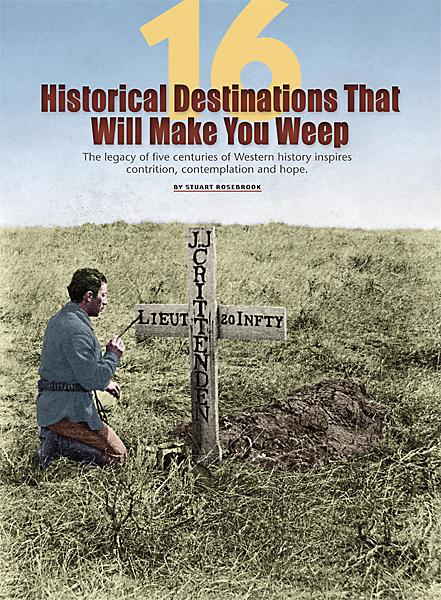

The American West, imagined and celebrated worldwide in art and literature, film and television, is equally a land of grace and grief. Since Columbus sailed the Atlantic, world history changed, not just in the Americas, but, around the globe, with the near immediate exchange of peoples, culture, food, precious metals, commodities, politics, religion, animals and disease.

The American West, imagined and celebrated worldwide in art and literature, film and television, is equally a land of grace and grief. Since Columbus sailed the Atlantic, world history changed, not just in the Americas, but, around the globe, with the near immediate exchange of peoples, culture, food, precious metals, commodities, politics, religion, animals and disease.

The story of the European-American settlement of the Western United States, and the legacy of the last five centuries of history, good and bad, will equally elate and temper one’s imagination as you understand the heartache and loss which happened with such violence and conflict as generations struggled, fought and died to control the land and rich resources of the American West.

For the first time in True West magazine, we share with you our top historic Western sites guaranteed to make you cry, get misty or at least genuflect on our history—and the strength of the generations who have endured and persevered—no matter the gravity of the tragic events of the past.

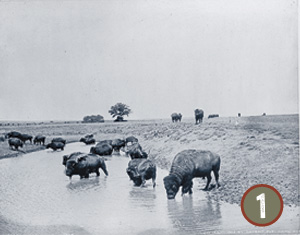

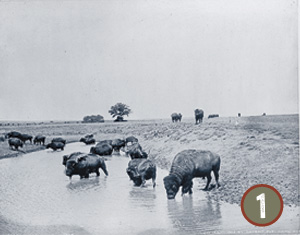

1:: Great Plains of North Dakota: The Near-Extinction of the American Bison

1:: Great Plains of North Dakota: The Near-Extinction of the American Bison

Once roaming the continent from Canada to Mexico, estimated at one time to number more than 50 million, the near extinction of the bison in the 1870s, and the collapse of the indigenous American Indian cultures dependent on the nomadic herds, is unfathomable to modern Americans. Many factors, including drought, the introduction of horses, cattle and sheep, and overgrazing and American Indian tribes overhunting prior to the Civil War, was the perfect mixture to create the calamity of the buffalo. The purposeful destruction of the last six million buffalo to destroy the culture of the Plains Indian tribes remains one of the great tragedies of the settlement of the post-Civil War West. In 1886, a young Iowa naturalist, William Temple Hornaday went to Montana to study one of the last wild herds of bison. His call to action in his ground breaking study, The Extermination of the American Bison, saved the noble animal, which had dwindled to just more than a thousand, including the Yellowstone herd of 200 (left) protected in the national park. Today, the buffalo in Yellowstone are one of the most visible and important symbols of the American conservation movement, with more than 220,000 on private and public lands. When you walk the grounds and visit the National Buffalo Museum in Jamestown, North Dakota, in the heart of the Northern Plains, your guaranteed to shed a tear for the keystone species the Lakota, the Buffalo Nation, called tatanka.

Experience History Today @ National Buffalo Museum, Jamestown, North Dakota, BuffaloMuseum.com; Yellowstone National Park, NPS.gov; Draper Natural History Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, CenterOfTheWest.org

2:: Acoma Pueblo: Acoma Pueblo Battle and Massacre, Acoma, New Mexico

2:: Acoma Pueblo: Acoma Pueblo Battle and Massacre, Acoma, New Mexico

The Spanish Empire’s lust for land and wealth, in competition with its European and Ottoman rivals, had hardened its soul, even when carrying a missionary cross in the one hand opposite the sword. Across the Americas, Spanish violence and exploitation of the indigenous peoples, including slavery, mass murder and Western diseases led to the death of millions, is overwhelming to contemplate. In New Mexico, in 1599, a young conquistador, Don Juan Onate, given the grant to settle the region, took offense to the killing of a dozen of his men in a skirmish at Acoma Pueblo (below). In retaliation, he ordered his soldiers to attack the Pueblo. More than 500 warriors were killed and 300 women. Of the approximate 5,200 Acoma Indians still alive, Onate ordered every male over 25 to lose their left foot (only 24 did) but all males, 12 to 25 and all females over 12, were dispersed into slavery for 20 years. A long history of mistrust between the Spanish and American Pueblo Indians, which ultimately resulted in the Pueblo Revolt, was once again evident in 1998, on the 400th anniversary of Onate’s founding of New Mexico. In Acalde, New Mexico, the right foot was cut off the conquistador’s statue, symbolically demonstrating that the Acoma people still grieve for those treated so viciously four centuries ago.

