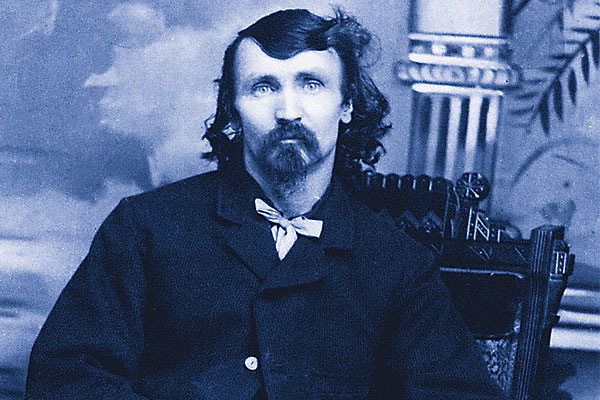

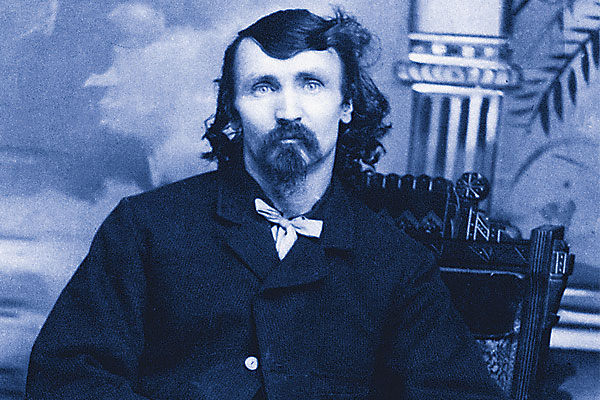

He was a shoemaker, Army veteran, hunter, guide, scout, miner, convict, harness maker, cane carver, horsehair braider, “jack whacker” and, of course, a cannibal.

Which reminds me: The Brick Oven is known for its pizza. If you don’t mind fighting off all those Brigham Young University students, you can find just about every ethnic food around these parts, and you can even get a drink in Utah. Add to that all the natural beauty like Bridal Veil Falls, Cascade Springs and the Provo Canyon Scenic Byway, and you wonder why Alferd (some argue it’s Alfred) Packer ever left Provo, Utah.

He probably wished he hadn’t.

Born on November 21, 1842, in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Packer served briefly in the 16th U.S. Infantry and Eight Iowa Cavalry during the Civil War—discharged for epilepsy—and drifted. Yet his adventures began here in Provo, in 1873.

Gold had been discovered in Summit County, Colorado, and Packer, in need of a grubstake, hired on as a guide to bring a group of prospectors from the comforts of Provo all the way to Breckenridge. Had they known how much ski-lift tickets would cost in Breckenridge, they might have stayed put. They left Provo in late November.

Now, I don’t like to second-guess anyone from the driver’s seat of a Ford Mustang with the heat on, but having lived in the Rockies, having been snowed on in July, having broken ice in my canteen in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest in June, having survived a harrowing ride over Loveland Pass, and having frozen my butt off in Leadville in January, that was one bad idea.

We don’t know how many men actually left Utah, but by the time they reached Colorado, they would go down in history as the Party of 21. Only it wasn’t a party.

Delta Dawn

January found them eating barley they had brought with them for their horses. That’s hard to believe if you venture through Delta when farmers are hawking their fruits from roadside stands or tourists are heading over to Paonia for the Mountain Harvest Festival in September, but it can get downright unpleasant during winter. In 1873, there was no Delta County History Museum, no Fort Uncompahgre Living History Museum, not even Davetos Italian Restaurant, and there probably wouldn’t have been any prospectors alive if Chief Ouray and his Ute Indians hadn’t saved their frozen, starving Utah hides.

Ouray invited the Party of 21 to wait out the winter at his camp, and we all know there’s always a party going on in Montrose.

That’s because there’s plenty to eat in this cool town, from salmon cakes at Café 110 to omelets at Jo Jo’s Windmill Restaurant to the chicken fried steak at the Red Barn Restaurant and Lounge or a mango margarita at Amelias Hacienda Restaurant.

Ouray gets his due at the Ute Indian Museum & Ouray Memorial Park just outside of town. And Packer … he got dinner near Lake City.

Where’s the Beef?

Gold, you see, kept beckoning the prospectors, pulled some of them out of common sense and on to Breckenridge. In February, two groups lit out along the Gunnison River. The first party, of five, made it—barely—to the Los Pinos Indian Agency. The second, led by Packer, had an even harder time. In early April 1874, Packer came down from the mountains and into the agency’s mess hall with a Winchester rifle and burning coals in a coffee pot (to light fires). And the legend began.

It’s a pleasant drive through this part of Colorado. Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park is worth a detour, and Curecanti National Recreation Area sure looks pretty. I’ll get ahead of my story and drive on to Gunnison, where Packer sat in jail for three years, then faced a second trial for what happened down south. Gunnison is home of the Gunnison Pioneer Museum, plenty of Gothic Revival and Queen Anne homes, and Western State College. Yet there was no Gunnison when Packer and his party were in the area. There was no Lake City, neither.

