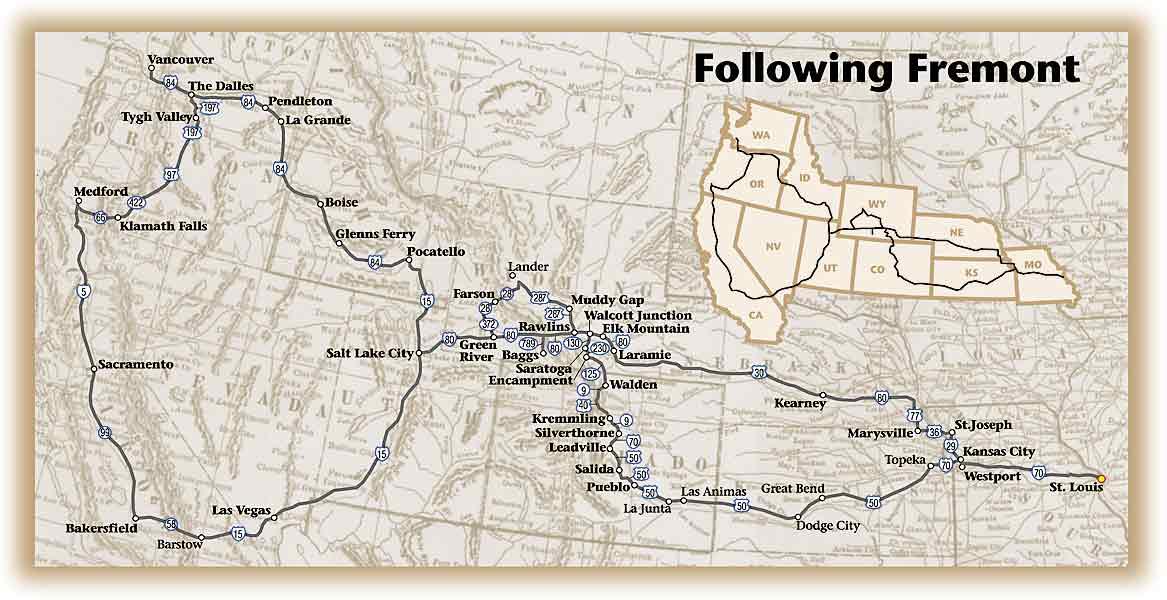

Thousands of overland immigrants to Oregon and California from 1845 to 1849 followed a path first blazed by John C. Fremont.

Thousands of overland immigrants to Oregon and California from 1845 to 1849 followed a path first blazed by John C. Fremont.

After Congress named Fremont to head the survey of the Oregon Trail, Fremont left Washington, D.C., on May 2, 1842, and traveled to St. Louis, Missouri, where he spent nearly three weeks at Chouteau’s Landing, equipping a party that included German cartographer and surveyor Charles Preuss and Kit Carson, the primary guide as Fremont explored the West. This first exploratory trip by Fremont took him over the route of the Oregon Trail, crossing Kansas, Nebraska and entering Wyoming at Fort Laramie, which was then a fur trading post along the North Platte River.

Continuing on the trail the emigrant wagons had begun carving into the landscape, Fremont followed beside the North Platte to the present-day location of Casper, Wyoming, and then struck cross-country to the Sweetwater River, which led him to South Pass. He turned north into the Wind River Range, placing a flag on one high summit that ultimately became Fremont Peak, before returning to the east.

The following year, Fremont headed west again, this time initially guided by mountain man Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick and again accompanied by Preuss, who would collect plant specimens, make topographical sketches and undertake other scientific explorations. Carson was along as well. When Fitzpatrick took some members of the party north along the Oregon Trail, Fremont and Carson crossed into Colorado before turning north into Wyoming.

Jumping Off Point

Just like Fremont chose St. Louis as the optimal place to gather the best men for his exploratory trips, a visit to the Gateway Arch and Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis is the perfect starting point for this journey. Nearby you will find a variety of entertainment and dining options at Laclede’s Landing, located along the river in a former manufacturing district. The namesake, Pierre Laclede, set up his trading post here in 1764. St. Louis-based fur traders were the source of great local wealth, and they helped to make the city a logical starting point for westward exploration, from Lewis and Clark’s expedition of 1804-06 to Fremont’s own groundbreaking journey.

The jumping off point for Fremont’s trip was Westport. From there, strike out for two great history museums that always put me in the mood to travel the country: the National Frontier Trails Museum in Independence and the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City.

