Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid

“Who remembers Billy the Kid?” Harvey Fergusson wrote in 1925.

Today, everybody does, thanks to Walter Noble Burns’s book the following year, 60-odd movies and countless biographies and novels. We don’t really know where or when he was born, but the trail he left during the Lincoln County War is pretty well documented. By most accounts, he was one charming killer, loyal to his pals, pulled off a legendary jail break, needed a good orthodontist and got killed by Pat Garrett in Fort Sumner in 1881. But would we remember him if he’d been known as Henry Antrim?

Clovis Man

Rambo was a sissy compared to this guy. Some 11,500 years ago (perhaps even longer), Clovis Man went hunting for bison and mammoth, armed with his fluted spears. In 1929, a teenaged boy named Ridgely Whiteman followed in the footsteps of Folsom Man discoverer George McJunkin by finding what became known as the “Clovis Man Site” in Blackwater Draw near the town of Clovis. Hunting a mammoth with a spear? Wow!

Cabeza de Vaca

When Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and several Spaniards were shipwrecked on Galveston Island in 1528, he did what any sensible tourist would do. He left Texas. Historians are divided on the route he took during his eight-year journey, but the stories he heard and told about the legendary golden Seven Cities of Cibola would fuel often-violent Spanish exploration beginning in 1539. Maybe de Vaca should have stayed in Texas.

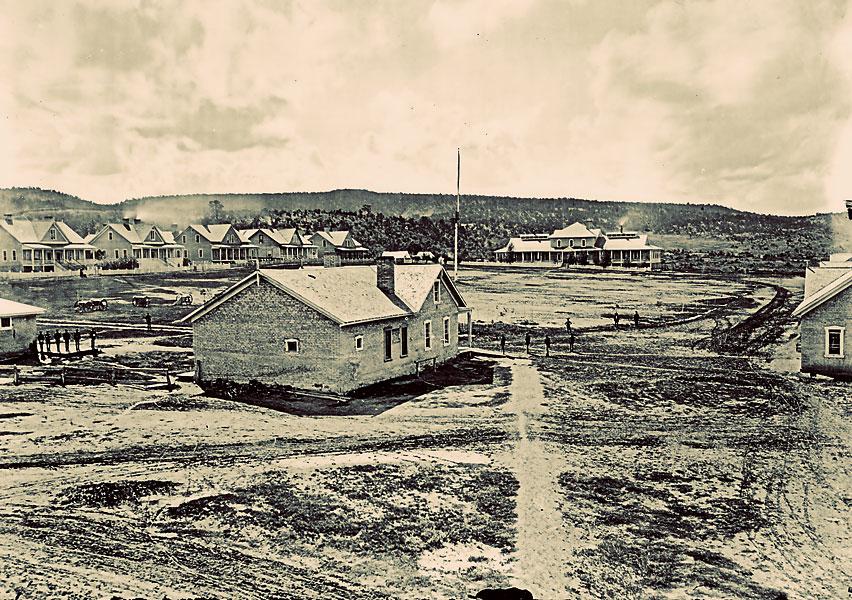

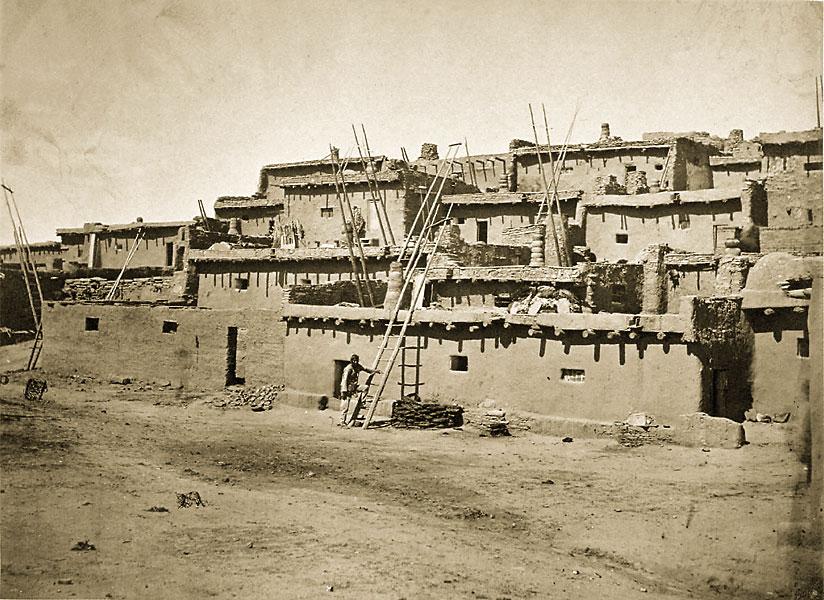

Don Juan de Oñate y Salazar

With a grant from the viceroy (and titles governor and captain general of New Mexico), de Oñate led Spanish colonists into New Mexico in 1598, establishing the first capital near present-day Española. He also chased after those mythical golden cities—with no luck—and is vilified these days because of a violent attack against Acoma Indians.

