Mountain Man Hugh Glass was a larger-than-life character in a stage filled with an ensemble of compelling players. His legendary status in the annals of the fur trade era is not due to his exceptional mountaineering and trapping skills nor his ability to recount the essence of blazing the trails that opened the frontier West.

His fame comes from a violent encounter with a grizzly bear and the series of events set off in its aftermath. The ultimate survivor, Glass raised the mountain man’s renowned toughness to another level.

As with most legends, differentiating the history from the myth can be difficult. In his writings on Glass, historian Aubrey L. Haines was forced to introduce elements of the tale with phrases such as, “As the story goes.” Little in the way of direct supporting documentation for the saga of Glass has survived. Glass was literate, as shown by a rare surviving document in the form of a well-penned letter by Glass to inform a father of the death of his son. Glass left behind no written account of his famous bear wrestle, but others who knew him did, and their accounts inform our historical understanding of his survival tale.

Glass had not always been a mountaineer. He was a sailor captured by one of the crews of infamous pirate Jean Lafitte, the “Gentleman Pirate of Barataria.” In order to be spared execution, the unfortunate Glass was forced to embark upon a career as a non-governmental privateer. Pirate life was not palatable to Glass. He and a shipmate reportedly jumped ship off the Texas coast and swam to shore.

The two former pirates struck a course inland, but later were captured by Indians, thought to be Pawnees. Proving himself a difficult man to kill, Glass avoided being burned to death by his captors, as was his less-fortunate shipmate, by offering a gift of vermilion to an important person in the tribe. Accepted into his captors’ tribe, Glass learned their language, tracking, hunting and survival skills. The Pawnees taught him how to navigate without a compass, cross swollen rivers, collect edible plants, start fires and a host of tricks that would serve him well as a mountaineer. In 1822 the tribe traded in St. Louis, Missouri, and Glass took this opportunity to escape.

The next year, Glass got wind of Gen. William Ashley’s famous Missouri Republican advertisement, calling for 100 hardy souls to join him and ascend the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains. Glass signed on to a cohort of mountaineers, who included Jim Bridger, James Clyman, Edward Rose, Jedediah Smith and William Sublette.

Ashley’s expedition had a run of bad luck, losing a trade barge and much of its expensive cargo. A fierce combat with the Arikaras left between 13 and 15 of “Ashley’s Hundred” dead and another nine to 11 wounded, the latter of which included Glass. This battle was the catalyst for Glass to pen a letter to Johnson Gardner of Virginia to inform him that his son John had been killed.

Ashley attempted to mount a punitive expedition against the Arikaras, but his efforts further reduced the size of his expedition to roughly 80 men willing to hazard their lives by going forward. Major Andrew Henry led a group, including Glass, overland via the Grand River. On this leg of the expedition, events occurred that transformed Glass from a lucky freebooter to a legend of survival.

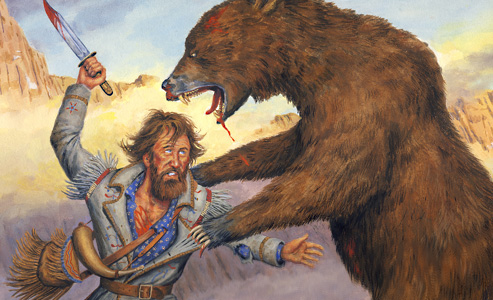

Historically, encounters between bears and humans were fraught with dangers for both. With the average male grizzly weighing roughly 800 pounds and possessing a bite capable of breaking cast iron, a bear was nothing to trifle with. Next to humans, the bear was the most dangerous animal found in the Missouri River drainage. Added to its substantial biting power, a bear could outrun a horse in a short sprint and had forepaws with sharp claws to easily rip a human limb-from-limb. Bears were ravenous and ferocious omnivores capable of bringing down a mounted man and his horse, and feasting on both to satisfy its need to consume roughly 20,000 calories per day (that need matches the caloric value of roughly 48 six-ounce top sirloin steaks).

No eyewitness accounts of the meeting between Glass and his bear have survived. James Hall first shared the story two years after the attack. Expedition member James Clyman recorded an account in his diary years after the event. Clyman’s entry contained the disclaimer, “This I have from information, not being present.”

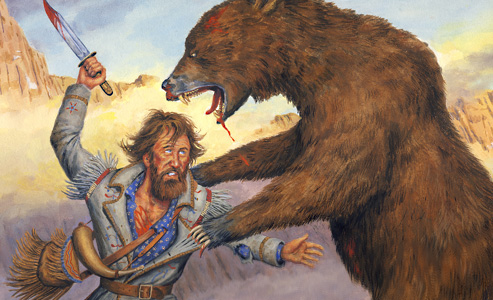

According to the account set down by Clyman, Glass, as was his custom, wandered away from the remainder of the party when he encountered a “large grizzly bear.” Glass fired a shot from his rifle, which hit the bear and enraged the animal. As the mountain man scrambled to climb to safe haven in the boughs of a tree, the rampaging bear pulled Glass down to the ground and severely mauled him. The noise generated by the encounter brought other members of the party to the rescue. With the animal so close to their wounded compatriot, the rescuers were hesitant to shoot for fear of hitting Glass.

