In 1949, in an act of profound sagacity uncommon to our normally dysfunctional state legislature, the Roadrunner was designated as the official state bird of New Mexico.

In 1949, in an act of profound sagacity uncommon to our normally dysfunctional state legislature, the Roadrunner was designated as the official state bird of New Mexico.

Now Roadrunner is not a common creature, such as other state birds, like the puny Cactus Wren in New Mexico’s former western province Arizona, or the loud, obnoxious Mockingbird to the east in the former Republic of Texas. Roadrunner is one badass, tough character. (In fact, its bird family is the Cuculidae, which translates in latin as badass—well, not really, but it should).

Roadrunner eats rattlesnakes for lunch and packrats for dinner. Roadrunner loves nothing better than a centipede or scorpion for breakfast. Sometimes Roadrunner snacks on tarantulas. Some of the Pueblo people believe Roadrunner can ward off evil spirits. (Yes, even ghosts fear to tangle with Roadrunner.) Roadrunner can fly, at least for short distances, but chooses not to; why waste energy when no beast dares to challenge you? Coyote flees before Roadrunner (as does my Española-born pit bull mix Colonel Theodore Roosevelt). Roadrunner can make up to 20 miles per hour, using this speed to chase down prey, not to flee from predators. Roadrunner knows nothing of fear. Roadrunner is the perfect state bird for the real New Mexico.

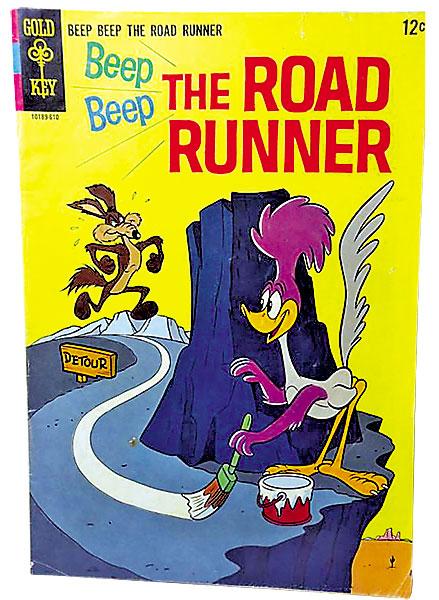

Ironically, also in 1949, cartoonist Chuck Jones created the first of around 50 Roadrunner animated shorts for Warner Brothers. As written by Michael Maltese, Roadrunner engages in a string of high-speed chases and imaginative escapes from his nemesis, one Wile E. Coyote. It is a tale of endless conflict without hope of resolution. Roadrunner is nature, while Coyote is the machine. In fact, Coyote imports all matter of manufactured devices from that wellspring of the Industrial Revolution—the Acme Corporation. He always fails. Roadrunner and his ally, the Southwestern desert, always triumph. Roadrunner is colorful, peaceful, always smiling, always fun loving. Chuck Jones’s Roadrunner is the perfect state bird for the fantasy New Mexico—the Land of Enchantment.

New Mexico is indeed a colorful, majestic and often breathtaking land. There is good reason artists, writers and filmmakers have flocked here for decades. But it is a land of sharp contrast. Beauty masks an arid, unforgiving landscape. Every tree has a thorn, every insect a stinger, every reptile a fang, every animal a claw. A hard land breeds a hard people. In our time they have become an increasingly divided people—the cartoon Roadrunner is the bird of Santa Fe, with its art colonies, literary pretensions, Indian markets, overpriced eateries, swank resorts, crystal gazers and fabulously wealthy part-time residents. Badass Roadrunner is the bird of the rest of New Mexico, with its old-school Hispanic heritage, cowboy mindset, great food in hole-in-the-wall diners, smoke-filled Indian casinos, dog and cock fighting, degrading poverty, unrelenting violence and disturbing drug culture. Many refer to this as the Land of Entrapment.

Ancient Byways

By American standards this is an ancient land. Archaeologists have dated human habitation back 12,000 years (Folsom Man), to be followed by the Anasazi ancestors of the Pueblo tribes that the Spanish would eventually encounter along the Rio Grande. The Anasazi lived in cliff dwellings, which speaks to the precarious nature of their lives. Roadrunner survived, but they didn’t. Eventually climate change or some other calamity crushed their population and split them apart into widely scattered bands.

Some Anasazi settled along the life-giving river that the Spanish would name Rio Grande when they arrived in 1540. Those remarkable shipwrecked adventurers—Cabeza de Vaca, Castillo and Dorantes, along with his black slave Esteban—wandered across the Southwest, certainly visiting the pueblo near the confluence of the Concho and Rio Grande around 1535. They eventually reached Mexico City where Esteban was ordered to guide a Spanish expedition under Fray Marcos de Niza back to the north in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. At Hawikuh, southwest of Zuni, Esteban was killed in 1539 and the Spanish fled back south. Zuni tradition holds that he was killed over his advances toward their women, a story confirmed by Fray Marcos. Alas, poor Esteban, probably not the first and certainly not the last man to die for love in New Mexico.

