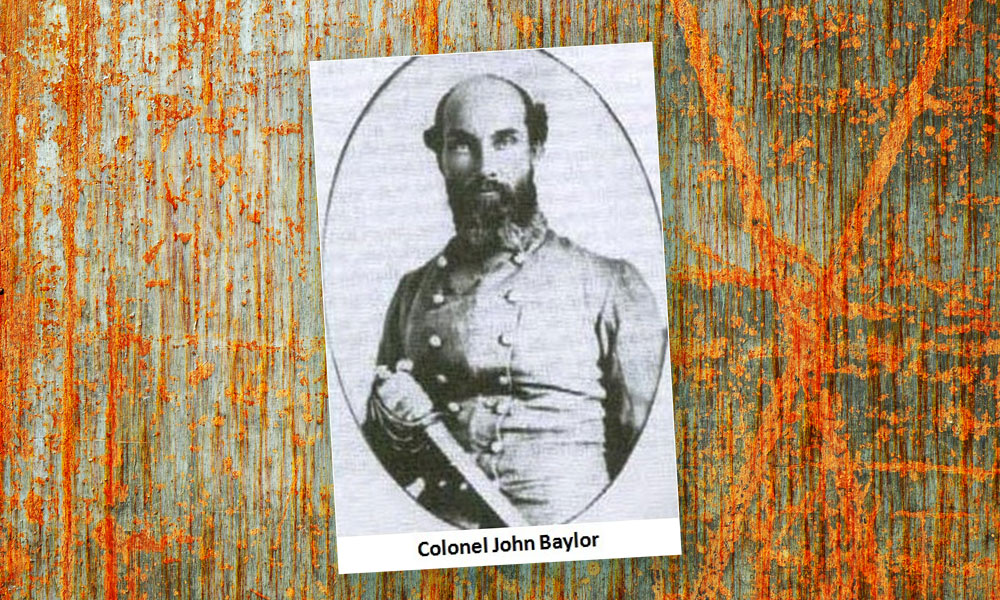

On December 14, while at El Paso’s Fort Bliss, Sibley assumed command of “all the forces of the Confederate States on the Rio Grande at and above Fort Quitman and all in the territory of New Mexico and Arizona.”

Alas, Tony Lama, Lucchese, Champion Attitude, Stallion, J.B. Hill and Rocketbuster weren’t making awesome boots in El Paso in 1861, but you can sure shop for boots here today. And don’t forget to check out the El Paso Museum of History and Old Fort Bliss, a reproduction of the original 1849 fort. Bliss is still an active post, so you’ll need a valid driver’s license, vehicle registration and proof of insurance to get in. No verification is needed, however, to sample the carnita plate at Avila’s Mexican Food.

Invading New Mexico

Finally, the Rebels reached New Mexico. It was southern New Mexico. In fact, meetings in New Mexico’s Mesilla and Arizona’s Tucson had led to the southern section to secede from the Union and become the Confederate Territory of Arizona. But others weren’t happy to see the Rebels. Indians raided the horse herd. A dust storm peppered the invaders.

Oh, things were fine in Las Cruces and Mesilla. In fact, things are still fine there. Mesilla, once the gateway to southern New Mexico (Billy the Kid would be tried for murder here in 1881), is a charming town of shops, art galleries and restaurants with an old adobe feel. Vibrant Las Cruces offers a score of museums, ranging from the New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum and the Museum of Natural History and Science to the Las Cruces Railroad Museum and the Branigan Cultural Center.

With such a charming welcome, Sibley sent Capt. Sherrod Hunter and 200 men to Tucson (the battle at Picacho Pass, between Tucson and Phoenix, would end that little escapade), while Sibley took the rest of his force north.

The troops got their first real taste of battle on February 20-21, 1862, at Valverde, a few desolate miles south of San Antonio, New Mexico, near Fort Craig.

Colonel Edward Canby commanded the federal garrison, which included federal troops and Colorado and New Mexico volunteers and militia. One regiment of New Mexico volunteers was commanded by legendary frontiersman Kit Carson, so you knew the Rebs were in trouble.

By Eastern standards (Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Franklin), Valverde wasn’t much of a battle. Losses totaled fewer than 500 Union casualties and nearly 230 Confederate, though I imagine participants thought the fight was hot and savage enough.

Although the battlefield of Valverde, which is three miles north of the fort, is on private land, Fort Craig lies in ruins on Bureau of Land Management property. Chances are you’ll be able to tour the grounds alone.

Canby withdrew back to Fort Craig, leaving the Rebels claiming victory. Sibley didn’t have enough men, supplies or patience for a siege, and he wasn’t stupid enough to charge the fort’s thick walls. So he moved north, leaving Canby in his rear. He thought he could get resupplied in Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

“He also thought they could live off the land, and this was in the winter,” the woman at Fort Craig’s visitors center and museum tells me with a laugh. “Look out there. This is a desert.”