Pueblo Revolt

By 1680, New Mexico Indians had had enough of Spanish rule. They didn’t care much for having their religion prohibited or being forced into slave labor. So a San Juan Pueblo Indian named Po’pay organized a coordinated Pueblo revolt beginning on August 10. Some 400 Spanish colonists were killed, along with 21 priests, and the Spaniards were driven across the Mexican border. Unfortunately for the Indians, they’d return some 12 years later.

Sibley Invasion

Confederate Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley led an army of Texans into New Mexico in 1862, hoping to claim the Colorado gold fields and, eventually, California ports for the Southern cause. He actually turned Union forces back at Valverde, took Albuquerque and even Santa Fe before limping back to Texas after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. All of this helped persuade Congress to separate New Mexico into two territories, and the Territory of Arizona was born in 1863.

Literary Giants

Say all you want about Richard Bradford (Red Sky at Morning), John Nichols (The Milagro Beanfield War), Eugene Manlove Rhodes (Pasó Por Aquí) or Conrad Richter (The Sea of Grass), but the two novelists who did the most for New Mexico are Ol’ Max Evans (still alive and kickin’ in Albuquerque) and Tony Hillerman (1925-2008). Evans brought the state’s post-WW II cowboy to life in The Rounders and The Hi Lo Country, and helped relaunch the film industry here. Hillerman showcased the Navajo Nation and turned contemporary Indian cops into smart-thinking good guys in novels like Dance Hall of the Dead, A Thief of Time and Skinwalkers. But go figure: Hillerman was a native Oklahoman; Evans was born in Texas. New Mexico also claims Rudolfo Anaya, author of Bless Me, Ultima and the father of contemporary Chicano literature. He’s a native, born in Pastura and still writing in Albuquerque.

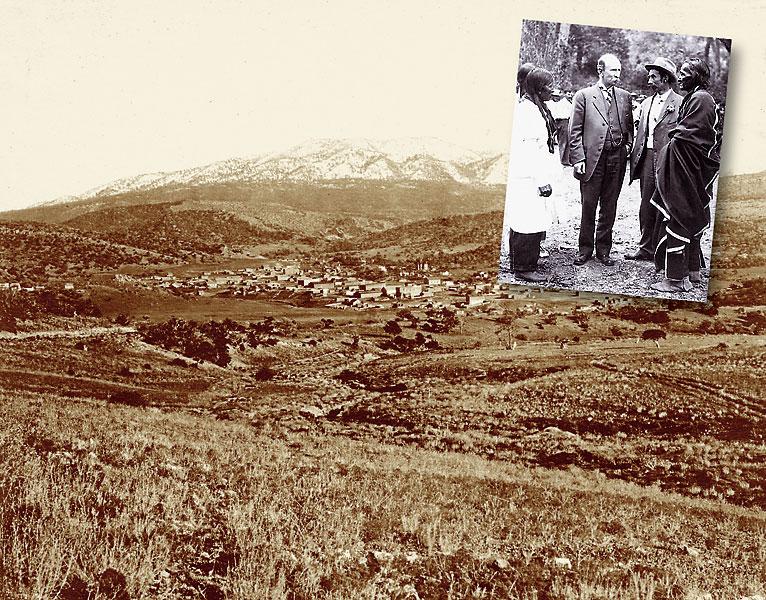

Tourists

There’s no Grand Canyon or oceanfront property, but tourism rocks in the Land of Enchantment. Restaurateur Fred Harvey figured that out in the late 1800s, and back in 1922, Edgar L. Hewitt had Indian artists wear feather bonnets to make white buyers happy at Santa Fe’s first Indian Market. And those Navajo kachinas? Unlike the Hopi’s, Navajo kachinas have no religious significance. They’re for tourists, too. But from Taos to Santa Fe to Lincoln County to the Trinity Site, from art to nature to science to history, there’s a lot to bring tourists to New Mexico.