Experience History Today @ Pueblo of Acoma, New Mexico, PuebloOfAcoma.org; Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Albuquerque, IndianPueblo.org and New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, NMHistoryMuseum.org

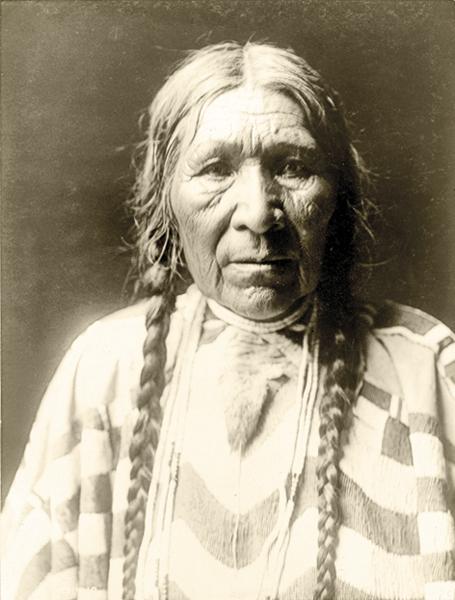

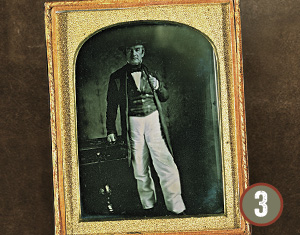

3:: Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma: The Trail of Tears

3:: Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma: The Trail of Tears

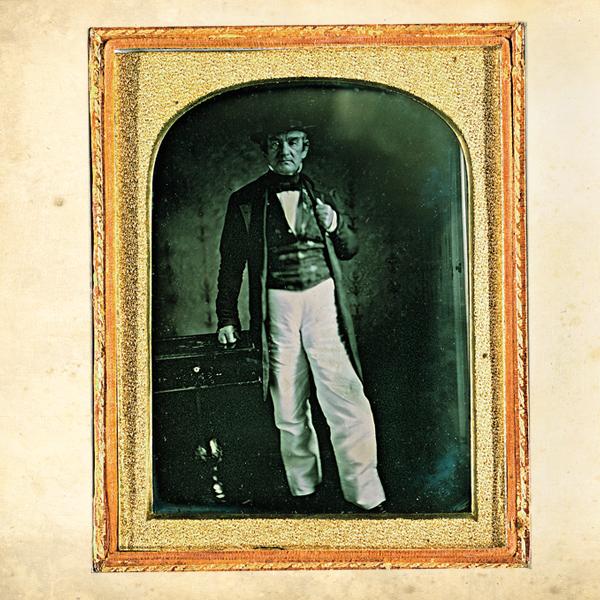

When President Andrew Jackson enforced the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the majority of Indians east of the Mississippi were moved into the Indian Territory of the future state of Oklahoma. The Indian Territory, became the most populated Indian state in the nation, forever defining the cultural future of the Eastern Tribes. The Eastern Indians, many decimated by war, disease and competition for natural resources, were forcibly removed from all states in the East, including the Five Civilized Tribes of the South, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole, including Cherokee leader John Ross (above) whose wife died on the way to Oklahoma. The Choctaw went first in 1831, the first “trail of tears” to Oklahoma, where they would be joined eventually by more than 40,000 American Indians forcibly relocated from their homes, thousands dying along the way. National historic trail markers have been placed in nine states from Georgia to Oklahoma, as well as numerous historic sites and museums, as symbolic reminders of the tragedy of the Trail of Tears.

Experience History Today @ Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma, CherokeeHeritage.org, Five Civilized Tribes Museum, FiveTribes.org, Muskogee, Fort Gibson Historic Site, Fort Gibson, FortGibson.org; Chickasaw Cultural Center, ChickasawCulturalCenter.com; and, National Park Service National Guide to Trail of Tears Historic Sites, NPS.gov

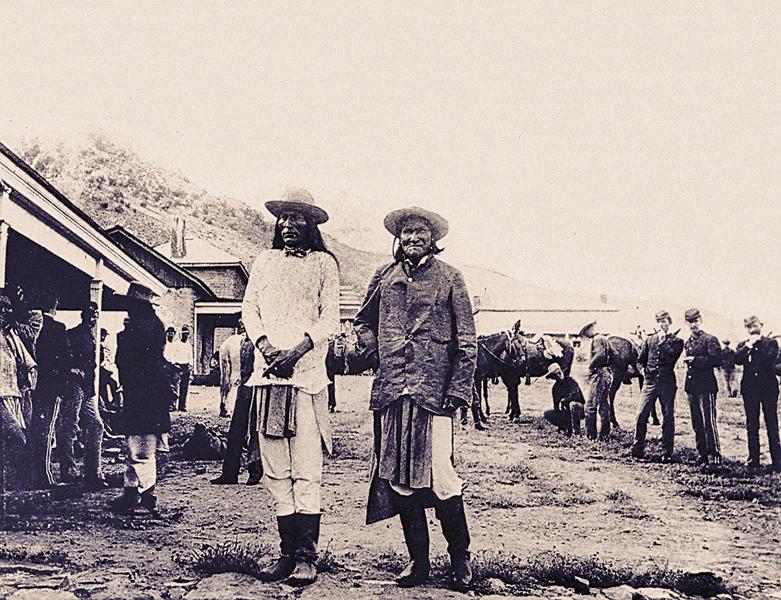

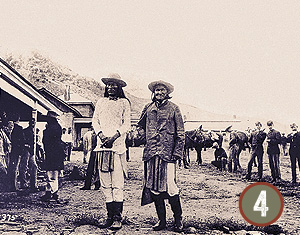

4:: Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Bowie, Arizona: The War with the Chiricahua

4:: Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Bowie, Arizona: The War with the Chiricahua

The battle for control of life giving waters of Apache Spring near Apache Pass in the northern foothills of the Chiricahua Mountains is symbolic of life in the desert Southwest of the United States and northern Mexico. When the Americans took over the region from Mexico in the 1840s and 1850s, the United States had continental plans, including national roads and railroads across Apacheria, a broad space of the Southwest from West Texas to Arizona. The young Republic inherited centuries of conflict and distrust between the Apache with their neighbors, the tribes they raided regularly in the region, and the Mexicans, descendants of the Spanish who had been so so cruel, so long ago. When the Butterfield Stage Line was built across southern Arizona, the stage company built a station near the springs, a traditional camp for Cochise’s band of Chiricahua. Control over this simple spring, led to the Bascom Affair, and Cochise’s war with the United States. Fort Bowie was built nearby in 1862, but peace between the Chiricahua, led later by Geronimo (above, at right, with Naiche, son of Cochise, at Fort Bowie), would not end until 1886, and the tribe once feared by all, was shipped east to prison in box cars, including the Chiricahua Army scouts, never to return to Arizona.

Experience History Today @ Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Bowie, Arizona, NPS.gov; Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, ArizonaHistoricalSociety.org; and, Fort Huachuca Museum, Huachuca.com

5:: The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas: The War of Texas Independence

5:: The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas: The War of Texas Independence

Today, the Alamo (below) is remembered as the shrine of liberty and symbolic of the sacrifice Americans were willing to make to secure future lands for the expanding, young Republic. The War of Texas Independence in 1836 was a conflict of no quarter and little mercy, with the Alamo defenders killed to the last man and their bodies burned. In the next battle, at Goliad, after the Texas forcers surrendered to the superior Mexican force, Gen. Santa Ana ordered the rebels executed. More than 300 were marched out of town and shot; those who lived, were clubbed to death. Those who could not walk because of wounds, were killed where they sat. “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” became the battle cry’s of therevolution. At the the battle of San Jacinto, where Gen. Sam Houston defeated Mexican leader Santa Ana, the Texans returned the pain, inflicting unmerciful casualties on the once proud army of Mexico, killing 700 in a frenzied attack on the outmanned Mexicans. The battle for independence was won that day by Texas, and the legend of the Alamo, Goliad and San Jacinto live on, but without unimaginable and unmerciful casualities on both sides.

Experience History Today @ The Alamo, San Antonio, TheAlamo.org; Goliad State Park and Historic Site, TPWD.State.tx.us; and, San Jacinto Museum of History, LaPorte, SanJacinto-Museum.org

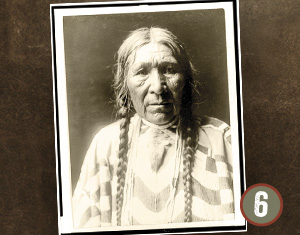

6:: Whitman Massacre, Walla Walla, Washington

6:: Whitman Massacre, Walla Walla, Washington

The Oregon Territory was first settled by missionaries following the end of the fur trade and before the Oregon Trail pioneers began crossing the country for new lands to farm. The Whitman’s, who built their Mission near Walla Walla, Washington, were killed in a massacre that still clouds regional history of the Northwest and led to retributions and mistrust of the Oregon Indian tribes which culminated eventually in the Nez Perce War nearly 40 years later.

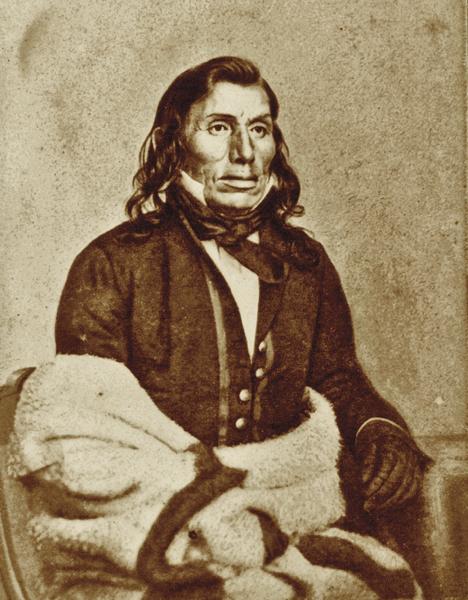

Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa, who with 11 others were murdered by Umatilla and Cayuse Indians on November 29, 1847, were accused by the Indians of poisoning 200 Cayuse that Whitman was inoculating for measles. The great cultural gap between the missionaries and Indian tribes had been building for 11 years, since the Whitman’s arrival in 1836 (they were some of the earliest families to settle in Oregon). The tragedy did not end that day. The Indians took more than 50 women and children hostage, exchanging them later for guns and supplies. One of the girls that died in captivity was the daughter of Joe Meek. Three years later, five of the Indian leaders were hanged for their crimes. Descendants of the Cayuse leaders, including the daughter of Tomahas (previous page), were moved on to a reservation near Pendleton, Oregon, with Umatilla and Walla Walla Indians. The incident remains one of the darkest in the West’s earliest days of settling the Northwest.

