We’ve long held a fascination for the gunmen of the Wild West, and firearms enthusiasts have been especially interested in the hardware used by them.

We’ve long held a fascination for the gunmen of the Wild West, and firearms enthusiasts have been especially interested in the hardware used by them.

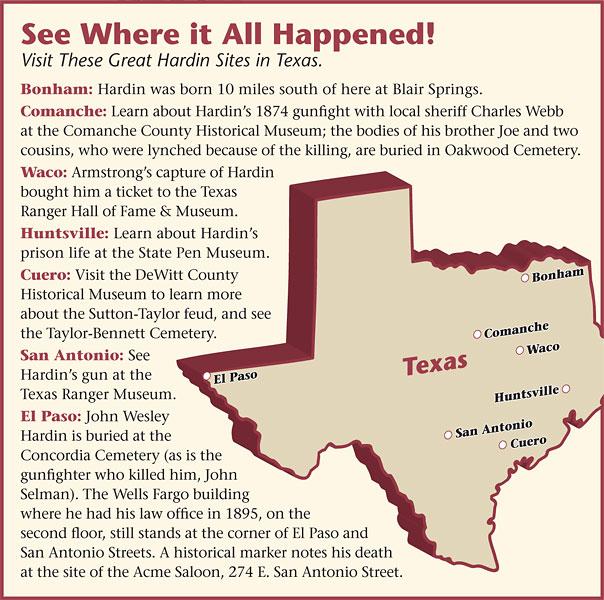

Unlike most Wild West gunmen, who left behind scarce detailed accounts of the guns they had used during their tumultuous careers, John Wesley Hardin is known to have owned or used several solidly documented guns.

Furthermore, thanks to his autobiography, in instances where his hardware is not known, we can guesstimate what arms were most likely used on given dates, based on firearms production records and other known historical facts relating to firearms chronology. (Keep in mind though, Hardin describes some shootings that have not been documented elsewhere and are thus suspect.)

Hardin, arguably the most deadly of the Old West’s gunmen, was a notorious desperado whose career spanned three decades (minus almost 16 years in prison) that ranged from the end of the percussion era of the late 1860s to well into the age of metallic cartridge arms in 1895.

Although firearms were probably nothing more than mere tools to him, there is little doubt that Hardin was a man who appreciated the mechanics as well as every line and curve of his weapons, as his adept handling of his firearms testifies.

“Hardin was an awful quick man”

To say that Hardin was good with his guns would be an understatement. During his lifetime he was considered to be the best shot, the fastest draw, an excellent horseman and the deadliest gunman in the West—and not simply through hearsay. Hard men of arms, who had witnessed and respected his six-gun handling, recorded his abilities.

Late in his lawless career, in 1877, when Hardin was a captive of the Texas Rangers, famed Ranger James B. Gillett was among a group of Rangers who unchained Hardin and watched him in amazement as he demonstrated his skills with a pair of empty Colts. The Ranger remembered he handled the Colts “as a sleight-of-hand performer manipulates a coin.” They also noted his tricks: “The quick draw, the spin, the rolls, pinwheeling, border shift—he did them all with magical precision.”

A Smiley, Texas, man told Hardin’s great grandson he remembered seeing young Hardin “…get on a horse and run that horse at a pretty good speed by a tree, and unload his gun in a knot on the tree.”

Another contemporary recalled that Hardin was so fast that, “When he was young he could get out a six-shooter and use it quicker than a frog could eat a fly.”

In his El Paso years, despite aging and being away from guns for nearly two decades in prison, Hardin was still lightning fast. One eyewitness, who saw Hardin in action in 1895, said, “Hardin was an awful quick man. I was in Mexico one night with him when a policeman started to arrest Hardin for carrying a gun. The policeman made a break for his gun, but he didn’t have time to pull it. Hardin hit the man in the face and then, pulling his gun, told the Greaser to get out of town, at the same time informing him who he was. The Mexican never did come back, and he hasn’t stopped running yet, I bet.”

While in El Paso, Hardin must have felt himself slipping as he passed into his early forties, for in his autobiography he writes of his earlier abilities with guns, “In those days I was a crack shot.…”

In El Paso, he practiced daily in front of a mirror in his boarding room. He wore a special “calfskin vest with built-in holsters containing his two Colt .41 caliber revolvers,” according to contemporary accounts, although neither this vest, nor a bulletproof vest he was supposed to have worn, have ever turned up.