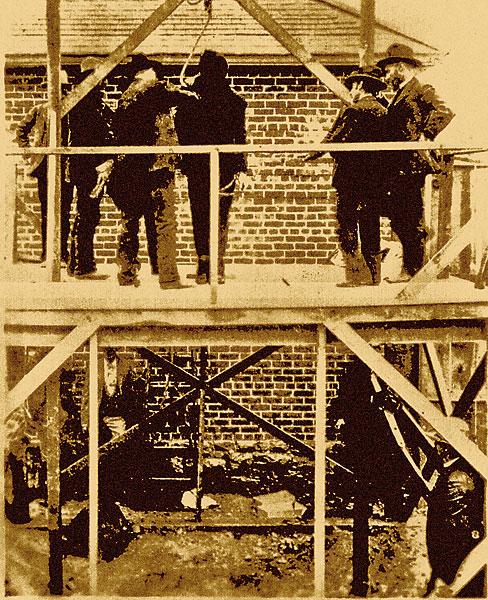

Jerked to Jesus

New Albuquerque’s first town marshal ended up hanged by the townspeople he served! Marshal Milt Yarberry had been the shooter in two questionable killings: the first one took place just one month after he became marshal in February 1881 and the second, in June 1881. He was acquitted in the first trial, but the jury in the second case found self-defense a difficult notion to accept since no gun was found on or near the victim and because Yarberry had shot the man three times—twice in the back. On February 9, 1883, he was hanged at the Bernalillo County Jail in Albuquerque’s Old Town. His hanging was unusual in that the gallows was a new contraption based on plans published in Scientific American. Instead of dropping through a trapdoor, the condemned man was yanked upwards when a 400-pound weight was dropped. In reporting the execution, one newspaper noted that “the soul of Yarberry was wafted to the presence of his Maker.”

No Accident

In the frontier town of Las Vegas, more than one hardcase was removed from jail prior to trial and hanged from the windmill in the Las Vegas plaza. Miguel A. Otero, governor of the New Mexico Territory from 1897-1906, recounts one such incident in his book My Life on the Frontier. Otero reports of a cowboy showing off his pistol-handling skills in Las Vegas in the late 1870s when the pistol discharged and killed a man standing by him. The cowboy said he was sorry, that it was just an accident, and then continued with his pistol twirling. Again the gun discharged, this time killing a woman standing across the street. The cowboy, apparently as polite as he was careless, again apologized and noted that this also was an accident. That did not stop law officers from taking him to jail. The next morning, the cowboy was found hanging from the windmill. The sign on his body read, “This is no accident.”