Experience History Today @ Whitman Mission National Historic Site, near Walla Walla, NPS.gov; Fort Walla Walla Museum, FortWallaWallaMuseum.org; and, Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture, Spokane, NorthwestMuseum.org

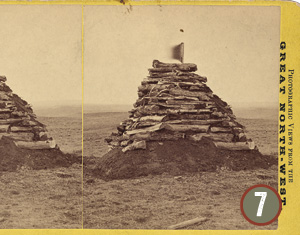

7:: Battle of Little Big Horn, Montana

7:: Battle of Little Big Horn, Montana

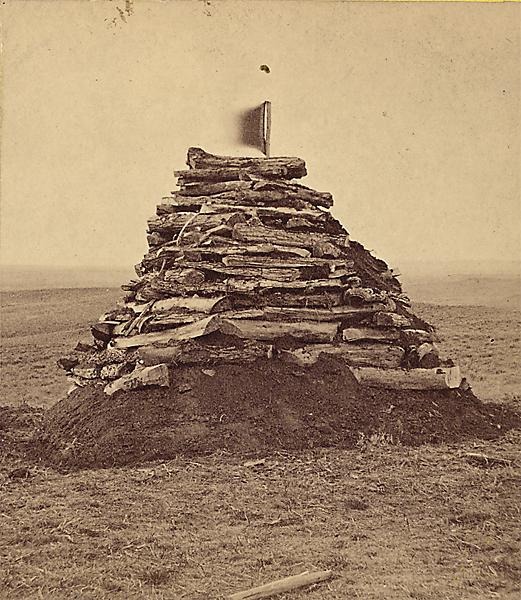

The defeat of Gen. George Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn remains one of themost poignant moments in American history. The story of the proud, overconfident cavalry leader who zealously underestimates the capability of his opponents, the 7th Cavalry under his command wiped out, and a legendary story of the West emblazoned by the fates on tablets of history. Yet, when you walk the grounds and hillsides of the battlefield,

when you walk through the cemetery, and pause at the monuments to the soldiers and warriors who fought and died that June day in 1876, you weep not just for the dead that day, but those who fought, died and suffered before and after Little Big Horn in the American-Indian wars. Little Big Horn’s national cemetery and the battlefield memorial (previous page) built over the mass grave of soldiers, is a sacred place. Keep your handkerchief nearby as you walk the hillside between the monument to the 7th Cavalry and the Indian Tribes, friends and foe, who fought and died so long ago.

Experience History Today @ Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument, Montana, NPS.gov; Custer Battlefield Museum, Garyowen, Montana, CusterMuseum.org; and, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, CenterOfTheWest.org

8:: Battle of Washita, Oklahoma

8:: Battle of Washita, Oklahoma

Symbolic of the post-Civil War battles under the national supervision of Sherman and Sheridan, between the Army and in the West, Custer’s “victory” over peaceful Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle is one of a series of U.S. Army attacks on Plains Indians who were preparing for peace. The winter conditions (previous page) exacerbated the conditions for the survivors and the East Coast papers began to question the Army’s policy of attacking peaceful tribes and the killing of women and children. Custer, who saw it as a military victory, not a massacre, never did completely recover from Washita in his military and political career, even labeled “Squaw Killer” by his detractors in the press, a moniker that surely haunted him to his final day on a hill above Little Big Horn.

Experience History Today @ Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, Cheyenne, Oklahoma, NPS.gov; Fort Sill National Historic Landmark Museum, Fort Sill, FortSillMuseum.com; Plains Indians and Pioneers Museum, Woodward, PIPM1.info; and, Southern Plains Indian Museum, Andarko, IACB.DOI.gov

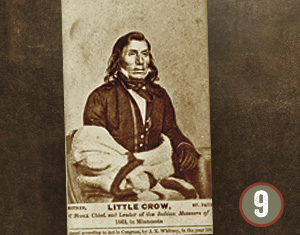

9:: Dakota Uprising, New Ulm, Minnesota

9:: Dakota Uprising, New Ulm, Minnesota

During the Civil War, the frontier settlers were vulnerable to attack by superior Indian forces, and in 1862 the Sioux uprising in Minnesota led to more than 600 settlers killed, dozens of Indian leaders hanged and the beginnings of a war with the Sioux that would infamously culminate nearly 30 years later at Wounded Knee. Chief Little Crow (above) was a respected leader of the Sioux, negotiating a peace treaty in 1851, but in 1862, after years of abuses towards his tribe, he had to support the war which would ultimately lead to the end of the Dakota Sioux culture in Minnesota and the hanging of 38 of his fellow tribal members (the largest hanging in U.S. history). The once revered peacekeeper found refuge in Canada, but on July 3, 1863, he and his son returned to his land in Minnesota to steal horses. He was mortally wounded and when his son was caught, identifying his father, Little Crow’s body was dug up, scalped, mutilated publicly and beheaded before being thrown into a garbage pit at a slaughterhouse. His remains have since been returned to his descendants and a statue in his honor stands above the Crow River in Hutchinson, Minnesota.