The next year Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led 300 Spanish soldiers and 800 Indians north to find the cities of gold. At Hawikuh he avenged Esteban, but found no gold—just flat-roofed mud buildings. He was horrified (it would take centuries for Pueblo Revival architecture to catch on). Pushing east he wintered on the Rio Grande, just north of present-day Albuquerque, where conflict soon broke out with the Pueblos. After much slaughter the Spanish headed east, still searching for those golden cities, but finding Kansas instead.

Coronado’s failure so discouraged the Spanish that 40 years passed before they ventured into New Mexico again. Although native resistance blocked settlement efforts in the 1580s, Juan de Oñate led 400 men (130 of whom brought their families with them) in a grand caravan of 83 wagons and 7,000 head of stock up the Rio Grande in 1598. In time he battled the Pueblos, explored the region and established a town at what became Santa Fe in 1609. Work on the Palace of the Governors began in 1610 (Santa Fe is the oldest capital city in the United States). For his troubles Oñate was recalled and tried and convicted of misconduct. New Mexico has always been tough on politicos.

Spanish-Pueblo Alliance

By 1680 there were roughly 2,900 Spanish settlers in New Mexico. The natives outnumbered them 10 to one. Led by San Juan war captain Po’pay, the Pueblo people rose in rebellion in 1680, killing more than 400 Spanish settlers, plus 21 priests, and driving the rest south to El Paso del Norte. Po’pay became the only Indian leader in American history to lead a successful rebellion against the European invader. In time he became a despot and his coalition collapsed, leading to the Spanish reconquest in 1692. In 2005 New Mexico honored him with a statue in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. This did not sit well with many folks, since in the real New Mexico, Hispanics and Pueblo Indians remain to this day about as cozy as Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote.

Don Diego de Vargas reestablished Spanish rule with relatively little bloodshed (70 natives executed and another 400 resistors sold into slavery). The Spanish colony was, in reality, but a thin ribbon of settlement up the Rio Grande, hemmed in on all sides by native enemies—Navajos and Utes to the north and west, Apaches to the south and Comanches to the east. These Indians were relative newcomers compared to the Pueblos, who now were forced into an uneasy alliance with the Spanish for mutual protection.

By 1800 the combined Spanish and Pueblo population along the Rio Grande had reached 35,000. Their livestock was the main commodity, with great flocks of sheep driven south to Chihuahua, alongside wagons loaded with buffalo hides and deer skins. Their horse herds had long been a popular target for Indian raiders. These raiders traded them throughout the plains and mountains, forever altering the ecosystem as well as the native cultures of the American West.

Mexico’s Inconsequential Reign

In 1821 Spanish rule came to a close as the Mexican Revolution ended the colonial period of New Mexico’s history. In that same year William Becknell led a caravan of mules loaded with American trade goods from Missouri to Santa Fe. He returned in 1822, this time with even more goods loaded into wagons, establishing the Santa Fe Trail and a rich commerce between Missouri and New Mexico. Others followed. New Mexicans began looking more to the East than to the South; while cultural ties with Mexico remained strong, political ties were little more than a joke. In the political realm the only true connection between the new Republic of Mexico and the roughly 200-year-old province of New Mexico was the name.

Along the mountain branch of the newly-established Santa Fe Trail, the Bent brothers built an adobe fort. They serviced the trail while also exploiting a rich buffalo hide trade with the Southern Plains tribes. In 1840 they hired Kit Carson as a contract hunter at the fort. With the fur trade playing out, Carson sought other means of employment, soon hiring on as a guide in 1842 with Capt. John C. Fremont to explore the far West. He also soon met and married the Taos beauty Josefa Jaramillo, thus becoming brother-in-law to Charles Bent and well connected within New Mexican society. It was just the beginning of a remarkable career that would mark him as one of the most important citizens of New Mexico and eventually a legendary American hero.

While the rest of the country celebrates Carson, New Mexico tries to officially erase him from its history. His fame as an Indian fighter proves uncomfortable for fantasy New Mexico, where all ethnic groups live in beautiful harmony. Badass Roadrunner naturally loves Carson. They both represent the real New Mexico.

The brief and rather inconsequential period of Mexican rule was brought to an end when Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny entered Santa Fe on August 18, 1846.Mexican Gov. Manuel Armijo and his few soldiers wisely fled south so that the occupation was entirely peaceful. Kearny established a civil government with his Kearny Code and appointed Charles Bent as governor. The new governor was promptly murdered and beheaded in a January 1847 rebellion in Taos. American troops quickly responded, slaughtering the rebels defending the church at Taos and ending the rebellion.