When Fremont passed through Nebraska, following the route of the Oregon Trail, he found no significant improvements along the trail. By the close of 1848, the Army would establish Fort Kearny along the Platte River, and the re-created fort is a good waypoint on a modern journey. In addition, you should also tour the Great Platte River Road Archway Monument. If you prefer Fremont’s style of travel, enjoy a hike at Fort Kearny State Recreation Area or a view of the region from the observation tower at Yanney Heritage Park.

Headin’ Into Buffalo Country

Head into my home country by following U.S. 30 west across Nebraska and into Wyoming. Fremont first came into Carbon County, Wyoming, in early August 1843, camping on the principal fork of the Medicine Bow River near an “isolated mountain called the Medicine Butte.” An overnight stay at the Elk Mountain Hotel in Elk Mountain places you at the base of Fremont’s “Medicine Butte.” You’ll find the lifestyle here about as quiet as it was when he was in the region.

On August 3, 1843, Fremont continued west, seeing “bands of buffalo.” That evening Carson “brought into the camp a cow which had the fat on the fleece two inches thick,” which Fremont said “was the first good buffalo meat we had obtained.” His men had traveled 26 miles that day, and the following day hunters brought in “pack animals loaded with fine meat” as the party continued toward the North Platte, reaching the river after nightfall.

With a fresh supply of meat, Fremont camped at the North Platte in the vicinity of what would become the site of Fort Steele. The men were drying the buffalo meat when they were “thrown into a sudden tumult, by a charge from about 70 mounted Indians” who had come over the low hills. The attack came to an abrupt halt when the charging Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians saw the small cannon Fremont had with him. Fremont later wrote the “display of our little howitzer, and our favorable position in the grove certainly saved our horses, and probably ourselves, from their marauding intentions.” Fremont’s camp was a short distance above where Fort Steele was located; you can see photographs and items from the 1868 fort at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins.

On the Road to Oregon

Leaving the North Platte on August 6, Fremont traveled “over an extremely rugged country, barren and uninteresting—nothing to be seen but Artemisia bushes.”

He and his crew turned toward the north and soon reached the Sweetwater River, which they followed over South Pass, taking the “road to Oregon.”

Fremont traveled though the Green River Valley to Bear River, then turned south to Great Salt Lake where he collected plants and rocks as he explored the “waters of the Inland Sea, stretching in still and solitary grandeur far beyond the limit of our vision.”

You can truly learn about the natural wonder of this region at the new Natural History Museum of Utah at the University of Utah’s Rio Tinto Center, which opened last fall. This center interprets the stories ranging from the land of the dinosaurs to native people and the landscape of Utah, including the Great Salt Lake itself. Even the architecture of the building gives you the feeling that you are in some of Utah’s canyonland country.

From Great Salt Lake, Fremont turned north into Idaho, reuniting with Fitzpatrick at the Hudson’s Bay Company post of Fort Hall. You can visit a post replica in Pocatello, Idaho. From Fort Hall, Fitzpatrick and Fremont followed the Oregon Trail to Fort Boise and on into Oregon. Fremont’s 1844 report on this area articulated the concept he had of the Great Basin.

At the Grande Ronde River in northeast Oregon near La Grande, Fremont began following an Indian trail since he wanted to find a “more direct and better road across the Blue mountains.”

He reached the Whitman Mission on October 24. At the Columbia River, he figured he had reached the end of the overland journey from Westport, Missouri, to Oregon Country.

Even so, Fremont continued on land following the south bank of the Columbia River to The Dalles. Here he switched to a canoe, floating the Columbia to Fort Vancouver, where he met with Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin, from whom he obtained provisions in order to continue his travels. Fort Vancouver offers ongoing interpretation of the Hudson’s Bay Company era, as well as details about the early overland travel to Oregon.

After returning to The Dalles, Fremont turned south, passing through Tygh Valley and ultimately around Klamath Lake to cross into California. He traveled through the northern country, crossing the Sierra Nevada to reach Sutter’s Fort at Sacramento, a location that is now a California state park. The fort sponsors regular “hands on history” programs, plus other special events, including a trader’s fair in April.

Fremont continued south across California, traveling through the San Joaquin Valley and then turning northeast along the Old Spanish Trail to reenter the Great Basin and ultimately continue east to the Rocky Mountains. (Two years later, he would be back in California, where he became an important character in the Bear Flag Revolt.)

Sierra Madre Country

On June 11, 1844, Fremont was back in Wyoming, traveling into the Little Snake River Valley. He described the country as “sandy and poor, scantily wooded with cedars, but the river bottoms afforded good pasture.”