Experience History Today @ Pipestone National Monument, Pipestone, Minnesota, NPS.gov; Minnesota History Center, St. Paul, MinnesotaHistoryCenter.org; and, Brown County Historical Society Museum, New Ulm, BrownCountyHistoryMuseumMN.org

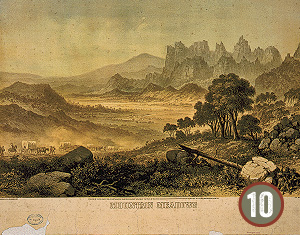

10:: Mountain Meadows Massacre, Mountain Meadows, Utah

10:: Mountain Meadows Massacre, Mountain Meadows, Utah

While history focuses on numerous atrocities against American Indians during the settlement of North America, the massacre on September 11, 1857, of 120 innocent emigrants. The Arkansas Baker-Fancher emigrant wagon train (above) was en route to California and were attacked by the Utah Territorial Militia, many dressed as Indians to lay blame against the local Paiute. The Nauvoo Legion, led by Isacc C. Haight. William H. Dame and John D. Lee (the only attacker to be tried, convicted and executed for his crimes, 17 years later), a five day battle occurred when the Legion attacked the settlers. Fearful of reprisals, Dame ordered a trick cease fire under a white flag, and when the Utah militia entered the wagon camp, they turned on the emigrants, marching them out and killing them all but the youngest. The bodies were left in shallow graves, many desecrated by animals, the belongings ransacked and stolen, and kind nearby settlers, rescued the living youngsters. Today, the Meadows is a national historic monument, a somber reminder of one of the most shameful events to occur along the pioneer trails to the West.

Experience History Today @ Mountain Meadows National Historic Monument, Mountain Meadows, Mtn-Meadows-Assoc.com; Natural History Museum of Utah, Salt Lake City, NHMU.Utah.edu; Pipe Spring National Monument, Pipe Spring, Kaibab-Paiute Reservation, Arizona, NPS.gov

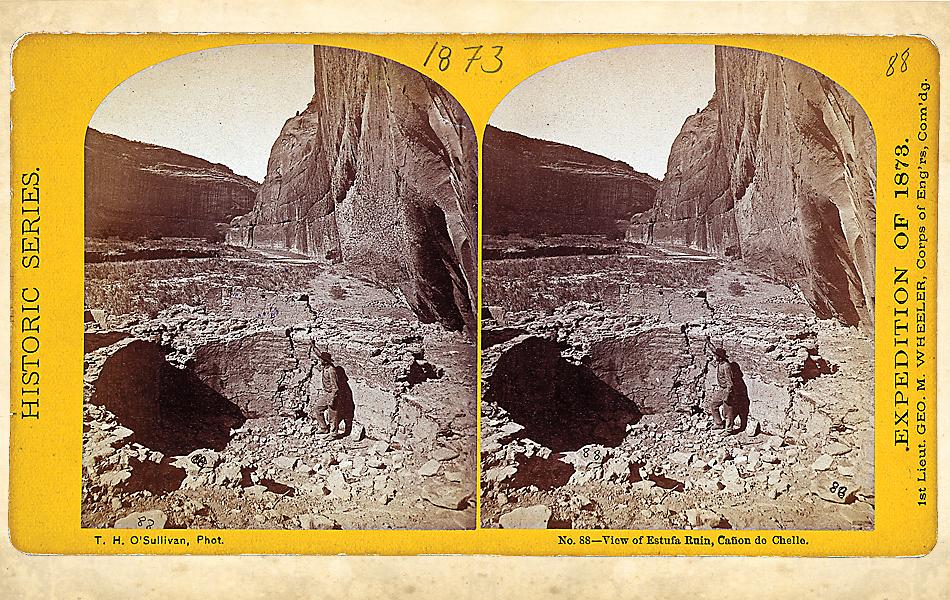

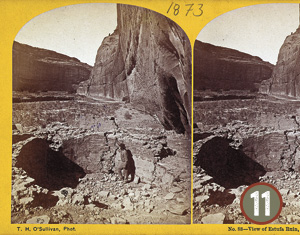

11:: Canyon de Chelly, Arizona

11:: Canyon de Chelly, Arizona

During the Civil War, the New Mexico Territory, like much of the Western United States, was undermanned in ongoing conflicts with local Indian tribes, including the Navajo, who for more than three centuries had been in conflict with the European-American settlers in the region. Kit Carson, who had settled in Taos, was tapped by the federal government to negotiate peace with the Navajo who would not end their heritage of raiding the stock of New Mexico’s ranchers and settlers. Carson marched his American force into Navajo Country and defeated the Navajo, including the bands who lived in Canyon de Chelly (left), where they farmed and tended their peach orchards, which Carson’s men chopped down. The Navajos, led by Manuelito, were marched to a lonely place called Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. The tribe was exiled for five years before they signed a treaty in 1868, promising never to make war with the United States again. In exchange for peace, they returned to their homeland, which today is the largest reservation in the country.

Experience History Today @ Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Chinle, Arizona, NPS.gov; Navajo Nation Museum, Gallup, New Mexico, GGSC.WNMU.edu; Bosque Redondo Historic Site, Fort Sumner, NMMonuments.org; and, Kit Carson Home and Museum, Taos, KitCarsonHomeandMuseum.com

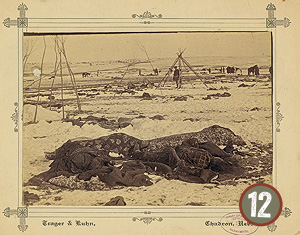

12:: The Battle of Wounded Knee, South Dakota

12:: The Battle of Wounded Knee, South Dakota

Two weeks prior to the battle, Chief Sitting Bull was killed during an attempted arrest by Indian Tribal police. With the Ghost Dance escalating, and numerous armed bands of Sioux , including Spotted Elk’s (Big Foot), converging on the Pine Ridge Lakota Indian Reservation, the Army was sent to de-escalate the rising tensions. The end of the West for many, the Battle of Wounded Knee is the nadir of the American Indian wars with the Northern Plains tribes. On December 29, 1890, on a freezing winter day (above), under the worst possible conditions, the United States Army, under direction of Col. James Forsyth of the 7th Cavalry, attacked and killed at least 150 Sioux, many of them unarmed as they were tracked down and killed while in flight from the battle. The Wounded Knee Museum in Wall, South Dakota, has brought a new sense of public understanding to this tragic and complex event, but like the battle and massacre itself, the Wounded Knee Memorial to the Indians and soldiers who died that day, is in a a forlorn cemetery on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, and is in great need of respect, attention and understanding