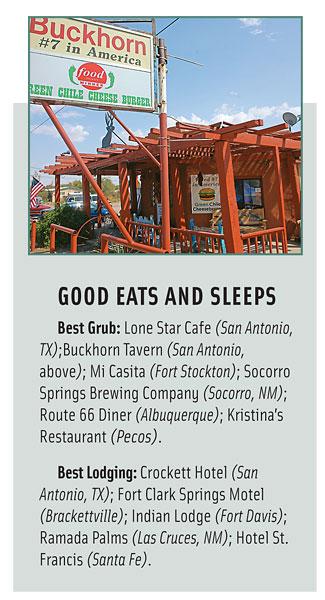

They call this area Jornado del Muerto (Journey of the Dead). It’s still hard to find life here, although the winter months at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge offer a birder’s paradise. And the green chile cheeseburgers at San Antonio’s Buckhorn Tavern or the Owl Bar are a carnivore’s delight.

Sibley’s invaders must have been exhausted by the time Albuquerque fell on March 2. On the Old Town Plaza, you can see two replica Mountain Howitzers that the Rebels buried nearby in April when they were retreating back to Texas. The original cannon barrels are displayed at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, walking distance from the plaza.

On March 13, the Confederate flag flew over Santa Fe.

“The houses in Santa Fe,” Texas soldier A.B. Peticolas wrote in his journal, “though altogether built of adobes, are of a better sort than any I have yet seen.”

Tell me about it. My wife’s a realtor in this town. Visitors are often blown away by how much a house here costs.

But it’s a great city to visit. The New Mexico History Museum is first-rate, as is Battlefield New Mexico, a two-day event of Civil War lectures and re-enactments each May at the fabulous living-history museum, El Rancho de las Golondrinas.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass

Sibley and his men knew they’d have to whip up the Yankees at Fort Union if they wanted that gold, so they headed on toward Colorado. They only got as far as Glorieta Pass near Pecos. There they met their Waterloo on March 26-28.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass has been called the “Gettysburg of the West.” Yeah, right. Roughly 100 men died on both sides combined during the Glorieta fight versus the approximately 8,000 deaths at Gettysburg. But Glorieta did turn the tide, and it turned back Sibley.

Actually, the Confederates had won the battle, tactically speaking, when they succeeded in pushing the Union force back through the pass. But then Colorado volunteers under Methodist parson John Chivington found the Rebs’ supply train in Apache Canyon and destroyed it.

Instead of claiming glory, the Rebels retreated back to Santa Fe, back to Albuquerque, all the way back to Texas. Chivington was the new Western hero. Two years later, he became the West’s worst villain after leading the massacre at Sand Creek.

The Glorieta battlefield is spread out, but Pecos National Historical Park in Pecos conducts two-hour van tours on Saturday afternoons. You can also take a 2.3-mile “Battlefield Trail” by signing in at the visitors center and picking up a trail map and gate code.

Texians, by the way, are not only allowed on both the tour and the trail, they are even welcome.

Johnny D. Boggs recommends Don E. Alberts’s The Battle of Glorieta: Union Victory in the West and Albuquerque writer P.G. Nagle’s novel Glorieta Pass.

Photo Gallery

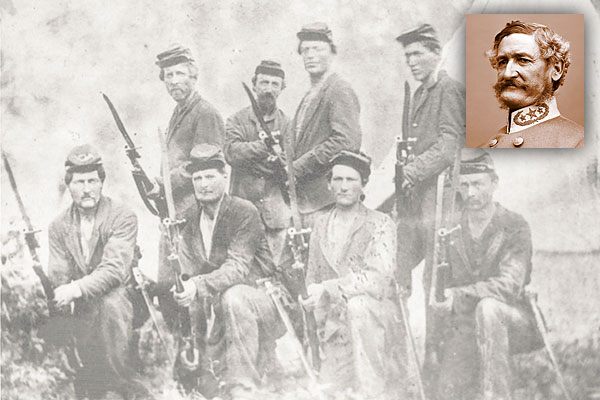

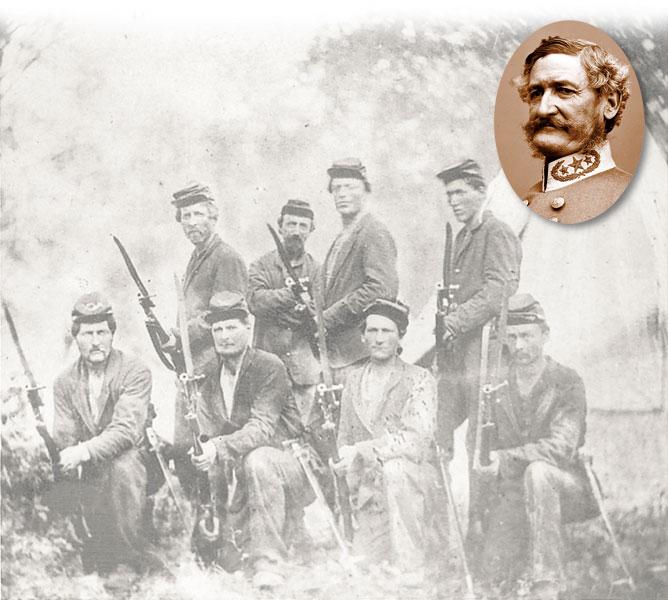

In 1856, military officer Henry Hopkins Sibley (inset) patented his Sibley tent, a 12-foot-high conical tent supported by a central pole. Ironically, when Sibley resigned from the U.S. Army to fight for the Confederates, the Union Army used nearly 44,000 Sibley tents. Shown here are some 8th Kansas Union soldiers, in 1862, by a Sibley tent.