“At length the [bear appeared] to be satisfied and turned to leave, when 2 or 3 men fired,” Clyman wrote. “The bear turned immediately on Glass, and [gave] him a second mutilation.”

Glass had survived two savage maulings, but his ordeal was not over. When the bear turned to leave Glass for a second time, the party fired several more shots at the animal. With its dying energies, the bear jumped on Glass for a third time, finally perishing and collapsing upon the wounded mountaineer.

The rescuers were likely surprised to find that, once they removed the corpse of the bear, Glass was alive. He had against all reason survived being bitten and mauled several times and being crushed by an animal over 800 pounds in weight. Any one of these episodes might have killed the mountaineer, but Glass had refused to die.

Examining the extent of Glass’s wounds, which included multiple lacerations and perhaps a broken leg, the mountaineers pronounced the wounds mortal and made preparations for their compatriot’s burial. They dug a shallow grave, and two members of the party, Bridger and John Fitzgerald, remained behind, waiting for their charge to breathe his last. Glass was laid in the trench, and Bridger and Fitzgerald nervously stood their grim vigil.

As the story goes, Bridger and Fitzgerald fretted over being attacked by Indians. Since Glass was not sufficiently compliant to just die, the two decided to cover Glass over with the hide of the bear and get out of there before Indians arrived. Fitzgerald took Glass’s rifle, and the two sped off to rejoin their party. Only Bridger and Fitzgerald would know that Glass was still alive when abandoned, or so they thought.

Glass eventually came to, alone and covered by the heavy, stinking bear hide. He discovered his possessions were gone. He tended his own wounds and made great use of the survival skills taught to him while a captive of the Indians. He decided to head toward the nearest settlement, Fort Kiowa, on the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota, reputed to be roughly 300 miles from where he had met his bear.

Glass rose from his grave and walked into the history books, creating a cottage industry in embellishments of his story. Elements of the spice-enhanced plot have included a revenge theme, a forgiveness theme and have even credited Glass with killing the bear with a knife. Bridger, a man with a long record of changing facts to his advantage, recounted a version of the tale that omitted his and Fitzgerald’s premature abandonment of the seriously wounded Glass. Even in its raw, unvarnished form, the tale borders on the amazing. Though severely wounded, Glass made his way to safety while gathering food and water along the way. He returned to his life as a trapper, apparently none the worse for wear. He reputedly recovered his rifle from Fitzgerald and forgave young Bridger. True or not, Glass did not exact revenge on those who left him to die.

Glass’s amazing adventures continued after his heralded return from the Grand River. He was wounded in a fight with Utes, receiving an arrow in his spine. Glass somehow managed to travel roughly 700 miles with this painful injury before another mountaineer removed the projectile from his backbone.

In the winter of 1832, the amazing survival story of Glass came to an end when his old adversaries, the Arikaras, ambushed his trapping party on the Yellowstone River, killing Glass and two others. This time his rifle was taken from his corpse. That day, the warriors killed the man, but not the legend.

SURVIVAL TIPS:

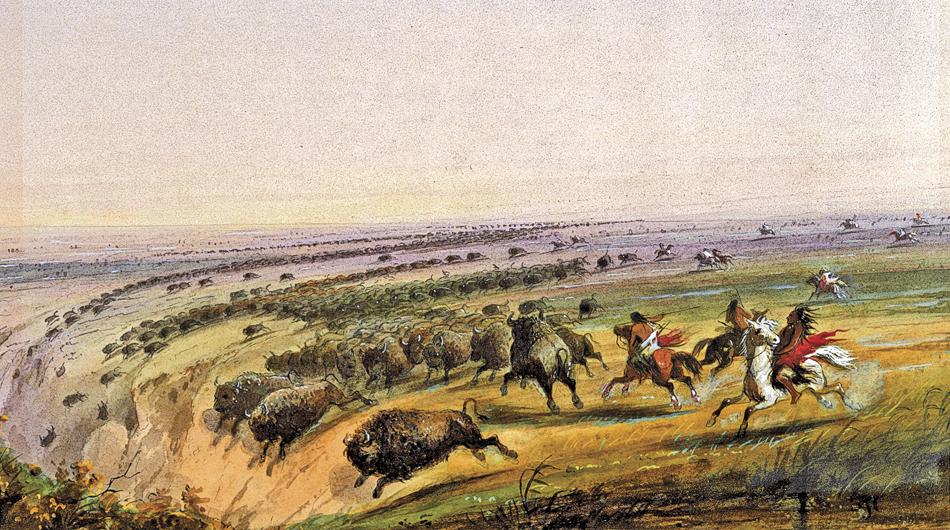

Surviving a Buffalo Stampede

In the late 1980s, I was hiking in Theodore Roosevelt National Park to visit colleagues excavating an archaeological site. My map directed me to the best fording place on a long stretch of the river that ran clear, swift and cold that morning. At the midpoint in my crossing, I heard a strange rumbling, seemingly coming from the opposite side of the river. I did not think much of it until a few seconds later, when a line of buffalo appeared on the terrace above the river.