Experience History Today @ Wounded Knee Museum, Wall, South Dakota, WoundedKneeMuseum.org; Akta Lakota Museum and Cultural Center, AktaLakota.STJO.org; and, Indian Museum of North America History, Crazy Horse Memorial, Custer CrazyHorseMemorial.org

13:: Donner Party Disaster, Truckee, California

13:: Donner Party Disaster, Truckee, California

The Donner Party was eager to get to California and they decided to take a new trail, the Hastings Cutoff through Utah rather than follow the traditional trail to Fort Hall or Soda Springs, Idaho Territory, where the trail cut south. With numerous setbacks and internal fighting, getting lost on the trail, and delays on the supposed shortcuts, the doomed emigrant party did not make it to the Sierra’s west of Truckee Meadows (today’s Reno, Nevada) before November. Record snowfall trapped them near Truckee (Donner) Lake for four to five months. Many of the men, women and children who survived, 48 of the 87 who started for California in April, resorted to cannibalism to survive. Today, visitors to Donner Memorial State Park can visit the Emigrant Trail Museum and walk where the

ill-fated emigrants camped near the lake and pass (previous page) that carries their name in remembrance today.

Experience History Today @ Donner Memorial State Park and Emigrant Trail Museum, Truckee, California, Parks.Ca,gov; Nevada Historical Society Museums, Reno and Carson City, Nevada, Museums.NevadaCulture.org; California Trail Interpretive Center, Elko, CaliforniaTrailCenter.org; and, National Frontier Trails Museum, Independence, Missouri, CI.Independence.MO.us

14:: Fort Parker Massacre, Fort Parker, Texas

14:: Fort Parker Massacre, Fort Parker, Texas

The attack on Fort Parker would change Texas, American and Comanche history. With the abduction of Cynthia Parker, future mother of Quanah Parker, the legendary half-white Comanche chief, the massacre’s aftermath reverberates through time as a cultural event that even shaped our imagined understanding of the West with The Searchers, book and movie, loosely based on the historic abductions of white children by the Comanche. When Chief Parker, once the most feared Indian leader on the Texas-Oklahoma frontier, was buried on February 24, 1911 (previous page), more than 2,000 attended his funeral. Buried in finest buckskins, next to his mother’s grave in the cemetery in Cache, Oklahoma, Parker was still only in his early 60s at his death from heart disease. Yet, for many, the Comanche leader’s death at such an early age could easily have been from a broken heart, living and fighting between two cultures most of his life,a captive when he was born, and a captive of the 20th century when he died.

Experience History Today @ Old Fort Parker, Groesbeck, Texas, FortParker.org; Bullock State History Museum, Austin; TheStoryOfTexas.com; Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center, Lawton, Oklahoma, ComancheMuseum.org

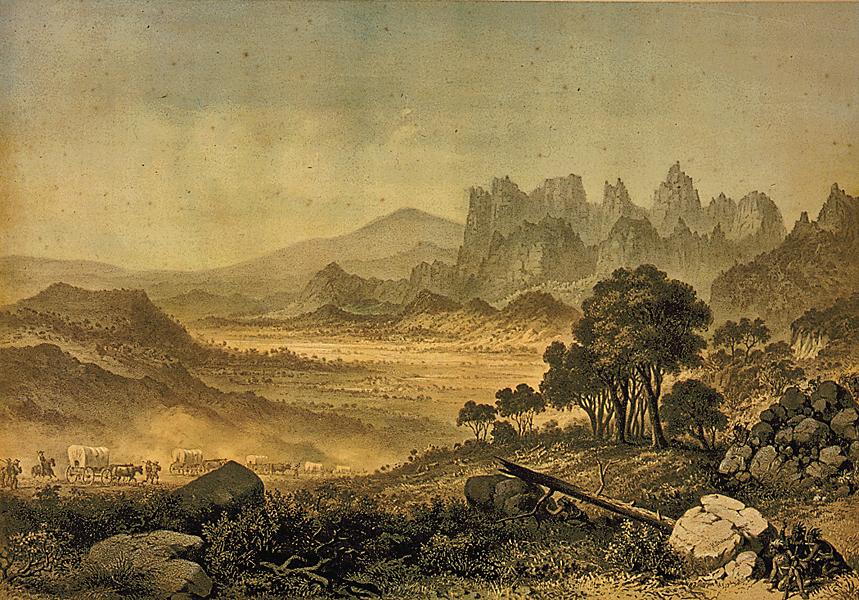

15:: Columbia River Gorge

Traveling on the Columbia River today through placid waters, locks and lakes, the once mighty Columbia is the ultimate result of President Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a northwest passage to the Orient. Visitors to The Dalles, Oregon, the original terminus of the Oregon Trail, who stand along the river bank and watch the barges of grain moving slowly west to ocean going ships in Portland, the nation’s largest inland port, can hardly fathom what the emigrants faced when they reached the Columbia River Gorge (above, circa 1860) in the 1840s. Nor would the ancestors of the indigenous tribes that for thousands of years had fished the salmon for sustenance from famed locations such as now drowned Celilo Falls. TThe tragedy of the Gorge is twofold: the tragic loss of life of settlers and their children who drowned in the rapids of the Columbia, so close to the promised land of the Willamette Valley; and, with the river dammed, the end of a way of life for the local Indian tribes who had lived and fished along the river for hundreds of years. It is guaranteed to make even the stoic weep.

