San Francisco, 1853: As traveler John Steele strolled along a bustling thoroughfare, he suddenly found himself being crowded against a doorway and shoved into a small room by a stranger.

San Francisco, 1853: As traveler John Steele strolled along a bustling thoroughfare, he suddenly found himself being crowded against a doorway and shoved into a small room by a stranger.

Reacting instinctively, Steele thrust his right hand against the door to prevent his assailant from shutting him inside, and with his left hand, he withdrew and cocked one of a pair of palm-sized, single-shot derringers he was carrying secreted inside his coat. Spying another bruiser standing in a side door, Steele quickly raised his pistol, causing the would-be attacker to withdraw, shutting the door behind him.

The fast-thinking Steele swiftly drew his second pistol. His initial would-be robber disappeared through another door on the opposite side of the room, and Steele made his way back onto the street.

Steele later recalled, “…on regaining presence of mind, [I] saw that the room was only about six feet square, but containing three doors.…The fact that I had been pursued by a robber became apparent, and only instant resort to the pistols saved me from being robbed or worse. The room, into which I was so suddenly pushed, was evidently a prepared trap….”

The Civil Way

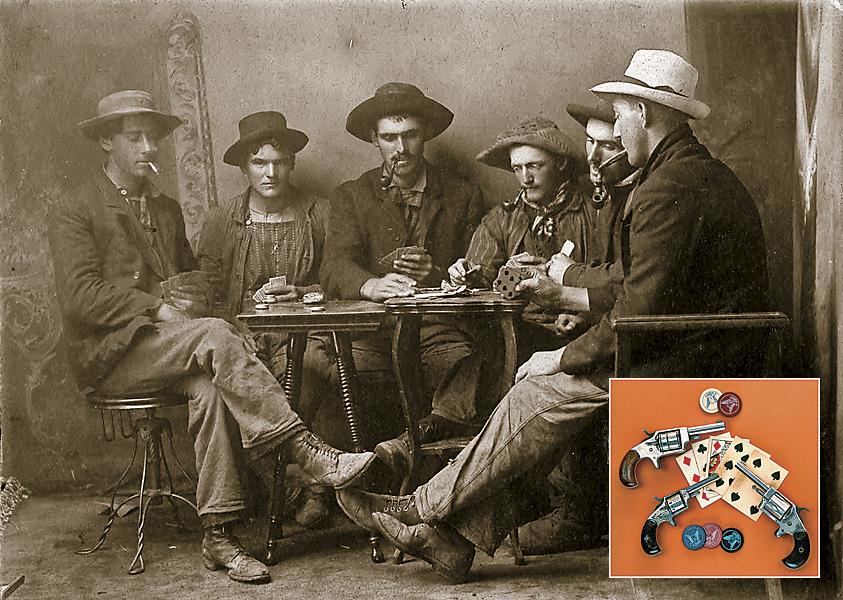

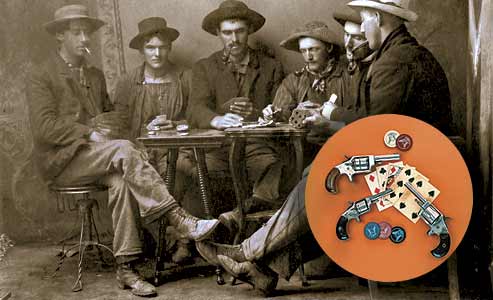

In the early days of the frontier, few laws restricted the carrying of firearms. In this wild, unsettled region—whether in the wilderness or in town—packing a weapon for personal defense was often a necessity. Many frontiersmen wore their guns openly.

As soon as civilization found its way onto the frontier, a number of Western communities began prohibiting the carrying of guns in public. Regardless of such local statutes, peace officers, gamblers and those who lived on the fuzzy edge of law and order—along with some respectable bankers and shopkeepers—found it advisable to pack iron when out and about. In their effort to maintain decorum, the practice of carrying their hardware concealed

from public view became de rigueur.