When interviewed for the August 23, 1895, edition of the El Paso Daily Times (just four days after Hardin’s death), his landlady, Mrs. Williams of the Herndon House, stated: “Yes, Mr. Hardin was certainly a quick man with his guns. I have seen him unload his guns, put them in his pocket, walk across the room and then suddenly spring to one side, facing around, and quick as a flash, he would have a gun in each hand, clicking so fast that the clicks sounded like a rattle machine.”

She went on to say, “He would place his guns inside his breeches in front with the muzzles out. Then he would jerk them out by the muzzle, and with a toss as quick as lightning, grasp them by the handle and have them clicking in unison.”

As a final testimony to Hardin’s speed and skill with his guns, El Paso Constable John Selman, a noted gunman himself, would kill Hardin by shooting him in the back!

Hardware for a Young Shootist

Much of Hardin’s early career—from 1868 to 1877—largely involved the use of cap-and-ball revolvers, since the self-contained metallic cartridge arms were relatively new and were not yet nearly as plentiful as they were in later years.

In his life’s story, he frequently makes mention of Colt’s revolvers. Based on the dates of his gunfights, these likely would have been the Model 1860 Army .44s or the 1851 and 1861 Navy models in .36 bore, or possibly cartridge conversions.

Hardin is known to have used at least one 1851 Navy .36, which is identified by serial number in a letter handwritten by Joe Clements, Hardin’s cousin. In the letter, Joe writes that Hardin gave him the gun after Joe had broken up a fight in Gonzales, Texas, and that Hardin got a newer model revolver.

Hardin mentions using a Colt .44 (most likely the 1860 Army model) in his first killing, in 1868, involving a freed slave who had assaulted him. Shortly thereafter, he may well have relied on the same six-gun when a posse of three soldiers discovered his whereabouts and came to arrest the 15 year old for the shooting. The teenaged fugitive selected a spot by a deep creek bed, where they would have to cross, and waylaid the troopers.

In this ambush, which young Wes described as “war to the knife with me,” he killed the three men by “…opening the fight with a double-barreled shotgun and ending it with a cap-and-ball six-shooter.”

Several years later, when Hardin was captured in Pensacola, Florida, on July 23, 1877, he had a ’60 model, .44 cap-and-ball Army Colt revolver on him. He had been unable to draw his six-shooter, since it was strapped to his galluses—much to the relief of the arresting officers.

In recounting his many other fracases, Hardin does not go into detail as to the particular type of weapons used. Like many other Westerners of the day, Hardin referred to them as a cap-and-ball six-shooter or, simply, as “my pistol.” Texas’s Public Enemy No. 1 also spoke of shooting a man with a derringer. Again, he doesn’t stipulate the type or caliber, and such a weapon at that time could have been any of a myriad of hideout pocket pistols.

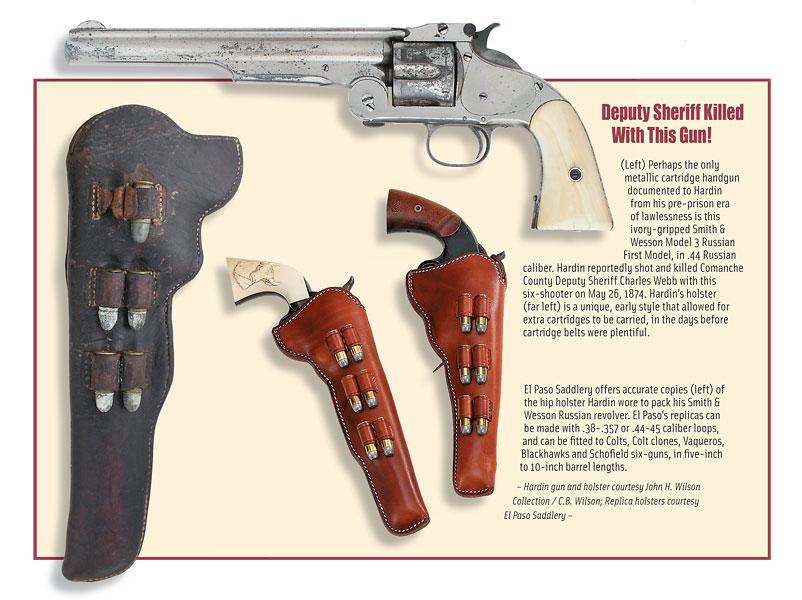

One of Hardin’s known six-guns is a Smith & Wesson Model 3 Russian First Model, in .44 Russian chambering, which he used to kill Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb in Comanche, Texas, on May 26, 1874. This shooting brought about Hardin’s eventual capture and jailing. It is perhaps the only documented metallic cartridge six-gun from Hardin’s pre-prison era of lawlessness.