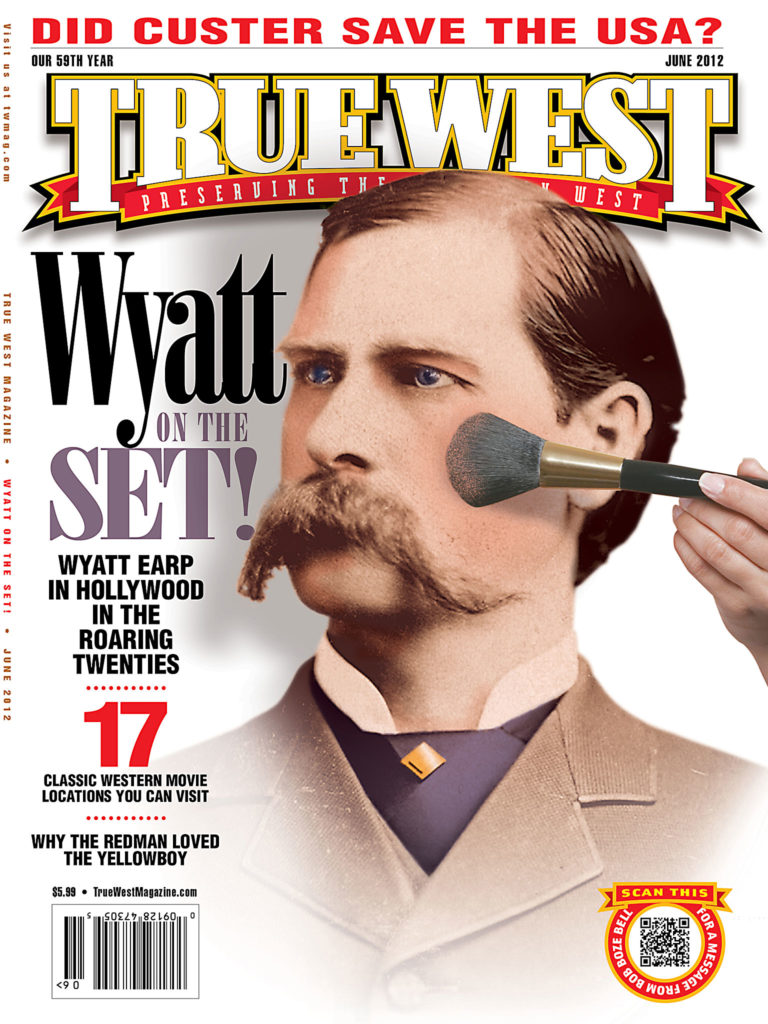

A Healthy Climate for Wyatt

Albuquerque’s sunny, dry climate and clean air has long made the city a destination for people seeking cures for tuberculosis, asthma and other respiratory ailments. In April 1882, one especially colorful party of visitors arrived in Albuquerque by train, looking to avoid a lethal case of lead poisoning. According to the Albuquerque Evening Review, Wyatt and Warren Earp, John H. “Doc” Holliday, Sherman McMasters, Dan Tipton, John “Turkey Creek Jack” Johnson and Jack “Texas Jack” Vermillion spent a week or more in Albuquerque. They were waiting for things to cool down in Arizona following the killing spree the group had embarked on in response to the murder of Morgan Earp, which was, in turn, a consequence of the famous O.K. Corral gunfight in Tombstone.

Lazy S.O.B.

S. Omar Barker, author of novels, stories and verse about the American West, was born June 16, 1894, in a log cabin in Sapello Canyon near New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains. He grew up working cattle in those mountains and took great delight in his Lazy SOB cattle brand, which was derived from his initials. Barker claimed he made more money from “A Cowboy’s Christmas Prayer,” which recounts a humble cowboy’s chat with God at Christmas time, than for any other one thing he wrote. But he didn’t make much off it from Lawrence Welk. The popular band leader wanted to use the poem on his TV show in 1962. Barker said he’d take $100 for it; the show countered with a $50 offer. Barker responded in a telegram that read, “Fifty bucks no steak. Beans. But will accept to help TV poor folks.” After all that, the Welk show apparently decided not to air the poem on the TV program.

Aubry’s Ride

Francis X. Aubry found success in the Santa Fe trade in the late 1840s and went on to blaze new commercial routes into Mexico and across Texas and eventually between New Mexico and San Francisco. But he is probably best remembered for a record-breaking ride he made in 1848. Aubry made a bet that he could ride a relay of horses between Santa Fe and Independence, Missouri, a distance of 780 miles, in six days. That was unheard of, so Aubry’s bet had a lot of takers. He left Santa Fe on September 12, 1848, riding his yellow mare Dolly and leading several other horses. During his gallop, he endured 24 hours of persistent rain, swelling rivers and a lot of mud, but he made it to Independence on the night of September 17, five days and 16 hours after he had left Santa Fe. The ride reportedly earned him $20,000 in collected bets and the nicknames of “Telegraph Aubry” and “Skimmer of the Plains.” Aubry’s ride on this earth would not last long however; he was killed in a saloon fight in Santa Fe in 1854. Aubry was not yet 30.

Readin’, Writin’ & Ridin’

Eugene Manlove Rhodes was born in Nebraska, but in 1881, when Rhodes was 12, he moved with his parents to Engle, New Mexico, where he became a cowboy and later a writer noted for his skill in portraying cowboy life. Rhodes wrote poetry, 10 novels and more than 60 short stories and novelettes, including Pasó Por Aquí (He Passed This Way), about an outlaw who gives up his chance to escape so he can care for a sick family. But before he started writing, Rhodes was first a dedicated reader. He was once reading in the saddle when his horse spooked, went loco and jumped into a deep ravine. When the other cowhands reached him, they found both Rhodes and the horse bruised and bloodied. “Hurt pretty bad?” one of the cowboys asked. “No,” Rhodes said, “But dammit, I lost my place in the story.”