Although a handful of states once restricted concealed carry, all of them now allow it; Illinois became the last state to pass a law permitting concealed carry, with license applications first available on January 5, 2014. For those who wish to conceal their firearm, in accordance with the laws, of course, take a note from how frontier gentlemen and ladies hid their weapons out West.

Pocket Protectors

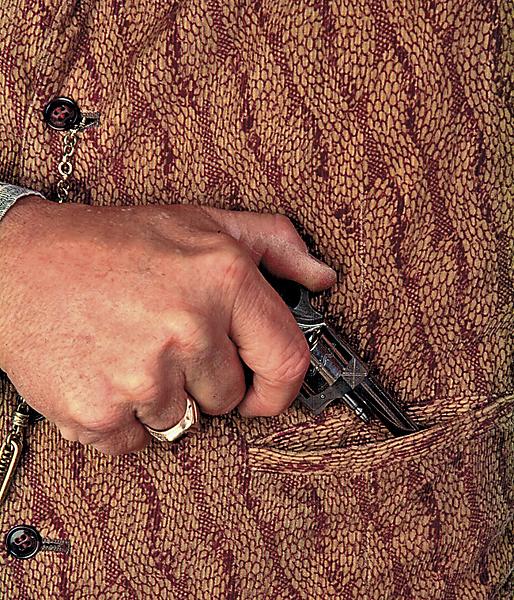

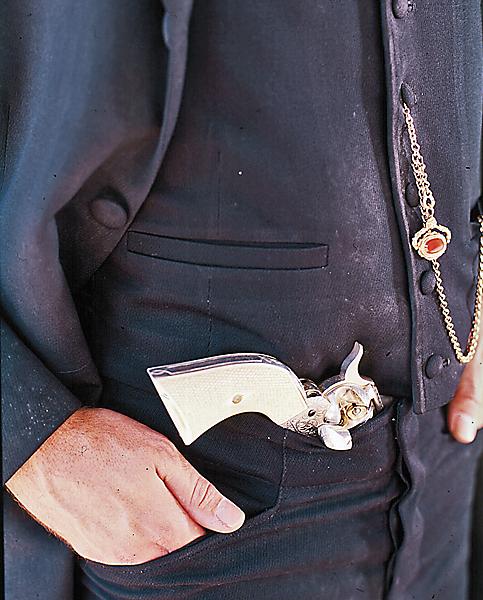

The most commonly employed method of “going heeled” in the Old West was carrying a handgun in one’s pocket—or tucking it in the waistband, perhaps covered by a vest or coat. To hide long-barreled six-guns, frontiersmen would often lop the barrels short to conceal the weapon. Bear in mind that the 19th century was a time when trouser belts were seldom worn and pants were held up by either the use of galluses (suspenders) or a natural fit.

Besides openly packing his big, eight-inch barreled Smith & Wesson American .44 revolver, El Paso City Marshal Dallas Stoudenmire kept a Model 1860 Colt .44 cartridge conversion, with its barrel shortened to around 2½ inches, as his hideout gun.

Porter Rockwell, known as Mormon leader Brigham Young’s “Avenging Angel,” was known to carry a similar cap-and-ball Colt .44 as his concealed dealer

of vengeance.

Former Texas Ranger-turned-Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Outlaw modified his Colt Single Action with a shortened barrel and had the trigger removed. The rear portion of the trigger guard was left intact to allow for a firm grip, since the gun could only be fired by thumb cocking or by “fanning” it. Unfortunately for Outlaw, this proved to be his undoing in a gunfight with El Paso Constable John Selman on April 5, 1894, when, in a drunken stupor and after killing a Texas Ranger, Outlaw rapidly fired this six-gun several times at Selman, but only succeeded in wounding the lawman in the leg. Selman got off an accurate shot that proved fatal to the gunman.