Indian Relocation

By the time the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded New Mexico to the United States, all was quiet. This vast new land already had the population numbers for statehood, but from the perspective of Washington politicos most of those folks were a shade too dark, with a totally unacceptable religion and language. So New Mexico was instead organized as a territory, expanded by the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 and then diminished by the loss of northern lands to Colorado territory in 1861 and western lands to create Arizona Territory in 1863.

The Civil War brought rebel invaders into New Mexico under Henry Sibley and John Baylor. Sibley’s men defeated Union forces at Valverde in February 1862, occupying Santa Fe before Colorado volunteer troops defeated them at Glorieta Pass in March 1862.

As the rebels fled back into Texas, California volunteers under Gen. James Carleton marched into New Mexico. Carleton, looking for a fight, quickly turned his attention to the Indians. The Apaches and Navajos had raided the Rio Grande settlements with impunity for generations, with the Hispanics and Pueblos returning the favor, so that a lively trade in booty and slaves had help fuel the New Mexico economy. Carleton was determined to end all this. His troops, commanded in the field by Col. Kit Carson, defeated the Mescalero Apaches of southern New Mexico’s White Mountains and the Navajos of the Four Corners region in two brilliantly waged campaigns. The natives (some 400 Mescaleros and 8,000 Navajos) were forced onto new reservation land at Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. Guarded by troops at Fort Sumner, the natives suffered terribly.

Carleton’s relocation experiment was finally ended by an embarrassed government, which placed the Navajos and Mescaleros on new reservations in their traditional homelands. The Indian Wars, however, continued until the final surrender of Geronimo in 1886. This was actually good for business since the troops and their many forts and depots provided reliable markets to a cash-starved territorial economy. This reliance on the government, and especially the military-industrial complex of labs, proving grounds and military bases, has continued unabated to this day. Even Roadrunner gets nervous when those folks start setting off explosions.

Ambitious Capitalists

With the end of the Civil War and the subjugation of the Indians, packs of lawyers and ambitious capitalists swarmed over New Mexico. They found natural allies in the corrupt territorial politicians who, even by Gilded Age standards, set incredibly high levels of venality. By controlling the courts and the banks they defrauded many of the Hispanic residents out of their land and water rights. Land Grant litigation remains another sore subject in New Mexico.

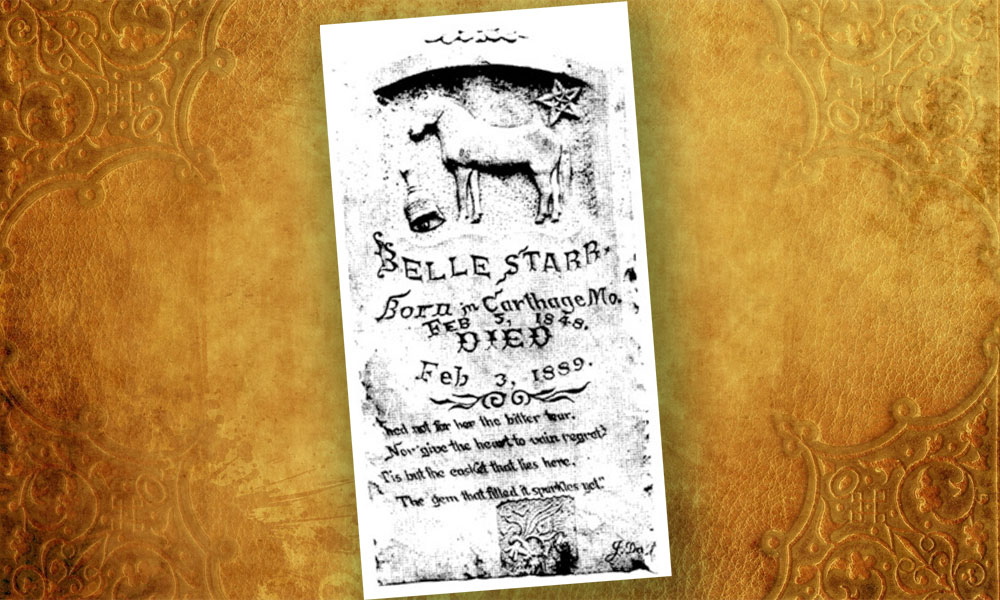

Soon these capitalists controlled vast cattle ranches throughout the territory. They were just as willing to steal from white folks as they were from Hispanics and Indians, and when the courts failed to bring quick enough results, they were willing to resort to violence to achieve their nefarious ends. Now their names grace several New Mexico counties. Billy the Kid waged war on these men, ensuring himself an early grave as well as immortality. The badass Roadrunner loves Billy, for they are kindred spirits.