A Shot in the Dark

One of New Mexico’s most notorious unsolved crimes is the November 26, 1904, killing of Col. J. Francisco Chaves in the tiny Torrance County village of Pinos Wells. Chaves was a stockman, a prominent Valencia County Republican and one of the most powerful politicians in the New Mexico Territory. He was visiting Pinos Wells, eating dinner at the home of a local merchant, when a shot fired through the window pierced his heart. The only clues found were the assassin’s footprints that led from the window to a corral where the killer had left his getaway horse. Suspects included cattle rustlers and rival politicians. One man was arrested and confessed to the killing every time he was strung up by his thumbs during questioning. But he took back his confession every time he was let down. So, no one was ever convicted of the crime.

Bunk Mates

Ben Lilly, the bearded, ragged, reclusive hunter who practiced predator control in New Mexico from 1911 to the late 1920s, is estimated to have killed 250 bears and 500 mountain lions. But he apparently got along better with other critters. “I found a snake in my bed yesterday evening,” Lilly noted in a 1931 letter written in Mimbres, New Mexico, and mailed to a daughter in Denton, Texas. “I let it stay all night.”

Finding St. Vrain

In his day mountain man Ceran St. Vrain—one of the founders of the famous Bent’s Fort trading compound in Colorado—was one of New Mexico’s most prominent citizens. He counted Kit Carson among his good friends. When he died in Mora, at the age of 68 in October 1870, more than 2,000 people attended his funeral, considered, at the time, one of the most impressive ever held in New Mexico. Now he is scarcely remembered, and you practically need Special Forces training to find and get to his grave. If you want to pay your respects, go to the Mora Presbyterian Church Cemetery south of Mora, look west until you pick out a flash of white on a small hill about a quarter mile away. Start that way, get over or around three fences, cross a cow pasture—watch where you put your feet—and climb up a steep hill. St. Vrain’s white, marble tombstone stands on top of the hill among several other markers.

Saddle Dandy

Charlie Siringo, trail driver, Pinkerton detective and author of A Texas Cowboy: Or, Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony, was born in Matagorda County, Texas, in 1855, but he retired to his Sunny Slope Ranch near Santa Fe in 1907. He wrote his second book here, about his life as a Pinkerton detective, published in 1912 in two parts: A Cowboy Detective and Further Adventures of a Cowboy Detective. He went on to track cattle rustlers as a mounted lawman.