Although he preferred handguns, he was known to have also used longarms in several shoot-outs. Beside the above-mentioned incident in 1868, when he used a double-barreled shotgun to kill some soldiers, Hardin also used a shotgun to kill Jack Helm in July 1873.

Helm, a former Texas police captain and the DeWitt County sheriff, was also a deadly rival of Hardin’s in the notorious Sutton-Taylor feud. Hardin, who fought for the Taylors, gave Helm a broadside with a British W.&C. Scott & Son, double-barreled, 12-gauge percussion shotgun as Helm approached him. Hardin’s partner, Jim Taylor, then shot the sheriff several times in the head with his six-gun. This Hardin shotgun is on display at the Buckhorn Saloon & Museum in San Antonio, Texas.

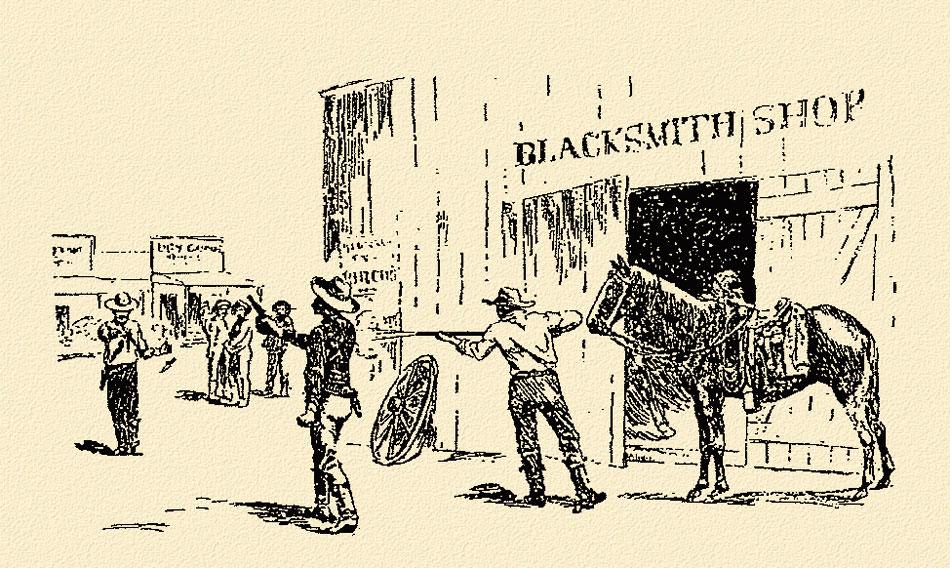

On another occasion, the failure of the cap to ignite the main charge on a double-barreled caplock scattergun saved one lawman from joining Hardin’s long list of victims. During a running horse battle in drizzling rain, Hardin and Jim Taylor were escaping after shooting Deputy Sheriff Webb. When Texas Ranger Capt. John R. Waller caught up to the fugitives, he rode hard at them. The outlaw later recalled “…I wheeled, stopped my horse, and cocked my shotgun. I had a handkerchief over the tubes [nipples] to keep the caps dry, and just as I pulled the trigger the wind blew it back and the hammer fell on the handkerchief. That saved his life. Waller checked up his horse and broke back to his men.”

Rifles also sometimes made up Hardin’s personal arsenal. In his autobiography, he gives an account of firing at some pursuing lawmen with a “needle gun,” a frontier term for the .50-70 Allin conversion of the Springfield rifle—an early trapdoor model.

On another occasion, while trailing cattle to Kansas in 1871, Hardin holed up with his Winchester rifle in the bushes of his campsite and got the drop on a group of men who were after him. Based on the date of this incident, this likely would have been Winchester’s 1866 Model—originally dubbed the “Improved Henry.”

Last Guns of the Last Gunfighter

After Hardin’s release from prison in February 1894, the governor of Texas granted him a full pardon. Passing the bar soon afterwards (while in prison, Hardin had made an attempt at reforming by studying law and theology), the ex-convict began practicing law. Yet his inner demons were still plaguing him, and the hair-trigger-tempered Hardin quickly reverted to his old ways of gambling and drink.

