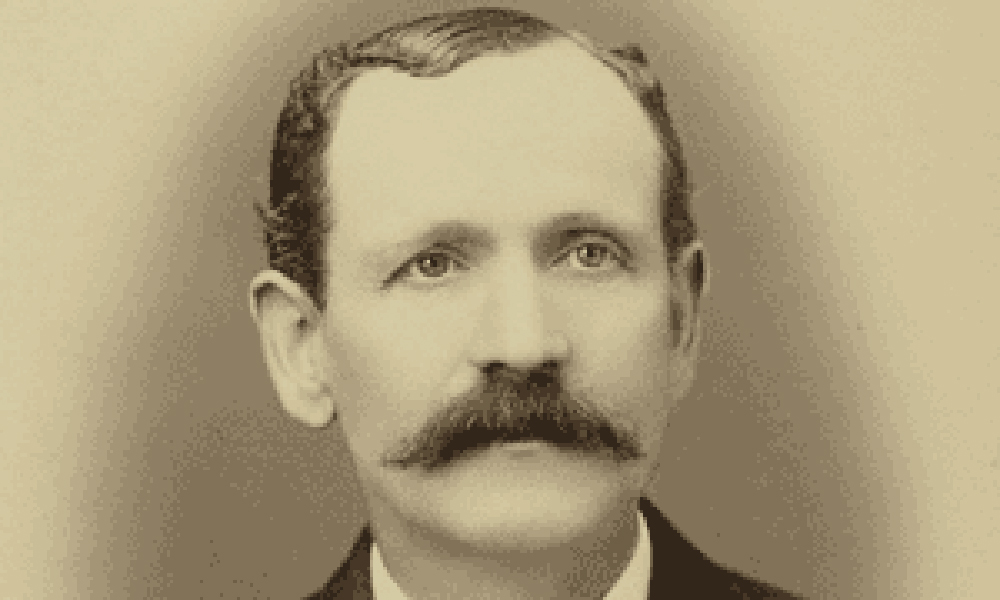

Long before he became acting sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, and later marshal of Abilene, also Kansas, James Butler Hickok had served in several law enforcement capacities. His first appointment was as one of four constables elected early in 1858 by the citizens of Monticello, Johnson County, Kansas, to serve the local magistrates. Then came the Civil War.

Long before he became acting sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, and later marshal of Abilene, also Kansas, James Butler Hickok had served in several law enforcement capacities. His first appointment was as one of four constables elected early in 1858 by the citizens of Monticello, Johnson County, Kansas, to serve the local magistrates. Then came the Civil War.

“William Hickok” as he was known to most of his companions during the War before the more familiar “Wild Bill” earned him notoriety in southwest Missouri and parts of Arkansas, rendered “signal service” to the Union. In fact, General John B. Sanborn, who commanded the District of Southwest Missouri, in later years declared that Hickok was the best and coolest scout he had.

Colonel George Ward Nichols’ article on “Wild Bill” published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in February 1867, contained some fiction, but it did describe some of Hickok’s real activities behind enemy lines, and prompted editorial comment in a number of Kansas and Missouri newspapers, together with statements from those who knew the real Hickok. For the historian, however, unraveling fact from fiction is a task far from finished, yet one thing is certain— Hickok was a resourceful individual who got himself out of a number of hazardous situations during and following the conflict.

Hickok first entered government service as a wagonmaster in the fall of 1861 and served until September 1862. There is then a gap until early 1864 when he is listed as a provost marshal’s police detective. It is this missing period that is of most concern, for it covers the time when, according to Harper’s, he scouted for General Curtis in Arkansas. Perhaps he did (that claim is still under investigation); but recent research, backtracking from 1864 reveals that his employment by the provost marshal at Springfield probably began sometime in 1863. In this capacity, Wild Bill carried out sometimes bizarre tasks. Some of these included visiting saloons to check on the number of soldiers drinking when they should have been on duty; or investigating the activities of known liquor dealers who did not have a license.