Experience History Today @ Columbia Gorge Discovery Center/Wasco County Historical Museum, The Dalles, Oregon, GorgeDiscovery.org; Oregon Historical Society and Oregon History Museum, Portland, OHS.org; and, Columbia Gorge Interpretive Center Museum, Stevenson, Washington, ColumbiaGorge.org

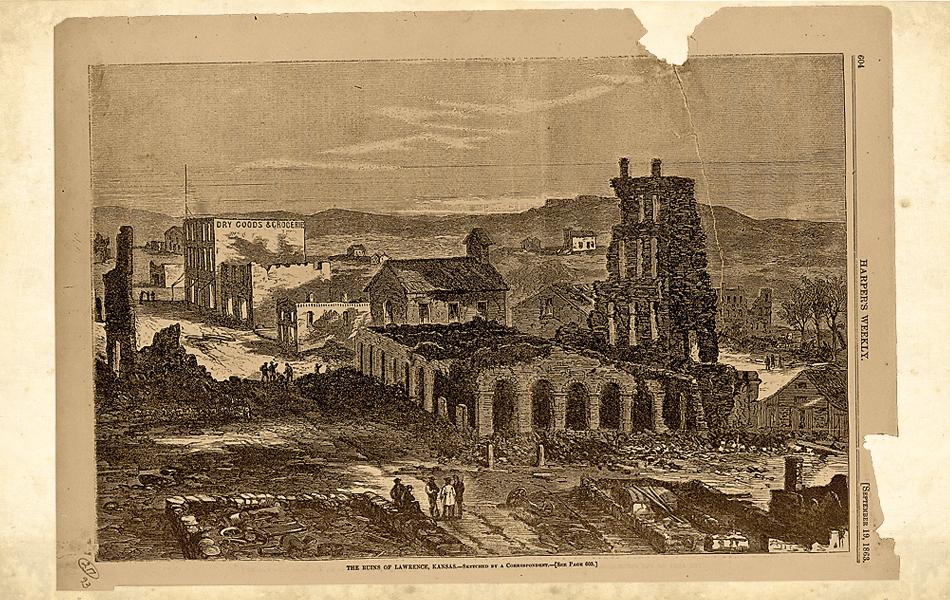

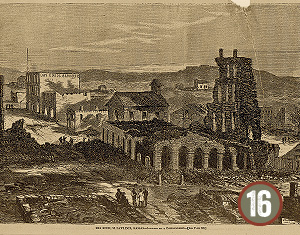

16:: Quantrill’s Raid, Lawrence, Kansas

16:: Quantrill’s Raid, Lawrence, Kansas

The bloody border war between Kansas Jayhawkers and Missouri Red Legs has legendary ramifications, including a rivalry of two states that has lasted more than 150 years, the beginnings of the legend of the James-Younger Gang, and one of the worst American civilian atrocities of the Civil War, Quantrill’s Raid. On August 21, 1863, William Quantrill led a deadly force of guerilla fighters into Lawrence, burning the Kansas city to the ground,

(right) terrorizing the citizens, robbing banks, looting stores, and leaving 185-200 dead men and boys behind. The raid, in retribution for a band of malicious Jayhawkers operating out of Lawrence, and the death of some sisters and daughters of Missouri raiders in a collapsed Kansas City jail, the massacre in Lawrence led to a scorched earth policy in western Missouri, where Kansas Jayhawkers burned out and displaced thousands of Missourians in four counties near the Kansas border. While Quantrill fled to Texas, his bushwhacking force was never the same, and in 1865 he died in Kentucky of battle wounds, but two of his men, Frank and Jesse James would ride on into history.

Experience History Today @ Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas, WatkinsMuseum.org, Historic Lecompton, LecomptonKansas.com; Fort Scott National Historic Site, Fort Scott, NPS.gov; Freedom’s Frontier National Historic Area, multiple locations, Eastern Kansas and Western Missouri, FreedomsFrontier.org