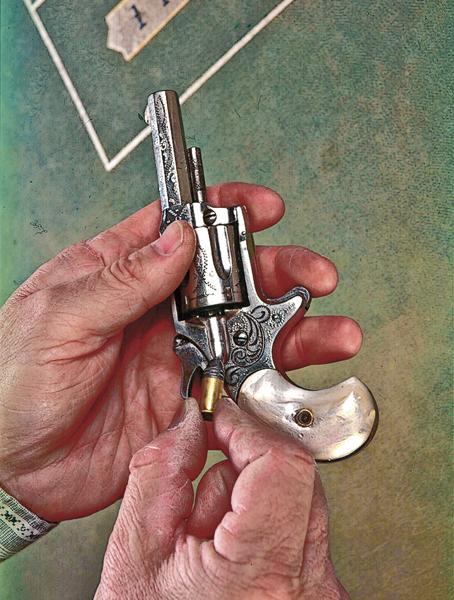

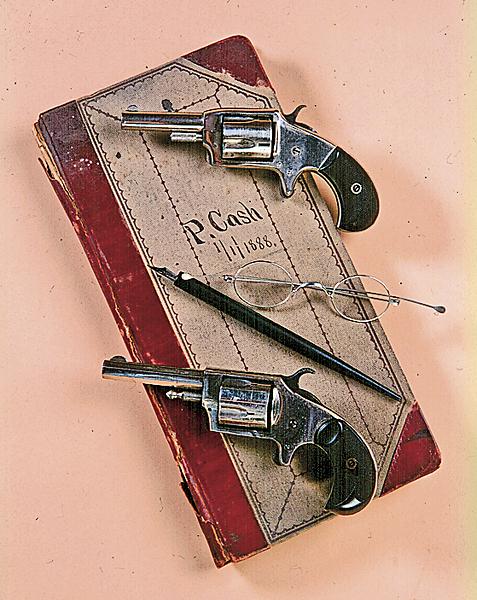

Pioneers looking for a small pistol to slip into one’s pocket could purchase any number of derringers, such as the various Sharps four-barrel pepperbox pistols, Reid’s “My Friend” Knuckle-Duster revolvers or any of several Colt pocket models. Another option included small spur trigger revolvers.

Without a doubt, the most successful of these pocket-type handguns was Remington’s double derringer (also known as the Model 95), of which an estimated 150,000 were produced between 1866 and 1935. When tucked into a vest or coat pocket, a derringer would not produce any more of a bulge in one’s clothing than would a pocket watch.

Some professional gamblers were known to have rigged special devices that allowed them to wear a derringer up their coat sleeve, inside of a hat or in a small holster attached to their galluses. The gun did sometimes get entangled in clothing, however, when the gambler withdrew it from a coat or trouser pocket.

None of these options were advisable to those carrying the big-bore six-shooters that were the preferred armament of many Westerners, as notorious Texas gunman John Wesley Hardin discovered. When he was captured in Pensacola, Florida, on July 23, 1877, Hardin had an 1860 model Army Colt .44 cap-and-ball revolver secreted on him. But since the gunfighter had his six-shooter strapped to his galluses, he was unable to grab it in time, making for a lucky day for the arresting officers.

