It’s official: Everybody wants a piece of Lewis & Clark. Except me.

It’s official: Everybody wants a piece of Lewis & Clark. Except me.

Don’t get me wrong. I appreciate what William Clark and Meriwether Lewis did. I even like the Sacagawea dollar.

But Lewis & Clark don’t rank high with me, not when I’m in Missouri hot on the trail of bad border men like William Quantrill and Bloody Bill Anderson. And I’m certainly not going to buy the Lewis & Clark sarsaparilla that’s being hawked on a local radio station.

Reckon I might as well get used to it. The Corps of Discovery launched its operation on May 14, 1804, so the bicentennial has kicked in and won’t let up until September 23, 2006, the 200th anniversary of the explorers’ return to St. Louis. Museum curators have become nervous wrecks planning all this hoopla.

Practically every place in spitting distance of the Lewis & Clark Trail is opening or expanding exhibits. I begrudgingly concede that St. Joseph’s Wyeth-Tootle Mansion’s L&C exhibit is impressive indeed.

Yet I’m more interested in the Confederate Memorial State Historic Site in Higginsville, a 135-acre park on the grounds of the old Confederate Home of Missouri. Guerrilla Jim Cummins is buried here, and so is William Quantrill, or, rather, parts of him. Everybody wanted a piece of this butcher, so Billy’s also planted in Kentucky, where he was killed, and Ohio, where he was born.

The Kansas-Missouri border-war era just seems so … well, bloodier … than a bunch of wanna-be scientists collecting specimens and drawing maps.

But you can’t escape these dudes.

At Liberty, where the James-Younger Gang began a long career by robbing a bank in 1866, an artist is painting a mural. Not about Jesse and Frank, but the Corps of Discovery.

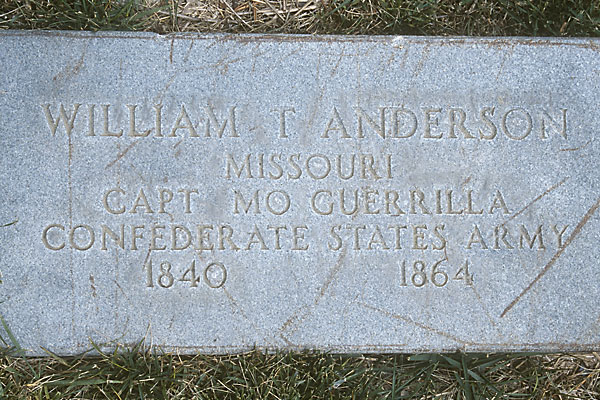

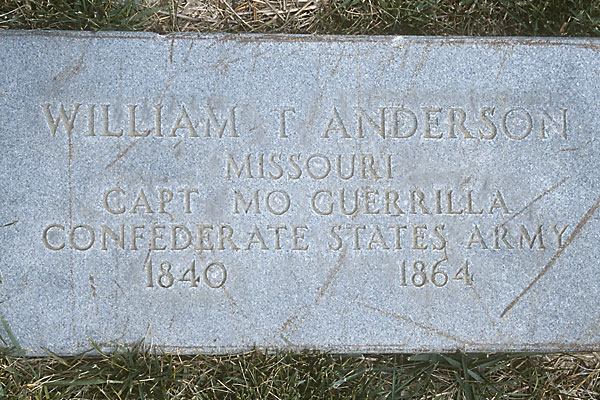

At Richmond, though, I find the grave of Bloody Bill Anderson, a vain, witty, psychopathic killer who had a human scalp braided into his bridle.

Now, I don’t make heroes of Quantrill and Anderson. Truth is, I find them repugnant barbarians, only more fascinating than Captains L&C. Then again, I wouldn’t buy a six-pack of Billy Quantrill sarsaparilla either.

Especially in Lawrence, Kansas.

On August 21, 1863, Quantrill and his men massacred 150 men and boys and left this pro-Union, anti-slavery town in ashes. The Eldridge Hotel was torched—it also suffered a similar fate in 1856—but was rebuilt, and stands tall today (a 1924 version that reopened in 1986). I like Lawrence, its vibrancy and resiliency (except during football season), and no one mentions Lewis or Clark while I’m in town.

I won’t get that reaction in Independence, Missouri. The Jackson County seat, not to mention home of Harry Truman, found itself right smack-dab in the heart of the border wars, which is certainly part of the focus at the 1859 Jail, Marshal’s Home and Museum, but I’ll be bombarded with L&C info when I enter the National Frontier Trails Center.

Yes, the focus of this museum is on the Santa Fe, Oregon and California Trails, and while they may not be selling Lewis & Clark sarsaparilla, they certainly aren’t over-looking the contributions of the Corps of Discovery.

And suddenly I’m struck by how important Lewis & Clark are today.

Kids everywhere are absorbing every-thing they can because of the bicentennial, and I recall seeing children at the other museums touting Meriwether & Will. L&C have sparked our youth. They’re suddenly interested in American history, Western history, and that’s great.

If I had a mug of sarsaparilla, I’d toast the Corps of Discovery for putting American kids on history’s trail. Maybe a few of them will discover the border wars along their journey.

Road warrior Johnny D. Boggs recommends Gates and Sons barbecue in the Kansas City metro area and Free State Brewing Company in Lawrence, Kansas.