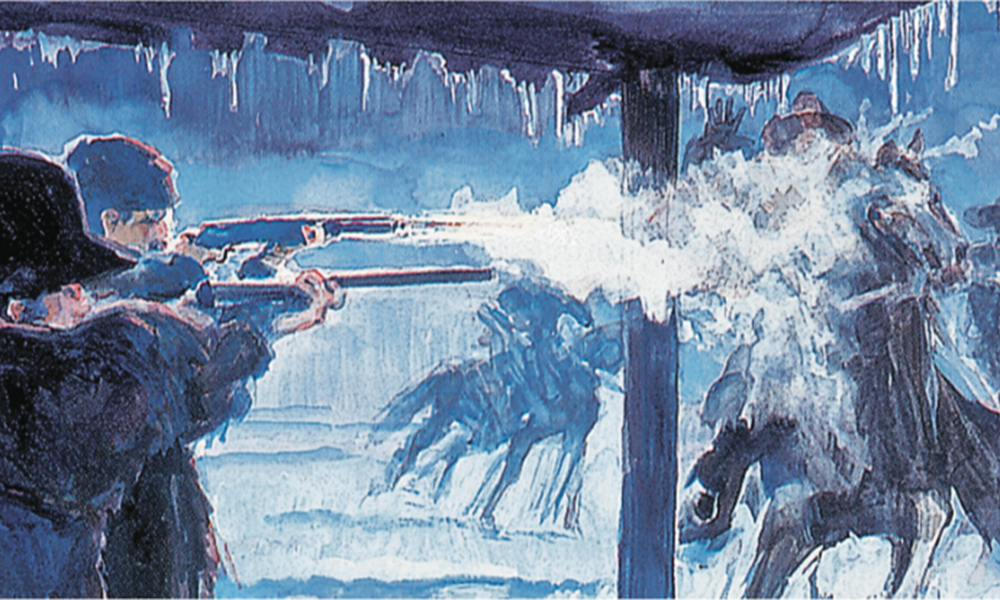

Good Name, Bad Man

The Davy Crockett we all know from history, movies, the Walt Disney TV shows and the ballad would die a hero’s death in March 1836 at the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. But another Davy Crockett, the grandson, or, according to some, the great-nephew of the Alamo hero, died a bully’s death in September 1876 in Cimarron. This Davy Crockett, just 23 in 1876, was ranching in the Cimarron area when he got mean drunk on March 24, 1876, shooting and killing three black cavalry soldiers and wounding another at the St. James Hotel bar. He was acquitted of the crime because he had been drunk. Getting away with murder made Crockett cocky and even meaner. He and his ranch foreman were soon terrorizing Cimarron citizens, including the sheriff, at gunpoint. The mortified sheriff deputized the Cimarron postmaster and an area rancher, and on a September 1876 night, the three men confronted Crockett and his foreman. The rancher-deputy pointed his double-barreled shotgun at Crockett and the foreman and told them to raise their hands. Crockett laughed, and told the deputy to shoot. He did. So did the sheriff and the other deputy. They had to pry this Davy Crockett off his horse. His hands were locked in a death grip on the saddle horn.

Nine Lives

In October 1884, Elfego Baca, a 19-year-old store clerk in Socorro, was enraged by stories about Anglo cowboys abusing the Hispanic residents of neighboring San Francisco Plaza (now Reserve). Baca went to San Francisco Plaza and presented himself as a Socorro County deputy sheriff, which may or, more likely, may not have been true. Whatever the case, Baca arrested a cowboy for illegally discharging his pistol, which led to a gunfight between Baca and some cowboys. One cowboy was wounded and another fatally injured when his horse, spooked by the gunfire, fell on him. Then an angry mob of cowboys (reported numbers range from 20 to 80) went after Baca, who took cover in a hut made of mud and poles and dirt. One cowboy tried to kick the door down, but Baca put two bullets into his stomach, mortally wounding the man. For 33 hours, the cowboys poured hundreds (some accounts say thousands) of bullets into the hut. Baca didn’t even get nicked. A Socorro County deputy sheriff, a real one, showed up, arranged a truce and got Baca out of his tight spot. Baca was tried twice for murder, once for each of the cowboys killed in the fight, but acquitted both times. Baca went on to become a lawyer, a detective, mayor of Socorro, a district attorney, a sheriff, school superintendent, a folk hero and the subject of a 1958 Disney TV mini series titled The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca.

Vanished

Col. Albert J. Fountain, investigator and prosecuting attorney for the Southeastern New Mexico Stock Growers’ Association, and his eight-year-old son, Henry, were last seen on February 1, 1896, as they traveled by buckboard near White Sands in southern New Mexico. Father and son were returning to their home in Mesilla, from Lincoln, where Fountain had secured 32 indictments for cattle rustling and brand altering during a session of the grand jury. A mail stage driver the Fountains met and talked with on February 1 reported that the colonel had been concerned about three mounted men following him at a distance. When Fountain and his son failed to arrive at home, the search was on. A posse found a pool of dried blood and a bloody handkerchief where the Fountains’ buckboard tracks left the road. They later found the buckboard with the colonel’s necktie knotted to a wheel, some of his papers strewn about the ground and young Henry’s hat. Fountain and his son were presumed to have been murdered by cattle rustlers. Two men charged in the case and tried in Hillsboro were acquitted. No trace of the colonel and his son have ever been found.

What Happened to Little Charley?

In March 1883, two dozen Chiricahua Apaches, led by Chatto, attacked Judge H.C. McComas of Silver City, his wife, Juniata, and their six-year-old son, Charley, as the family traveled in a buckboard on the Lordsburg Road, south of Silver City. The judge was riddled with bullets, and his wife was bludgeoned to death. The Chiricahuas abducted little Charley. Some believe the Chiricahuas killed Charley when Apache scouts, under the command of Gen. George Crook, attacked the raiders in the Sierra Madre of old Mexico. But the boy’s body was never found. Newspaper stories suggested Charley may have been the white man seen raiding with maverick Apaches in Mexico and Arizona in the 1920s. Not much to hang that theory on, however. More credible is the suggestion that the Chiricahuas paid a heavy price for the McComas attack. Some believe that the McComas killings may have been the reason why the Chiricahus were harshly treated when Apache Wars ended in 1886. All the Chiricahuas—peace-abiding reservation dwellers as well as death-dealing hostiles, even Chiricahuas who had served the U.S. Army as scouts—were sent to prison in Florida and later Oklahoma. And Chatto? Instead of being hanged for the McComas killings, he was allowed to join the U.S. Army as a scout the year after the attack. But he, too, was imprisoned in Florida and Oklahoma and later settled on the Mescalero Reservation.