How to Hide a Big Gun

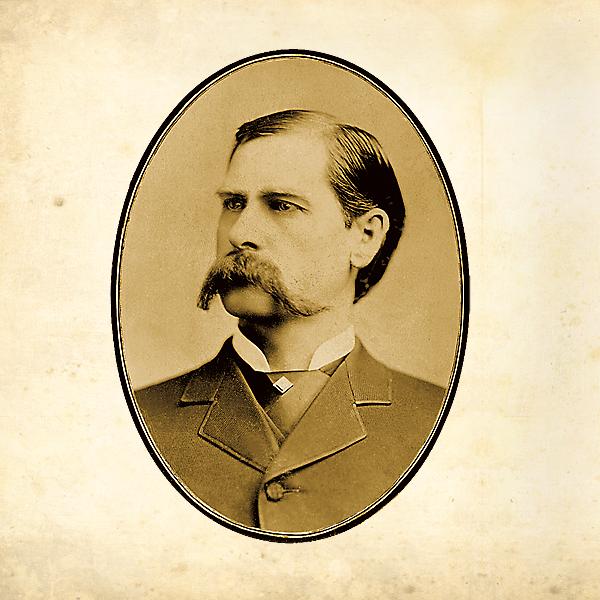

So how did Westerners hide their big six-guns? Wyatt Earp reportedly had a special heavy canvas pocket sewn to the inside of his frock coat, spacious enough to carry a Colt Single Action Army revolver without detection.

Another means of secretly carrying weaponry were the high-topped boots worn by so many men on the frontier. Besides knives, small- to medium-sized handguns—especially the widely sold single-shot boot pistols of the early- to mid-19th century—could easily be hidden in these tall, stovepipe affairs.

Perhaps the most unusual mode of packing a six-gun was that practiced by Hardin in his later years in El Paso, Texas. Eyewitness accounts state that Hardin occasionally carried a pair of .41 caliber, double-action 1877 Colt “Thunderers” in his trouser pockets—with the muzzles pointing up! In an interview appearing in the August 23, 1895, edition of the El Paso Daily Times (just four days after Hardin’s death), Hardin’s landlady said, “Yes, Mr. Hardin was certainly a quick man with his guns…He would place his [unloaded] guns inside his breeches in front with the muzzles out. Then he would jerk them out by the muzzle, and with a toss as quick as lightning, grasp them by the handle and have them clicking in unison.”

A unique mode of packing the Peacemaker Colt—sans holster—was to thrust it into one’s waistband, and then open the loading gate. The opened gate prevented the Colt from sliding down into the pants, keeping it at waist level for a fast draw. Generally speaking, the system worked well, despite one frontier sheriff’s misadventure while relying on this method. He later stated that in one gunfight, he drew his Colt in such haste that he forgot to close the loading gate. He got his first shot off without a hitch, but as the revolver was cocked for a follow-up shot, a cartridge slipped out of its chamber into the loading gate area and jammed the gun. Fortunately for the lawman, his first shot settled the dispute and further gunplay was unnecessary.

Hideout Holsters

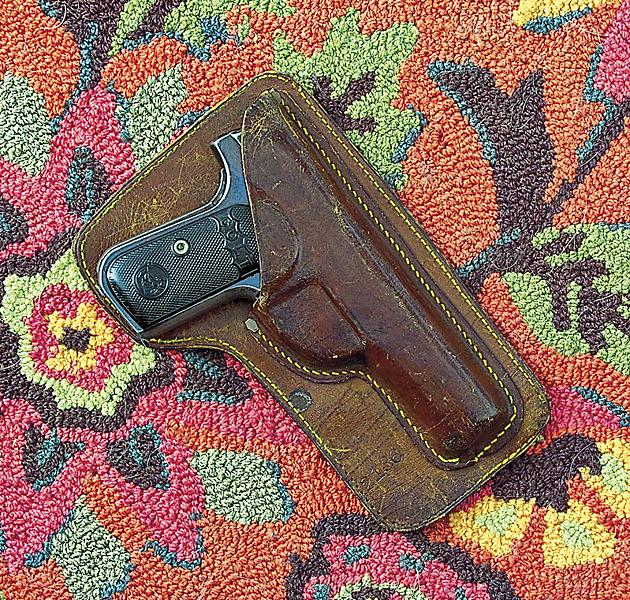

For those who did carry smaller-framed revolvers or the slab-sided semi-auto pocket pistols (invented at the turn-of-the-19th-century), a form of gunleather known as the “hip pocket” holsters often filled the bill. These holsters ranged from simple, folded and sewn leather sheaths—perhaps with a button or spring metal clip for attaching to the waistband or pocket wall—to more complex designs incorporating spring-loaded trigger guard retainers for added security.