The firearms from this notorious Texas pistoleer’s final years are solidly documented through the official court records resulting from an arrest and his murder. They present an interesting assortment of handguns.

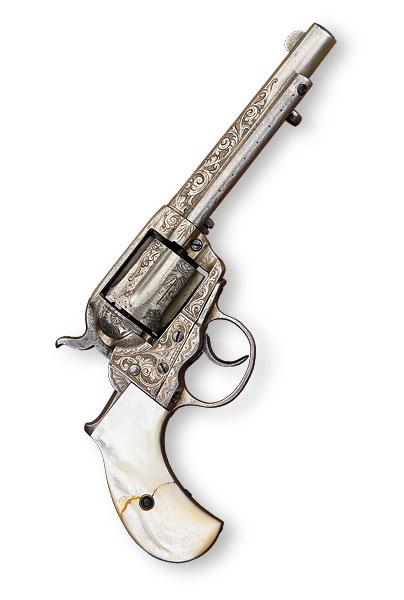

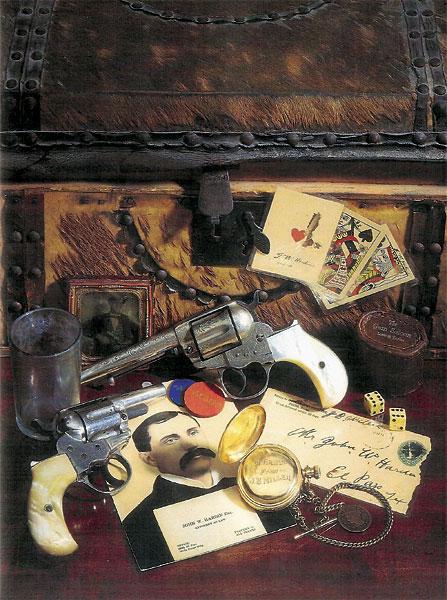

Among these was a nickeled 2½-inch, ejectorless, .38 caliber Model 1877 Colt Double Action “Lightning” with two-piece pearl stocks. This six-shooter was presented to him (along with an engraved and gold-filled Elgin pocket watch, a watch chain and coin watch fob) from his cousin by marriage, “Killer” Jim Miller, for representing him in a legal dispute. Hardin also owned two .41 Long Colt-chambered 1877 Colt Double Action “Thunderers.” One was a 4½-inch barreled, ivory stocked and nickel plated pocket revolver (with ejector) and the other had a barrel of five inches and was nickel plated and ornately engraved with two-piece pearl grips.

Hardin also owned an ivory-stocked, 4¾-inch barreled, 1873 Colt Single Action Army in .45 Colt chambering, in nickel finish, with the ejector housing removed (quite possibly by Hardin himself, for an easier and faster draw from his pocket). Hardin’s 1873 Peacemaker, as well as one of his .41 Long Colt 1877 Colts (the ivory-stocked 4½-inch model), are on display at the Autry National Center’s Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California.

