A few questions puzzle nimrods and veteran shooters alike.

Single Action, Double Action?

One of the many enigmas to newcomers in the Western gun world is the description of operating a “single action” (SA) versus a “double action” (DA). Why are two actions required of the shooter to fire a single-action revolver while only a single act is needed to get the same result from a double-action wheel gun? To fire a SA, the shooter must first pull back the hammer to the firing position, secondly the trigger must be pulled in order to release the hammer and fire the arm. As the hammer is cocked back to the firing position, the SA also rotates the cylinder into battery (lining up a cartridge under the hammer for firing). Thus despite accomplishing two mechanical actions with a single pull of the hammer, the shooter must still pull the trigger in order to complete the firing sequence. The term single action means the operator is only capable of accomplishing one task at a time.

With a DA revolver the simple act of pulling the trigger causes the hammer to be cocked back to the firing position while rotating the cylinder into battery, then releasing the hammer, thus firing the gun. The mechanics of the DA accomplishes two actions through one act of the operator. So, you see, the terms single action or double action refer to the firearm’s mechanical capabilities—or lack of—not the shooter’s.

Muzzleloading Six-Guns?

Why are black powder percussion revolvers called muzzleloaders when they don’t load from the muzzle, like a rifle or shotgun? They’re stoked through the face of the cylinder. Such misleading terminology is like calling an elk a reindeer. They are both of the deer species, but each animal is a different breed with looks and other factors that differ from one another. Just because a cap-and-ball wheel gun uses separately loaded powder and ball ammunition that is rammed home via a loading rod, like a longarm, it’s different because a caplock revolver is charged via the cylinder—not the muzzle. Shouldn’t we call them “cylinder loaders”? Just asking.

Navy Colt—.36 or .38?

The .36 caliber, 1851 Navy Colt (and other cap-and-ball so-called .36 bore revolvers) actually measure .375-inch (a .38 bore size). Yet a modern .38 Special wheel gun’s bore mikes at .357-inch. A rough comparison in power between the .36 round ball and the .38 Special shows that a standard .36 caliber loading of 22 grains of FFFg black powder pushing a 70-grain lead round ball produces around 710 feet per second (fps) of muzzle velocity with approximately 78 foot pounds of muzzle energy. This actually puts the .36 round ball load closer in punch to a .32 S&W Long cartridge which generates about 705 fps of muzzle velocity and a muzzle energy of around 108 foot pounds. The .38 Special, with its 158-grain lead round nose bullet can churn out 800 fps and 225 foot pounds of muzzle energy. Nonetheless in its time, that soft lead .375-inch round ball did some pretty fair damage, especially when the medical technology of the mid-19th century is considered.

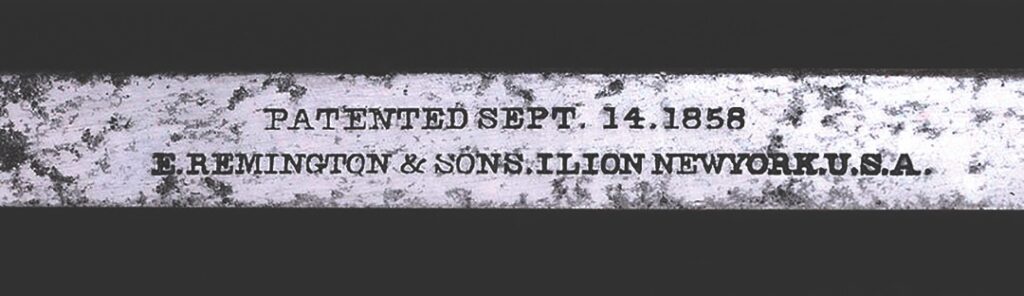

1858 Remington? No such thing!

Many gun buffs refer to Remington’s “New Model Army” and “New Model Navy” percussion revolvers, produced 1863-75 and 1878 respectively, as the “1858 Remington” when no such model name ever existed. This misnomer can be traced back to the early 1960s, when Val Forgett, founder of Navy Arms Company, decided to add replicas of the famed Civil War-era Remington to his growing list of reproduction black powder revolvers. In order to avoid problems with Remington Arms Co., Val told me he decided to name his percussion six-gun after the patent date found stamped along the top of the 1860s original E. Remington & Sons revolvers barrels which read “PATENTED SEPT. 14, 1858.” Shooters, collectors and arms dealers alike never bothered to find out what E. Remington & Sons officially dubbed their revolvers, and just accepted Forgett’s sales title of his Remington repros. Now arms scholars, dealers, firearms auction houses and others know the New Model Army or Navy model by Forgett’s “made-up” sales name. It’s the rare gun fan who calls them by their rightful moniker. No foul no harm, but it’s interesting how a made-up 20th-century handle can be accepted as “official” for a 160-plus-year-old firearm. Think about it; maybe you have your own firearms conundrum.