A much emulated style involved the use of a flat, rectangular piece of leather (sometimes utilizing two layers stitched together to form a stiff backing) that conformed to the general shape and size of a pocket. To this backing, a sheath that followed the general contours of a revolver would then be sewn. This kind of holster allowed the gun to be positioned for quick and easy retrieval. One example, patented by inventor R.G.M. Phillips in July 1900, not only included the spring-loaded safety shroud over the trigger guard, but it also sported a metal tubular magazine for

extra ammunition.

Regardless of how simply, or complicated, these hip pocket holsters were constructed, the type was never a huge success in the Far West, although the holsters did see limited use. Their lack of popularity was undoubtedly due to the fact that this style of holster was just too small to accommodate the big smokewagons favored by many Westerners.

Heads and Shoulders Above the Rest

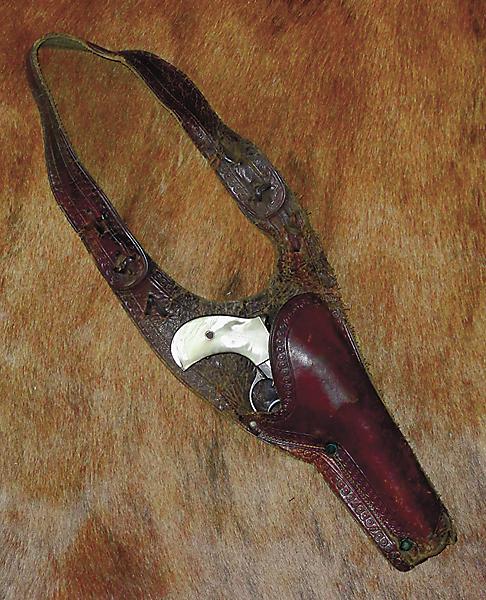

One holster type that did see fair usage out West was the shoulder holster. Contrary to popular belief, shoulder rigs were not a product of the gangster era of the Roaring 1920s. Rather, its roots lie with the gunfighters of the Old West—from both sides of the law. Even shoulder slings were common as early as Colt’s Model 1848 Dragoons. The shoulder holster allowed Western shootists the luxury of being “well-heeled” while not attracting unwanted attention.

The most common type of shoulder rig used on the frontier, which is believed to be the earliest style, was the “Texas” pattern, which made its debut sometime during the late 1870s. Texas gunman Ben Thompson packed his pistol in such a manner.

This style of shoulder holster was a contoured and pliable, half-pouch-type, single-ply leather scabbard that was sewn, and sometimes also riveted, to a heavier, two-ply back panel. The rig relied on a looped shoulder strap and often a narrower strap affixed to the lower portion of both sides of the harness to secure it in place.

Unlike today’s rigs, this shoulder holster did not have a securing strap connected to the toe of the holster to fasten to one’s belt. That’s because belt loops on trousers were not commonly found on trouser waistbands during the frontier era. This drawback made drawing a slower, two-handed proposition. If trouble appeared to be forthcoming, a savvy gunman might carry his revolver partially withdrawn.

By the late 1890s, a much-improved “Clip Spring” or “Skeleton” model was available. This shoulder holster type may be the collaboration of two Montana saddlers—Al Furstnow of Miles City and E.D. Zimmerman of nearby Custer County-—who began producing the model at about the same time.

This holster style consisted of the stiff, two-ply contoured backing with a single, leather covered, steel spring band, or strap, which supported the frame of the weapon, while the muzzle was held in place by a small socket at the base of the backing. This skeletonized rig left the firearm exposed for fast removal by simply pulling it forward, yet kept the gun held firmly in place. A leather flap covering the upper portion of the handgun sometimes added protection against perspiration and also from snagging on clothing.