In time New Mexico’s brand of breathtakingly brazen political corruption was taken to Washington by Albert Fall of Teapot Dome fame. Like the New Mexico reliance on the government trough, this habitual propensity for political corruption has become a mainstay of our state’s identity.

Back East folks continued to be puzzled by what to do with New Mexico. General William T. Sherman, visiting Santa Fe in 1880, gave the local citizens some sage advice in a speech in the plaza: “You used to have nothing but rows in this town, but now it looks like a Sunday school town. You must not expect to spend your time in idleness, you have got to work for yourselves….You must improve your land, and make the most of the resources that your location affords you, and get rid of your burros and goats. I hope ten years hence there won’t be any adobe houses in the territory. I want to see you learn to make them of brick, with slanting roofs. Yankees don’t like flat roofs, nor roofs of dirt.”

General Sherman was no more impressed by the local architecture than Coronado had been. Nevertheless it caught on, even though those flat roofs are about as waterproof as the Titanic’s boiler room. Fortunately it rarely rains.

Path to Statehood

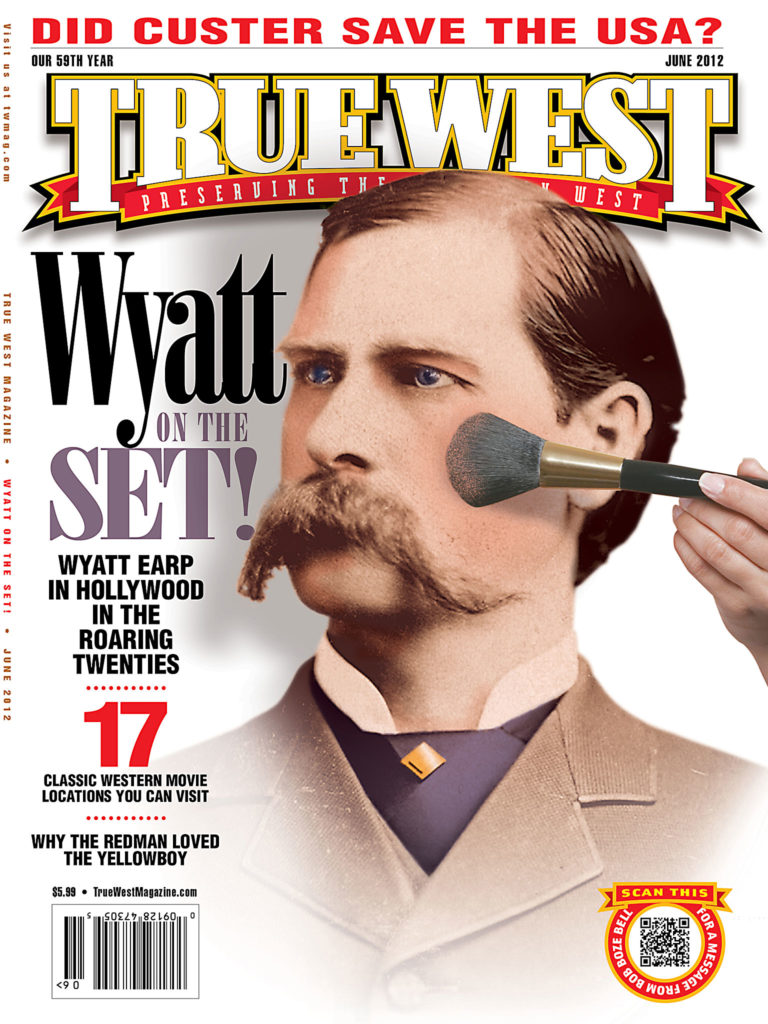

By 1900 New Mexico had a population of nearly 200,000 and powerful friends back in Washington. The territory had provided the largest contingent of volunteers for Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in 1898. The first reunion of that colorful regiment was held in Las Vegas, New Mexico, in 1899 with Teddy in attendance. Many Rough Rider veterans assumed important positions in New Mexico government and law enforcement.

With Teddy soon in the White House, it looked like statehood would proceed smoothly, but efforts foundered over the scheme to combine New Mexico and Arizona as one state. An enabling act was finally passed in 1910, paving the way for New Mexico to become the 47th state in the Union on January 6, 1912.

Roadrunner, as one might expect, did not even notice.

Paul Andrew Hutton is distinguished professor of history at the University of New Mexico. His latest book is Western Heritage from University of Oklahoma Press.

Photo Gallery

That tough Roadrunner chases New Mexico’s history from the beginning of time to statehood.