Things are quiet on a crisp morning when I cruise down Highway 149 and into Lake City. The Hinsdale County Museum showcases Mr. Packer, displaying the shackles he wore in jail, buttons from his dinner attire, even a piece of skull from one member of the unfortunate party. It all happened just outside of town—remember, there was no town in 1874—at the Massacre Site, also known as Dead Man’s Gulch and Cannibal Plateau.

It’s cold up here. Lonely. And, darn it, there’s no place to eat!

Packer’s party—Shannon Wilson Bell, James Humphrey, “Butcher Frank” Miller, George “California” Noon and Israel Swan—got big-time lost, ran out of food and then got snowed in. Packer said he returned from a scout to find Bell roasting flesh. Bell, whom Packer said had gone mad, rushed him with a hatchet, and Packer killed him.

Then he ate him. And the others.

What’s a Saguache?

Packer told different stories about what had happened up in the mountains, and as more folks began to suspect him of murder, he wound up jailed in Saguache. The Saguache County Museum also tells the story of the Man-Eater, although I’m not sure that’s such a good idea when the museum opens each Memorial Day with a … uh … barbecue?

Eventually, Packer escaped. He wouldn’t return until he was captured in Wyoming nine years later and brought back to Colorado to stand trial. Area newspaper editors had fun with the story, making The New York Daily News envious of sensationalist phrases and headlines like “the Human Ghoul,” “A CANNIBAL’S CONFESSION” and “HUMAN JERKED BEEF.”

In April 1883, Packer stood trial in Lake City. The state argued Packer had murdered his five companions for profit and food. Packer’s defense attorney said he had killed only Bell, in self-defense, then pigged out to stay alive. The jury was charged on April 12 and returned a guilty verdict the following morning. Judge M.B. Gerry didn’t say, “Damn you, Alferd Packer! There were seven Dimmycrats in Hinsdale County and you ate five of them!” Nor did the judge say: “Packer, you depraved Republican son of a bitch! There were only five Democrats in Hinsdale County and you ate them all!” Gerry did call Packer “a poor, pitiable waif of humanity.” Gerry also sentenced Packer to hang.

Yet Packer got a break. Legal and legislative blundering forced the Colorado Supreme Court to overturn the verdict, and Packer was tried again, this time in Gunnison, where he was arraigned on July 31, 1886, on five charges of manslaughter. The cases were consolidated, and Packer didn’t help himself by cursing his enemies and his previous testimony. Found guilty of manslaughter, he was sentenced to 40 years of hard labor at the state pen in Cañon City.

Jailhouse Rock

At that prison, a guard racks his machine gun while I’m walking to the Museum of Colorado Prisons. Well, that’s what I heard, anyway. He didn’t take a shot at me, although he looked like he really wanted to.

The museum gives Packer a place of honor in one of 32 original cells transformed into exhibits. The Colorado Territorial Penitentiary opened in 1871, the museum (located in the women’s prison built in 1935) started in 1988, but this remains an active medium-security unit with some 800 guests of the state.

By all accounts, the Man-eater, inmate No. 1389, was a model prisoner during his stay at Cañon City. Appeals and pardons were constantly denied until Denver Post reporter Polly Pry began pushing for Packer’s release. On January 7, 1901, outgoing Gov. Charles S. Thomas paroled Packer with the stipulation that he remain in Colorado for the rest of his life. Packer left Cañon City with a new suit, a one-way railroad ticket to Denver and $400. He was a big fan of the Denver Post. (I’m partial to it myself—when my books get nice reviews.)

Denver Postings

Packer spent a few months in Denver, then lived in Littleton, then Sheridan and finally Deer Creek Canyon, where game warden Charles Cash found him ill in July 1906 and took him to Cash’s mother-in-law’s cabin. The Cashes and Mama-in-Law cared for the ailing Packer, who suffered a series of epileptic seizures.

Packer continued to claim he had killed Bell in self-defense. A week before his death, he asked Gov. Henry Buchtel for an unconditional pardon. Buchtel didn’t give Packer a break.

At 6:50 p.m., April 23, 1907, Colorado’s Cannibal died. He’s buried in the Littleton Cemetery. The headstone reads:

Alfred Packer

CO. F.

16 U.S. INF.

But a guy like Packer can’t die. He’s been memorialized in a few books, at least one novel, documentaries, even cookbooks and a musical. Not to mention scientific investigations that maybe (or maybe not) proved Packer wasn’t a murderer, just a hungry survivor.

The trip should end after paying respects in Littleton and taking a jaunt through Denver but, I don’t know, all this investigating has my stomach grumbling, and I hear that the El Canibal burrito at the Alferd Packer Grill up in Boulder is simply to die for.

Johnny D. Boggs wonders just what the hell they were serving at that terrible restaurant in Nebraska that an alleged pal recommended.