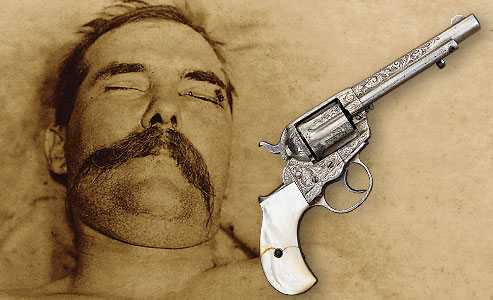

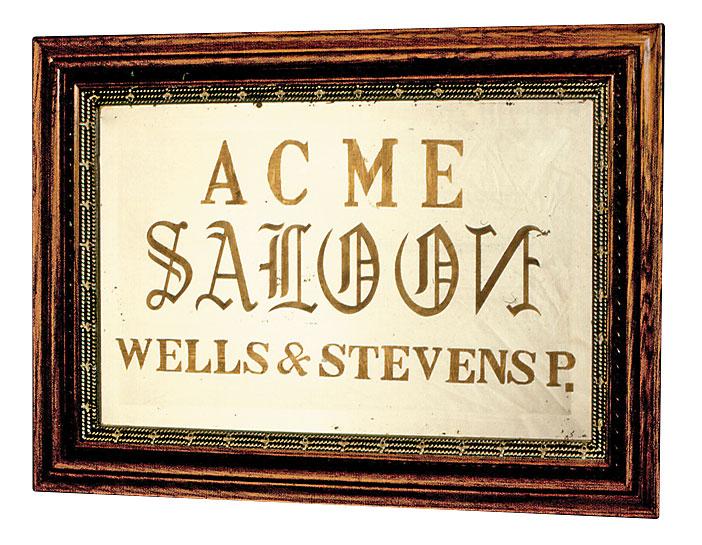

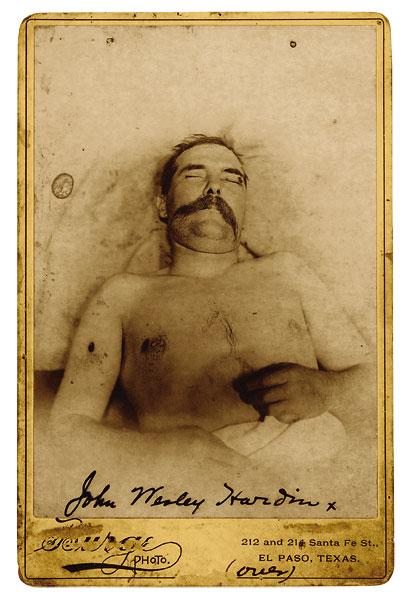

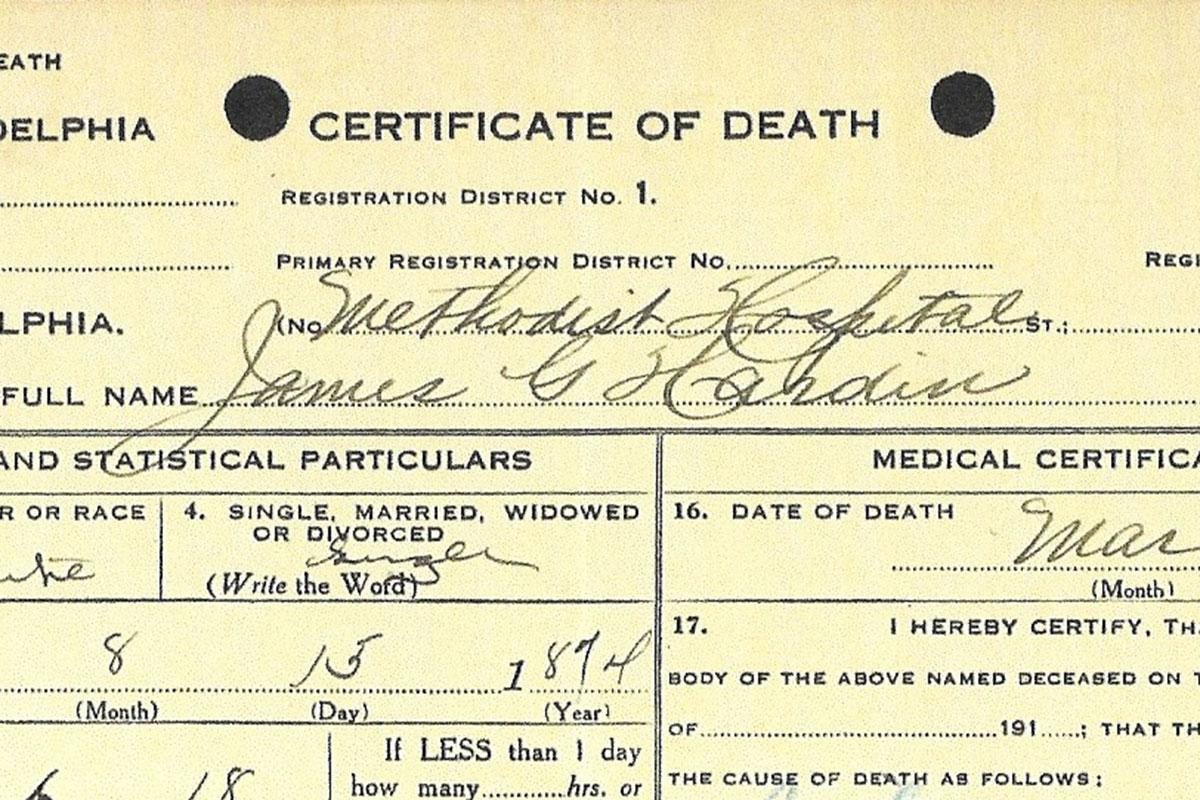

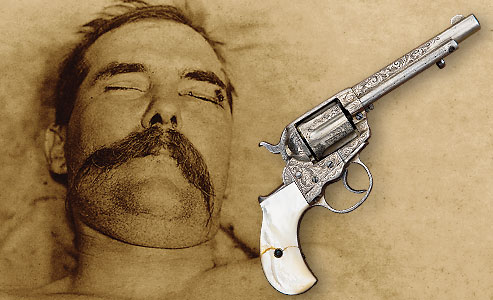

At the time of his death, 42-year-old Hardin was packing a Smith & Wesson Double Action “Frontier” in .44-40 chambering, with black factory hard rubber grips. On the afternoon of August 19, 1895, Hardin threatened the lives of Constable John Selman and his son. That night, Selman walked into the Acme Saloon in El Paso, where the noted gunman was drinking and rolling dice, and coolly shot Hardin in the back of the head with a Colt .45 Peacemaker, killing him instantly.

Ironically, Selman claimed that Hardin had seen him come in to the Acme and went for his guns, although few believed this story. As a matter of interest, Episcopal Minister E.H. Higgins, who had been called to the Acme to attend to Hardin after the shooting, suggested that if Selman had shot Hardin through the eye from the front, “it would be remarkably good marksmanship,” and if Selman had shot him from behind, “it was probably remarkably good judgment.”

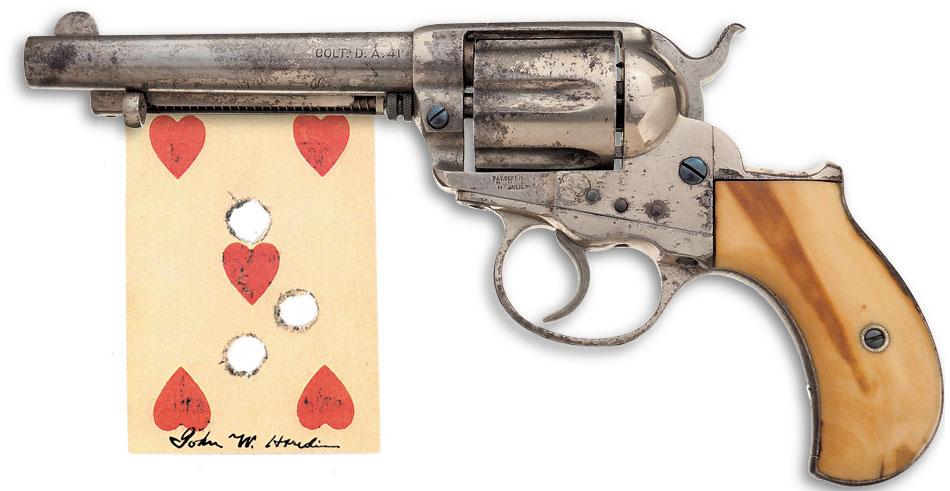

Had Selman indeed faced Hardin in a fair fight, the outcome might well have been different. J.W. Hardin was a bona fide expert with his six-guns. In his last year of life, he put on a number of shooting exhibitions during which he shot holes in faro cards, then signed them and gave them away as souvenirs. Most historians, including this writer who has carefully measured the bullet holes in