On occasion, “William” Hickok (curiously, no one seems to have questioned the fact that he signed himself J.B. Hickok on official documents) was also ordered into parts of Missouri and Arkansas, under secret orders, in pursuit of wanted individuals. One time, Detective Hickok was ordered into a Missouri township near Springfield to obtain $1,000 in cash from a wanted individual and two of his companions. Hickok was also to make an inventory of their property to that amount. Not surprisingly, Hickok reported back that nothing was achieved as all three men had disappeared.

By April 1864, Hickok had had enough of chasing shadows and miscreant soldiery, and on April 2, at his own request, he was transferred to the quartermaster and reengaged as a scout. In June, Sanborn enlisted him. Hickok was paid five dollars a day and was supplied with a horse and equipment, which presumably included firearms. From then on, the “Wild Bill” of Harper’s and the real Hickok blended together to embark upon a period of scouting and spying that has become legendary.

Following the end of the war, and the much publicized shoot-out at Springfield with his erstwhile friend Davis K. Tutt on July 21, 1865, Hickok was at a loose end. Late in January 1866, however, his old quartermaster, Captain Richard Bentley Owen, immortalized in Harper’s as “Captain Honesty,” was transferred from Springfield to become quartermaster in Fort Riley. He sent for Hickok and appointed him government detective to “hunt up public property,” for which he was paid the princely sum of $125 a month (later reduced to $75). In this capacity, Hickok tracked down deserters and others who had “misappropriated” government mules and horses. Hickok proved his worth.

In May 1866, Wild Bill was detached from the post to guide General William T. Sherman and party to Fort Kearny, Nebraska. Oddly, in the 1880s Sherman wrote to Buffalo Bill Cody reflecting upon the trip and his admiration for him. Cody promptly published the letter in his show programs, though he was well aware that Sherman had gotten his “Bills” mixed up, for in May 1866 Cody was still in Leavenworth. At Fort Kearny, General John S. Pope, then engaged Hickok as his guide to Santa Fe. Hickok returned to Fort Riley in September.

General Hancock’s campaign against hostile Indians in Kansas early in 1867, led to Hickok being transferred from detective work to scouting for Lt. Col. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. He served Custer until July 31 when hostilities ceased. Within weeks it was reported that he had been appointed as a deputy United States marshal.

Some have claimed that Hickok was appointed deputy U. S. marshal at Fort Riley as early as 1866, but no documentary proof has been found. Rather, available records unearthed in Washington indicate that Charles C. Whiting, the newly appointed U. S. marshal for the District of Kansas, appointed Hickok to deputy in August 1867.

According to official records (there are some gaps), Hickok served intermittently as a deputy between 1867 and 1870, and earned in excess of $1,000 in fees and expenses. He was now involved in Federal rather than civil cases. These included desertions from the army, horse and mule thefts, illicit liquor sales and counterfeiting U. S. currency. The earliest case found to date involving Hickok was in October 1867 when he arrested one James Quinlin who had been subpoenaed to appear in Topeka in the case of the United States vs. John Reynard, the charge—counterfeiting.

When Hickok arrested a man named John Hurst, Marshal Whiting and Deputy U. S. Marshal B. Searcy were called as witnesses. Late in 1867, both he and Hickok were featured in an amusing comment in the short-lived Ellsworth Tri-Weekly Advertiser. In the first issue dated December 25, the editor remarked that when he came to move his printing press into the new office he needed some assistance, and Hickok and “Captain Searcy” offered to help. “If some of our printer friends had seen Wild Bill take hold of the heavy fly-wheel of our Wells’ Power Press and lift it over the stair step bannister – two and a half feet high – they would exclaim appropriately and westernly, ‘bully for Bill.’”