Rock of Ages

El Morro, or Inscription Rock, is a 200-foot-high hunk of sandstone, 37 miles southwest of Grants, into which Indians were cutting their symbols hundreds of years before Columbus was born. Later, Spanish explorers and missionaries, and U.S. soldiers and pioneers carved their names and messages here. A sentence attributed to Don Juan de Oñate, the first governor of New Mexico, was carved here on April 16, 1605. A Spanish officer on an inspection tour of Indian Pueblos carved the following: “The 14th of July 1736 passed by here the General Juan Paez Hurtado, official visitor.” That would not be so special if the following had not been added below it in a different hand. “And in his company, the Corporal Joseph Truxillo.” It makes you wonder if Gen. Hurtado had seen the corporal’s addition. Do you think they had KP duty back then?

Victorio Gets Buffaloed

When Victorio got word that he and his people were to be sent to San Carlos Reservation in southeastern Arizona, the chief and his Chiricahua Apache followers took to the hills. Not long afterwards, Victorio and 150 of his warriors attacked a detachment of the 9th Cavalry, killing eight of the black troopers. In May 1880, when Sgt. George Jordan of Company K, 9th Cavalry, heard about an impending raid by Victorio and 150 of his band, Jordan headed with merely 25 troops to defend Tularosa. While fighting the Apaches, were Jordan and his men thinking of their eight comrades killed so recently by Victorio’s Apaches? After Jordan’s troops inflicted several casualties on the much-larger Apache force, Victorio and his men withdrew. Jordan, 32, stood just five feet four and a half inches tall, but he was long on courage (for bravery under fire at Tularosa, he was presented the Medal of Honor, the United States’ highest military decoration). Victorio lived until only that October, when he died at the hands of Mexican Army soldiers led by Mauricio Corredor (or by falling on his knife, as historian Eve Ball believed).

A Vat Way to Go

On August 30, 1912, the body of Solomon Luna was found floating in a sheep-dipping vat on his ranch 75 miles west of Magdalena in Socorro County. His body was nearly unrecognizable because it had been so badly burned by the lime solution in the vat. Luna, a staunch Republican born in 1858, was as responsible as anyone, and more so than most, for New Mexico achieving statehood slightly more than eight months before his death. Luna had served 16 years as Republican National Committeeman from the New Mexico Territory and was a delegate to the New Mexico Constitutional Convention in 1910. The state’s constitution—or much of it—was apparently written in Los Lunas, at Luna’s home, the Luna Mansion (now a popular restaurant). By simply lifting a finger or raising an eyebrow whenever he heard a phrase or clause he did not like, Luna shaped the state constitution. When he died, newspaper accounts touted Luna as the biggest individual owner of sheep in the Southwest and as the richest man in New Mexico. So how did such a powerful man end up dead in a sheep vat? Not surprisingly, foul play was at first suspected. Later, it was determined that he fell into the vat after suffering a heart attack or a stroke.

Lost Gold P.O.

One of the great lost treasure stories of the Old West is the legend of the Adams Diggings, supposedly named for one of the men who was led, in 1864, to a Southwest canyon where you could pick up gold nuggets like so many acorns beneath an oak tree. The gold had been lost when Apaches attacked the men, killing all but three of them—Adams, Jack Davidson and John Brewer. Adams—his first name, like the gold, is lost—went looking for the gold in the late 1870s. A lot of people believe the lost gold is in an area taken up mostly by New Mexico’s Catron County and a section of Grant County north of Silver City. Prospectors, leading donkeys and living in the open, continued to comb that area from the 1920s up to the start of WWII. So prevalent were stories of the lost gold in those parts of New Mexico that a post office and a school were both named for the Adams Diggings.

Pike Parties in Old Albuquerque

In 1807, U.S. Army Lt. Zebulon Pike and 22 U.S. soldiers “accidentally” crossed out of U.S. territory and into Spanish territory near San Luis, Colorado. The Americans were intercepted by Spanish troops and taken first to Santa Fe and then on to Chihuahua, Mexico, for questioning before being escorted back to U.S. territory. While en route to Chihuahua, Pike’s party and their Spanish escorts stopped in Old Albuquerque on March 7 for a time Pike would never forget. Pike and his men were entertained by Franciscan priest Ambrosio Guerra in what was probably the rectory of San Felipe de Neri Church. Pike reported of the excellent wines and various dishes of food, and other kinds of dishes too—pretty girls. Pike wrote how Guerra had ordered his “adopted children of the female sex to appear.” These were Indians girls of various tribes, Spanish girls, French girls, even two young girls who appeared to be English and had reportedly been abducted when they were infants. When Father Guerra noted Pike’s attraction to these two, he ordered them to sit on the sofa next to the lieutenant and to embrace him. They did. Could be this was Pike’s peak.

