Butch Cassidy is dead. William T. Phillips is dead.

Butch Cassidy is dead. William T. Phillips is dead.

Yet the legend that the two men were one and the same still has not given up the ghost, despite loads of evidence to the contrary.

The most recent reincarnation came last summer, when a Utah book dealer announced he had a manuscript of The Bandit Invincible, Phillips’ autobiography that detailed his alleged life as Butch. A Salt Lake City newspaper ran the story, and the Associated Press sent its version around the world. Media outlets big and small went with it, further spreading the Cassidy/Phillips myth.

Phillips had also spread his tale far and wide. He frequently went to Butch’s old haunts in Wyoming and Colorado, searching for buried loot and outlaw pals. The papers picked up the story by 1936. After Phillips died at a county poor farm near Spokane, Washington, in 1937, the story went away for the next 40 years.

In 1977, Larry Pointer presented his case for Phillips as Cassidy in his book In Search of Butch Cassidy. Much of it was based on The Bandit Invincible.

The Phillips account stated Butch had escaped the Bolivia shoot-out—leaving the dead Sundance Kid behind. He traveled to Paris for plastic surgery to hide his identity. Back stateside, he got married in Michigan in 1908 (the first official record of his existence).

Oh, and he’d had many adventures post-Bolivia—like serving as a sharpshooter for Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution, and prospecting for gold in Alaska (where he said he ran into Wyatt Earp).

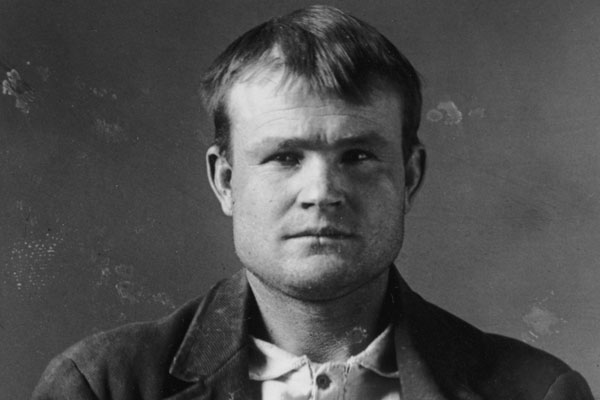

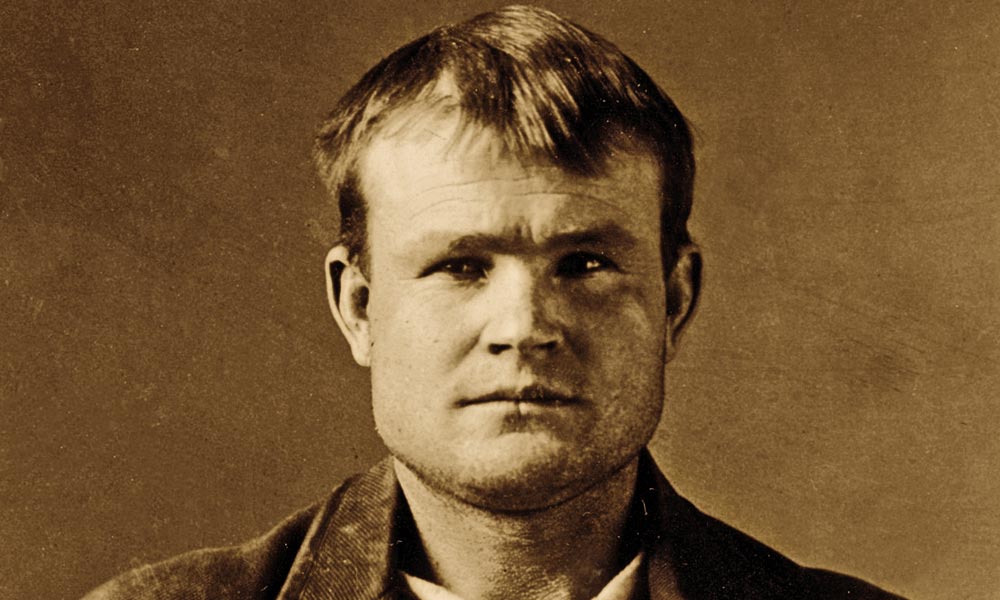

Many people believed. Phillips had an impressive knowledge of Cassidy’s early years, up to and including his stint in the Wyoming state pen in the mid-1890s. Some of the outlaw’s former associates agreed Butch and Bill were one and the same. On the surface, he shared some physical resemblance to the outlaw —both were stocky, had strong, jutting jaws and sported moustaches and devil-may-care grins.

Yet over the last three decades, Wild Bunch researchers Dan Buck and Anne Meadows have uncovered strong evidence disproving Phillips’ claim. Phillips got married in Michigan at the same time Butch and Sundance were demonstrably working in Bolivia. The handwriting analysis of the two men’s correspondence came back inconclusive that the letters had been written by the same man. And Phillips’ knowledge of the South American period was suspect, to say the least. He talked about railroads that weren’t built until after the shoot-out, and he placed the outlaws’ ranch in the wrong part of Patagonia. Plus, most of the Parker clan—including father Maximilian (who lived until 1938) and brother Dan—never accepted Phillips as their long lost kin.

So how the heck did Phillips know so much about Cassidy’s early years?

Wyoming researcher Jack Stroud posited Phillips had served time with Butch at the Wyoming state pen. The mug shot of William T. Wilcox looks much like later photos of Phillips, and reports state Wilcox hung out with Cassidy after the two were released.

So was William T. Wilcox actually William T. Phillips? The only documentary evidence: on his marriage license, Phillips listed his mother as Celia Mudge. Wilcox’s mother was Celia’s sister, Flora.

Pointer, seeing Stroud’s materials, finally decided (after nearly 25 years) that Butch and Phillips were different people. He now believes either Wilcox and Phillips were one and the same or cousins.

That’s how Phillips knew so much about the early Butch.

You need a scorecard to keep track of this “who’s who” puzzle.

But don’t expect this story to die. Very few of the media outlets that spread the Phillips-as-Cassidy myth followed up with Pointer’s admission that they were different guys. Rest assured, William T. Phillips and his claim to be the legendary outlaw will be resurrected again. And again. And again. It’s a tale that seems invincible—unlike the bandit and his wannabe who met their Maker all those many years ago.