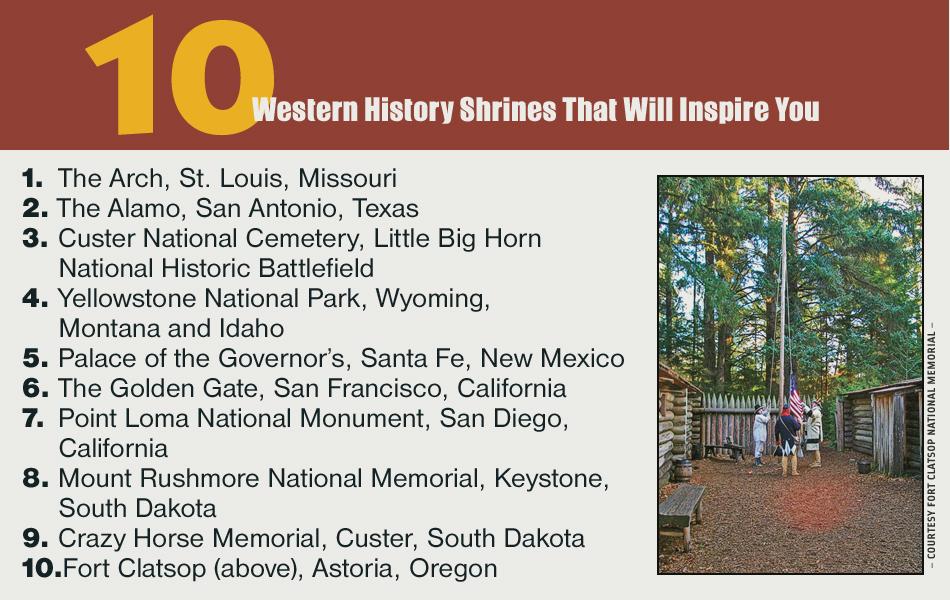

10 Western History Shrines That Will Inspire You

2. The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas

3. Custer National Cemetery, Little Big Horn National Historic Battlefield

4. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, Montana and Idaho

5. Palace of the Governor’s,Santa Fe, New Mexico

6. The Golden Gate, San Francisco, California

7. Point Loma National Monument, San Diego, California

8. Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Keystone, South Dakota

9. Crazy Horse Memorial, Custer, South Dakota

10. Fort Clatsop (above), Astoria, Oregon

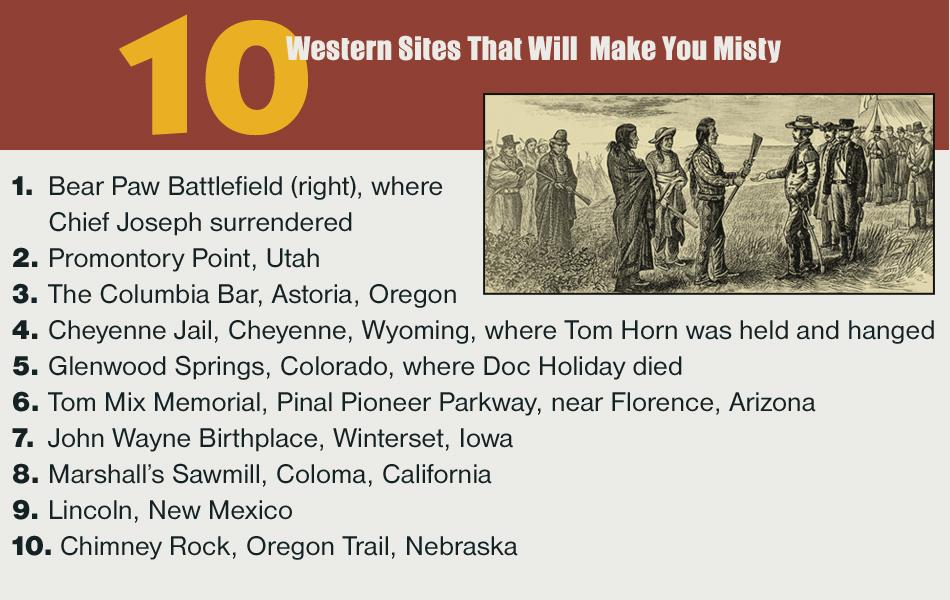

10 Western Sites That Will Make You Misty

1. Bear Paw Battlefield (above),where Chief Joseph surrendered

2. Promontory Point, Utah

3. The Columbia Bar, Astoria, Oregon

4. Cheyenne Jail, Cheyenne,

Wyoming, where Tom Horn was held and hanged

5. Glenwood Springs, Colorado, where Doc Holiday died

6. Tom Mix Memorial, Pinal Pioneer Parkway, near Florence, Arizona

7. John Wayne Birthplace,Winterset, Iowa

8. Marshall’s Sawmill, Coloma, California

9. Lincoln, New Mexico

10. Chimney Rock, Oregon Trail, Nebraska

{jathumbnail off images=”imagesimages/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/bison-at-water-hole_Yellowstone.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/2-Acoma-Pueblo.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/3-john-ross-cherokee-leader.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/4-fort-bowie.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/5-the-alamo.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/6-whitman-massacre.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/7-custer-monument-little-big-horn-1800.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/8-battle-of-washita-ok.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/9-dakota-uprising-MN.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/10-mountain-meadows-massacre.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/11-canyon-de-chelly.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/12-wonded-knee.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/13-donner-party.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/14-fort-parker.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/16-quantrills-raid-KS.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/bison-at-water-hole_Yellowstone.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/2-Acoma-Pueblo.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/3-john-ross-cherokee-leader.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/4-fort-bowie.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/5-the-alamo.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/6-whitman-massacre.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/7-custer-monument-little-big-horn-1800.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/8-battle-of-washita-ok.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/9-dakota-uprising-MN.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/10-mountain-meadows-massacre.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/11-canyon-de-chelly.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/12-wonded-knee.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/13-donner-party.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/14-fort-parker.jpg,images/stories/May-2014/sales-feature/16-quantrills-raid-KS.jpg”}

Photo Gallery

Acoma Pueblo: Acoma Pueblo Battle and Massacre, Acoma, New Mexico

The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas: The War of Texas Independence

Canyon de Chelly, Arizona

Whitman Massacre, Walla Walla, Washington

Columbia River Gorge

– All Historical Photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

Battle of Little Big Horn, Montana

Donner Party Disaster, Truckee, California

Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma: The Trail of Tears

Quantrill’s Raid, Lawrence, Kansas

Dakota Uprising, New Ulm, Minnesota

Battle of Washita, Oklahoma

Mountain Meadows Massacre, Mountain Meadows, Utah

Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Bowie, Arizona: The War with the Chiricahua

Fort Parker Massacre, Fort Parker, Texas

The Battle of Wounded Knee, South Dakota