The men killed three antelope in the afternoon and camped downstream from the point where Henry Fraeb had engaged in a fight with Indians three years earlier. This was the site of the fight along the Little Snake River with the Arapaho, Cheyenne and Lakota Indians that inspired the names of Battle Mountain and Battle Pass. You can learn more about this fight during a visit to the Little Snake River Museum in Savery.

Although Wyoming Highway 70 crosses the Sierra Madre and keeps you relatively close to Fremont’s route, because of a washout on that road that has not been fully repaired, I instead recommend traveling north on Highway 789 from Baggs to Rawlins, and then taking Highway 130-230 south through Saratoga and Encampment.

Upon leaving the river the following day, Fremont “took our way across the hills, where every hollow had a spring of running water, with good grass.” Ahead of them were the “high mountains which divide the Pacific from the Mississippi waters,” as he put it. “[E]ntering here among the lower spurs, or foot hills of the range, the face of the country began to improve with a magical rapidity…. The country here appeared more variously stocked with game than any part of the Rocky mountains we had visited; and its abundance is owing to the excellent pasturage, and its dangerous character as a war ground.”

On June 13, Fremont moved deeper into the Sierra Madre range, crossing the divide at midday where he noted, “With joy and exultation we saw ourselves once more on the top of the Rocky mountains, and beheld a little stream taking its course towards the rising sun.”

Dropping down the east face of the Sierra Madre Fremont turned south toward “objects worthy to be explored” namely the three parks of Colorado—North, Middle and South. He knew of their existence, no doubt, from information provided by Carson, who had trapped the whole region. That night Fremont’s men again built a fortified camp in a grove of trees where they found plenty of water, grass and game.

On June 14, Fremont tramped southeast along the foot of the mountains. “The country is beautifully watered,” he wrote, adding, “In almost every hollow ran a clear, cool, mountain stream; and in the course of the morning we crossed seventeen, several of them being large creeks, forty to fifty feet wide, with a swift current, and tolerably deep.”

Antelope, elk and buffalo abounded. That night Fremont and his crew camped 10 miles southeast of present-day Encampment, where Fremont wrote, “there were several beaver dams, and many trees recently cut down by the beaver. We gave to this the name of Beaver Dam creek, as now they are becoming sufficiently rare to distinguish by their name the streams on which they are found.”

Moving on south the following day, the men “had an animated chase after a grizzly bear…, which we tried to lasso. [Andreas] Fuentes threw the lasso upon his neck, but it slipped off, and he escaped into the dense thickets of the creek, into which we did not like to venture.”

Fremont’s party continued on through the area the Arapahos called the “Door” because it was an opening they took when traveling to the Colorado Parks. Fremont and his men crossed the Platte River and, as he put it, went “through a gate” in the mountains finding themselves in New Park, known to the Indians as “Cow Lodge” and today known as North Park.

Fremont then crossed Colorado, traveling through the area around today’s Walden, before striking the Arkansas River and following it through Pueblo to strike the Santa Fe Trail. He headed back east, where he reached St. Louis, Missouri, on August 6, 1844. He had finished his 14-month reconnaissance of the West that earned him recognition as the “Pathfinder,” even though he had blazed that trail under the guidance of Kit Carson, Broken Hand Fitzpatrick and other trappers.

Candy Moulton is the author of Roadside History of Wyoming and Roadside History of Colorado.

Good Eats & Sleeps

- Best Grub: Filling Station (Lee’s Summit, MO)

- Hibachi Japanese Steak House (Kansas City, MO)

- Thunderhead Brewing Company (Kearney, NE)

- 17 Ranch Winery (Lewellen, NE);

- Hotel Wolf Restaurant (Saratoga, WY)

- Bella’s Bistro (Saratoga, WY)

- Su Casa (Sinclair, WY)

- Red Iguana (Salt Lake City, UT)

- Cousins (The Dalles, OR)

- Carol’s Corner Café (Vancouver, WA)

- Café Bernardo (Sacramento, CA)

- Best Lodging: Hampton Inn (Kearney, NE)

- Elk Mountain Hotel (Elk Mountain, WY)

- Hotel Wolf (Saratoga, WY)

- Hood House B&B Inn (Saratoga, WY)

- Spirit West River Lodge (Riverside, WY)

- Hotel 43 (Boise, ID)

- Embassy Suites Riverfront Promenade (Sacramento, CA)

</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted; Fremont & Carson photo True West Archives –

– By Steve Moulton –