some of these cards, feel that Hardin used his .41 caliber Double Action 1877 Colts to perform these shooting feats. A handful of these unique gunfighter mementos still exist and bring a premium price with collectors, as do any of Hardin’s firearms.

Like so many other shootists of the Old West, Hardin had many guns during his long and violent career. Thanks to court records, Hardin relatives and dedicated historians and collectors, like El Paso’s late Robert E. McNellis, who uncovered several of Hardin’s documented guns and other personal memorabilia, several examples of the Texas gunman’s weaponry have survived. These valuable artifacts not only reveal the types of arms used by Old West gunfighters, but also provide the rare opportunity to see the actual tools of this deadly gunman—one of the frontier’s most notorious shootists—in his violent profession.

Phil Spangenberger writes for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

–Courtesy Buckhorn Saloon & Museum in San Antonio, Texas –

–Courtesy Ryan McNellis, El Paso Saddlery Collection –

This five-inch barreled, nickeled and engraved, pearl-handled .41 Colt “Thunderer” was taken from Hardin in May 1895 by Deputy Sheriff Will Ten Eyck for “unlawfully carrying a pistol” in the Gem Saloon in El Paso, Texas. It was never returned to him, and Ten Eyck later repaired the cracked grip.

– Courtesy Kurt House Collection / By Paul Goodwin –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –

– Replication of playing card

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Bonhams & Butterfield –