Counterfeiting was a lucrative pastime, and in 1870, Hickok himself was a victim. In Junction City he roomed with a man named James Atkinson. Atkinson blithely informed Hickok that he had been in the habit of passing dud money, but if it was recognized he took it back. Wild Bill was not impressed. Unfortunately for Atkinson, one such note which he had circulated at a race track in Missouri, was passed to Hickok. Wild Bill was furious. His inquiries led to Atkinson, and he immediately filed a complaint and swore out a warrant. Learning that Atkinson had fled to Abilene, Hickok set off in pursuit. It is likely that he enlisted the aid of Abilene’s marshal, Thomas J. “Bear River” Smith, in locating his quarry. (Smith was murdered in November which, ironically, paved the way for Hickok’s own appointment as marshal of Abilene later in April 1871). However, when counterfeiter Atkinson finally came to trial in October, the case was not fully prosecuted; he escaped imprisonment, and doubtless made himself scarce.

During 1868-70 Hickok was involved in several horse and mule theft cases. In March 1868, when Marshal Whiting learned that the army had some alleged horsethieves in custody at Fort Hays, he wrote to the commanding officer on March 19 and requested that he “notify Mr. J.B. Hickok at Hays City who will promptly respond to your notice.” Nine days later, Hickok himself wrote to the post commander requesting a guard to help him convey his prisoners to Topeka. Accompanying Hickok on this occasion was his longtime friend William F. Cody, not yet generally known as “Buffalo Bill.” Cody was a government detective who had been ordered in pursuit of a gang of thieves—some were thought to be the men in custody at Fort Hays. Hickok, Cody and a military escort delivered the men safely to jail in Topeka ,where they eventually went on trial.

In May 1869, shortly after returning from a visit to his mother’s home in Illinois, Hickok was ordered to Fort Wallace to escort two alleged horse thieves and two witnesses to Topeka. The men, Silas Baker and Willard Curtis, were later sentenced to four-and-a-half years in the state penitentiary.

In Topeka, however, Hickok learned that an incident at Ellsworth in March, threatened his own future as a deputy U. S. marshal. A number of Pawnee Indians were killed by local residents who feared that they would go on the rampage. Three of those alleged to be involved were reported to be Deputy U. S. Marshals John S. Park, Chauncey B. Whitney and B. Searcy (sometimes spelled Circey). The deputies had tried to ease the situation and arrest the Indians for their own protection, but the subsequent shooting led to U.S. Marshal Whiting being called to account for their actions. In defense of his deputies he described Park and Whitney as good men, but for a reason not disclosed, said that Searcy was not in his employ and that he was a “man of bad character. One of the worst, in fact, to be found on the Western border of Kansas.”

The ax fell, and on May 19 Whiting was dismissed. In the months that followed, his health deteriorated and on January 2, 1870, he died, a much maligned and mourned individual. In his place, however, the government appointed Dana W. Houston who made it his first task to interview all Whiting’s deputies and many of those appointed by the district court. Many were fired, but Hickok was among those Houston retained.

Between his duties as the acting sheriff of Ellis County in the fall of 1869, Wild Bill continued to act as a deputy U. S. marshal. In November he obtained a warrant for the arrest of illegal timber cutters reported to be at work on Paradise Creek, some miles from Fossil Creek Station (present day Russell). Arriving by train, Hickok hired a horse and set out. Years later, Adolph Roenigk recalled that when Wild Bill stepped off the train, he “wore a broad brimmed hat and a brand new buckskin suit with fringes on his elbow sleeves and trouser legs. A pair of sixshooters strapped to his sides, he made the appearance of just such a picture as one could see on the cover of a dime novel. . . .” However, with the help of First Lieutenant L. W. Cooke of the Third Infantry, Wild Bill arrested John Hobbs, Charles Hamilton and Charles Vernon, who were all taken to Topeka. The outcome of the trial is not known, or for that matter, if one actually took place, though Hobbs was a well-known character in Hays City in the late 1870s.

Time will doubtless disclose more information on Hickok’s services in law enforcement, but from what we have learned so far, there is little doubt that Wild Bill was indeed a useful and reliable individual in whatever capacity he was called upon to act.