The Dalton Gang’s gravesite is not exactly front and center, which is strange when you consider it’s one of the big tourist attractions in Coffeyville, Kansas.

The Dalton Gang’s gravesite is not exactly front and center, which is strange when you consider it’s one of the big tourist attractions in Coffeyville, Kansas.

To find the final resting place of Bob and Grat Dalton, and their compadre Bill Power, you’ve got to go to the very back of Elmwood Cemetery. Near some railroad tracks. Away from the graves of solid citizens, including those of George Cubine and Charles Brown, who died fighting the Dalton Gang on the morning that the outlaws tried to hold up two banks at once.

Bob and Grat are nearly 100 feet from the grave of their older brother, Frank, who died in the line of duty as a lawman in 1887. The boys’ momma put up a tall monument for Frank; she did nothing for the other two, who had broken her heart.

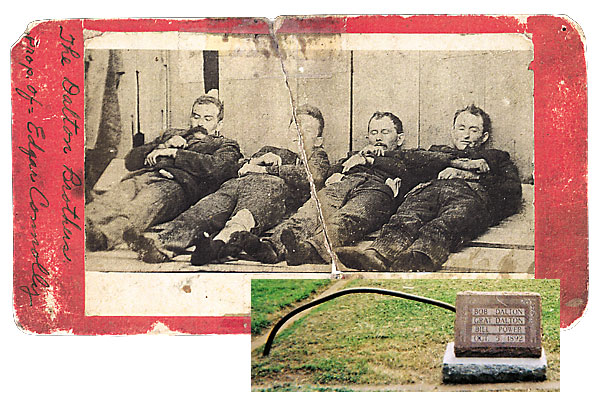

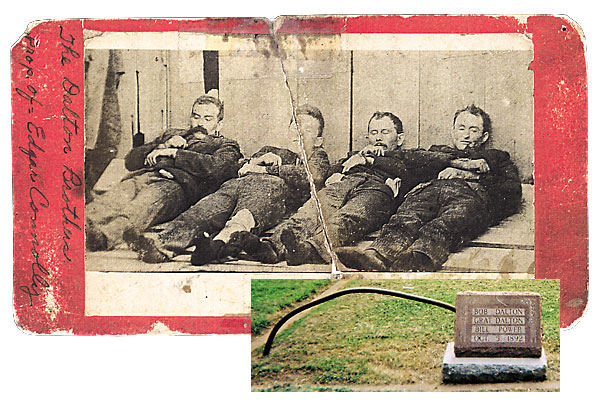

The final straw must have been that raid on October 5, 1892. The carnage from that botched affair included four dead robbers and four dead citizens. The national news catapulted the Daltons into Old West infamy, yet all they got was a single unmarked grave. The other deceased outlaw—Dick Broadwell—at least got his own space in the family plot in another town.

For years, the only thing indicating the gang’s burial site was a bent gas pipe. The cemetery sign states it had been used as a hitching post in Death Alley where the Daltons tied up their horses and walked to the banks.

Not so. Drawings and a photo of the shoot-out scene show the wooden fence where the mounts were tied. The pipe was reportedly scrap found in Death Alley, and its placement at the grave was a sign of disrespect.

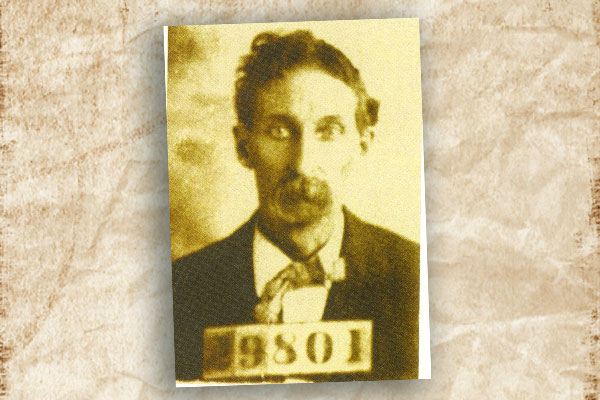

The youngest Dalton brother, Emmett, felt compelled to fix that. The only outlaw survivor of the Coffeyville Raid, Emmett had done his prison time and gone straight, selling real estate in Los Angeles. On April 29, 1931, he and wife Julia visited the scene of the crime.

They claimed to be celebrating a second honeymoon (they had been married in 1908). But Emmett was also peddling his book, When the Daltons Rode. He earned a lot of media attention—especially upon his return to Coffeyville.

During the visit, the ex-hardcase hired a stonecutter to carve a headstone for his associates. It was a simple memorial—just the three names and the death date.

Emmett gave up the ghost in 1937. His widow said he’d be placed with his brothers in Coffeyville. Instead Emmett’s sister, Leona, and an undertaker buried the cremated remains in the family plot in Kingfisher, Oklahoma.

Back in Coffeyville, the headstone was stolen sometime before WWII, say old-timers like John Alvey, who runs the Dalton Defenders Museum. Many locals never knew it was missing. The old scars remained; the citizenry had no desire to visit the grave of killers.

By the late 1960s, tourists flocked to Coffeyville. Folks visited the plaza, one of the banks in the foiled robbery and Death Alley. But when they asked about the Dalton grave, all they got were general directions and a “look for the iron gas pipe” response.

Nearly 30 years after the headstone went missing, the town finally placed a copy at the site. That headstone marked the grave until September 2010, when a tourist reported the 400-pound stone missing. Stolen again?

A search turned up nothing. Then on November 2, a Watco Railroad employee found the headstone near a creek north of Coffeyville. Except for a small chip on the back, it was unharmed.

Nobody has been arrested in the case. Police say it may have been a teenage prank.

Local officials put the stone back—this time super cementing it to the base to prevent future thefts.

The gas pipe is also there, both ends buried in the ground, adding a weird highlight to one of the most famous graves in Old West history.