I knew better than to play cards with historian Mark Dworkin. He had the ultimate poker face.

I knew better than to play cards with historian Mark Dworkin. He had the ultimate poker face.

During a trip to Georgia, several years ago, we had a chance to visit Susan McKey Thomas, Doc Holliday’s cousin. Her father Thomas was Doc’s uncle, but he and Doc were about the same age, so they were close friends as kids. Mark and I were excited to hear some family stories.

When we entered the home, “Ms. Suzie,” a gracious Southern belle of the old school with a kind look in her eyes and a smile on her face, greeted us from a comfortable chair. Then the lady got right to the point: “Are you gentlemen Yankees?”

I was stunned, and I’m sure I showed it. Mark’s poker face gave away nothing. He replied, “I’m from Canada, from Toronto.”

Ms. Suzie was good with that—Canada had aided the Confederacy during its “war of independence.” Then she stared a hole through me (without losing the smile).

“Guilty,” I responded. I stole a glance over at my friend from the Great White North; I thought I saw a tiny grin come to his mouth, but if so, it was brief.

We laughed about that for years.

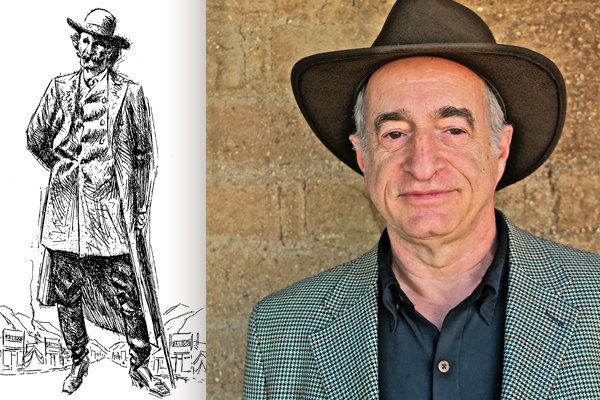

Cancer got the best of Mark Dworkin on August 31, 2012. He was 66. Mark was a gentleman and a gentle man. He treated everyone with respect and courtesy. He unfailingly shared what he had with others (including his research). Those things stick when you’re recalling a man’s legacy.

But as much as anything, Mark was a passionate guy—not that you’d necessarily know it from his placid visage. He had a passion for teaching, for jazz, for his Jewish heritage—and most of all for wife Harriet and his family.

He also had a passion for the Old West, and for Tombstone, which drove Mark to research and explore and write. He loved to discover and recount events and people whom others ignored.

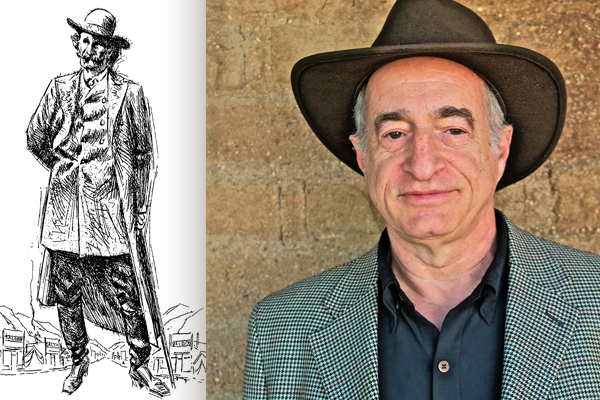

He poured energy into subjects like Wyatt Earp’s various Jewish connections (several friends, third wife Josie and his interment in a Jewish cemetery). He found an illustration, in the Yale library, that may have been of Doc Holliday in the last year or so of his life. He (and colleague Jane Matson Lee) extensively researched H.F. Sills, a mystery visitor to Tombstone who witnessed the O.K. Corral shoot-out in 1881. He also helped find the unmarked grave of Vendetta Rider Dan Tipton in Columbus, Ohio. Working with Peter Brand and others, Mark secured a military marker at Tipton’s last resting place.

But his magnum opus will be his biography of writer Walter Noble Burns. This Chicago journalist turned his pen toward the Old West in the 1920s, writing three essential books: The Saga of Billy the Kid; Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest; and The Robin Hood of El Dorado: The Saga of Joaquin Murrieta, Famous Outlaw of California’s Age of Gold. In many ways, Burns helped create the modern romantic myth of the West, and he made legends of Wyatt Earp, Billy the Kid and others. Burns’s own story is fascinating and shows the lengths he went to in writing his books.

Sadly, Mark won’t be around to enjoy the plaudits for his book. The good news is the University of Oklahoma Press plans to publish American Mythmaker: Walter Noble Burns sometime in 2013.

What I’ve read of the book is great stuff. It is clearly Mark—the poker-faced presentation of facts in a scholarly fashion. But for those of us who knew and loved him, we can see the slight, sly grin behind the words, and remember his sardonic wit.

And his passion. So much passion.