Bad Day for Black Jack

Thomas “Black Jack” Ketchum, a big, tall man with an impressive black handlebar mustache, was hell on trains in New Mexico in the latter days of the 19th century. His luck ran out in August 1899 when he attempted to rob the Colorado & Southern train near Folsom; he was wounded in a shoot-out with a conductor and arrested. Tried in Clayton, he was sentenced to hang under provisions of a new law that imposed the death penalty for “molesting a train.” He was supposed to be hanged on October 5, 1900, but an appeal delayed the execution until April 26, 1901. By that time, Black Jack was ready to get it done. He practically ran to the gallows; his last words were, “Let ’er go, boys. Let ’er go.” Black Jack might not have been in such a hurry had he known what was going to happen next. When the trap door was released, the force of the condemned man’s fall ripped his head from his shoulders. Some people figured that while waiting for the appeal to run its course, Black Jack had put on more weight than the hangman allowed for.

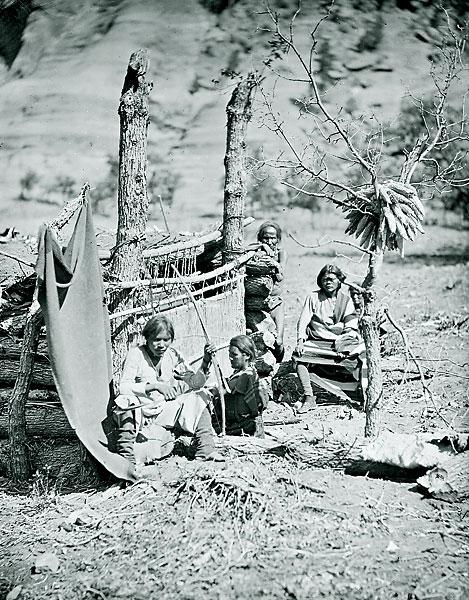

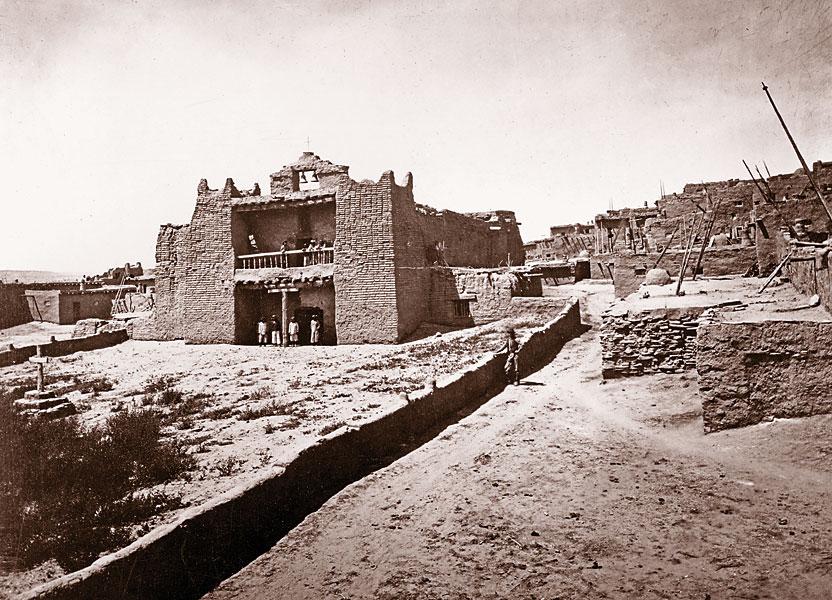

Photo Gallery

Although Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy did his best to replace Spanish Colonial-style churches with European styles after he arrived in Santa Fe in 1850, adobe churches did survive. Children dressed in their Sunday best posed in front of one in today’s Lincoln National Forest in May 1908.

– All images True West Archives –

– McDonald photo courtesy Lincoln County Historical Society/ Lynda Sanchez Collection –