When the herd is on the move, leaders set the direction for the herd, which proceeds with a picket of male sentinels. The appearance of these giants on the terrace above me was a line of those sentinels. I now noticed the hoof prints scarring the terrace slopes and leading to the very ford where I stood, almost crotch deep in swiftly moving water. The buffalo used this ford a lot. The same vulgarism last recorded in the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger escaped my lips. A herd was coming through this ford any moment, and I needed to be somewhere else before that happened!

As the first of the sentinels began to clatter down the stony slope, my feet took over, and I started slogging toward the opposite bank. My mind was racing, looking for a way out of this. As I got into shallower water, I felt like my cement shoes were gone and I began skipping across the river. Behind me, the lonely clattering of the first sentinel turned into a cacophony of clicking hooves and then splashing. There was that expletive again!

Within a few feet of the water, I spotted a small tree roughly three inches in diameter and possibly 15 feet high. I ran straight for it. I hoped the bushy plume of leaves above the thin trunk would discourage the nearsighted beasts on my tail from going through it. I could hear their heavy breathing between the splashes.

My mind raced for options. Somehow those John Ford images of cowboys waving blankets at stampeding cows popped into my head. Buffalos are a lot like cows, right? It was the only plan I had, so what the heck?

With my back against the side of the tree that was opposite the herd, which was beginning to emerge from the river, I reached for the poncho stuffed in the back of my harness belt and frantically waved the poncho with one arm, while my other arm flailed the air with an empty hand. Just as I started my bizarre gesticulations, the herd, still moving at a swift trot, reached me. The river had not slowed them down. They steered clear of the arm with the flapping poncho, but my empty hand brushed against the woolly hides as these huge animals split around my sheltering tree. I felt like the herd took hours to pass, but I know their stampede was over in a minute or two. The herd was only a few hundred individuals in number. They pulled a hot wind with them, and, in the choking dust, I watched the herd pass over the terrace on my side of the river off to better grazing.

Returning to the ford, I looked and listened carefully before attempting to cross the river again. I pulled a tuft of wiry golden hair off my sleeve and, while examining it, said to myself, “Disney’s got to do this!” Thank you National Park Service for a truly exhilarating day and for giving me a tale to tell around the campfire.

Hugh Glass’s Bear Safety

The best survival tip for dealing with a bear is to not do anything that might enrage the animal. Bears often caution interlopers with displays of their size, warning coughs and false charges. Mighty giants engaging in these behaviors are saying, “Back on out of here, now!” It is wonderful advice.

A frontiersman was truly courageous when he took shots at a bear with a blackpowder weapon, something Hugh Glass had in abundance. A wounded bear could rush and kill its attacker with its last efforts. Shooting at a bear made it angry; the animals are renowned for requiring “a lot of killing” before they finally lay down and die.

Having enraged his bear with his rifle shot, Glass attempted another effective technique to avoid bears by climbing a tree. Adult bears are too heavy to get far up into any but the stoutest of trees. Had Glass been a quicker climber, he might have been just a footnote as one of “Ashley’s Hundred,” instead of a legend.

Feigning death

A common bear attack survival strategy during frontier days was to feign death. If the bear was not hunting a human for food, the animal would abandon the attack. People gave off strong odors offensive to the bear’s sensitive snout; the disgusted bear left behind the smelly human “corpse” and continued on its way.

This was not a successful strategy if the bear was hungry enough or, as in the case of Hugh Glass, something occurred to convince the bear that the attack needed to continue. Glass was either unconscious or playing dead when the bear started to leave him on two occasions. The continued shooting by Glass’s companions, however, extended the conflict each time the bear began to leave.

Man’s best friend

Man’s best friend could be a curse or a blessing in protecting people from bears. Dogs were adept at providing early warning of a bear’s approach. A dog’s marking of territory around a campsite encouraged the bear to forage elsewhere. If this was not heeded, a cacophony of warning barks and yips often effectively turned a bear away.

In the case of a bear attack, dogs sometimes became a crucial part of the defense, using their instinctive pack hunting techniques to harass the bear from multiple directions. The kind of dog that was not prized was the one that enraged a bear away from the camp and brought an angry giant back to its owner. Such a dog was a candidate for the stewpot.