The early years of the 20th century brought Westerners the “Half Breed” shoulder rig. Similar to the Texas pouch shoulder rig, the Half Breed differed in that the seam facing the front of the wearer was left open, and the rig used the clip spring to hold the gun in place, giving the shootist the ability to quick draw by pulling the gun forward. The shoulder holster’s full, two-ply leather housing granted the wearer almost complete protection from the gun catching on clothing.

The Half Breed came too late for the Old West era, since Reno, Nevada, holster maker F.R. Lewis did not patent it until 1911, but it did see service during Prohibition when the West was still open and wild. Many of today’s shoulder holsters are based on the Half Breed design.

A Lady’s Companion

Men weren’t the only ones to pack iron in the Old West. Some women, especially the soiled doves of the Western frontier, found it necessary to go armed, though not always concealed.

In writing about the ladies of the evening in Julesburg, Colorado, in 1867, Henry M. Stanley recalled, “These women are expensive articles, and come in for a large share of the money wasted. In broad daylight they may be seen gliding through the sandy streets in Black Crook dresses, carrying fancy derringers slung to their waists, with which tools they are dangerously expert.”

For those women who wished to keep their armament secret, their heavy, bulky clothing afforded a multitude of hiding places. A madam could easily rig a small holster to her stocking garter or attach a tiny derringer to a string so she could tuck the weapon safely out of sight in her apparel. For that matter, almost any size handgun could be fairly well concealed within the folds of a Victorian-era female’s voluminous skirt or bustle.

In colder climes, women often wore muffs—soft cylindrical fur wrappings into which a woman placed her hands from either end to keep them warm. Some firearm companies advertised “muff pistols,” small pistols that could easily be kept out of sight and at the ready, concealed inside these muffs.

Sometimes manufacturers marketed their small firearms directly to the ladies. The small .22 bore, five-shot pepperbox that was the invention of Charles Converse and Samuel Hopkins in August 1866 was manufactured in a small quantity (about 800 pistols) by the Continental Arms Company and sold under the trade name of “Ladies Companion.” Although not overly favored, a few of these did reach the Western market.

Never Fully Dressed Without a…Gun!

Regardless of how a Westerner might have concealed his or her pistol, many folks considered themselves undressed without a weapon. Or, as a frontiersman would put it, they were “not properly heeled” if they weren’t packing iron.

Law and order tried to civilize the Old West frontier in many ways, including with laws restricting the carrying of firearms in towns. But many Westerners found ways to flout such laws. Most didn’t see those weapons…until too late.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

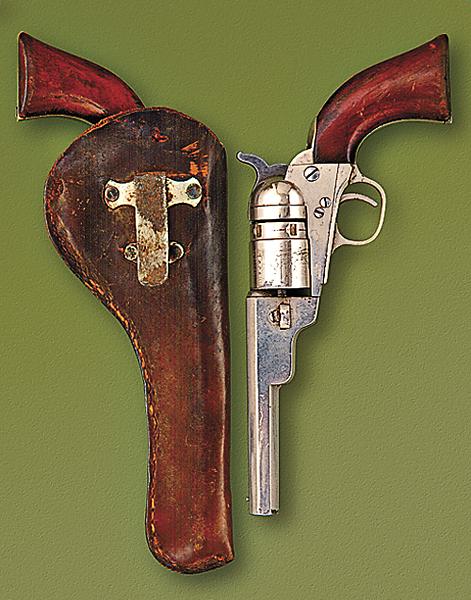

Some frontier-era gunleather producers turned out hideout holsters like this specimen—shown here with a .38 rimfire, five-shot Colt Pocket Conversion revolver—that was designed to be worn clipped to one’s trousers, galluses or any article of clothing desired for concealed carry.

– Stoudenmire photo Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

In the early 20th-century West, when semi-automatic pistols were gaining favor, their slab sides made them ideal for concealed carry, as evidenced by this “inside the trousers” holster with its .32 ACP 1903 Hammerless Colt Pocket Auto. The holster’s backing is inked in old script with “M.S. Hines, Cedar Rapids, Iowa.”

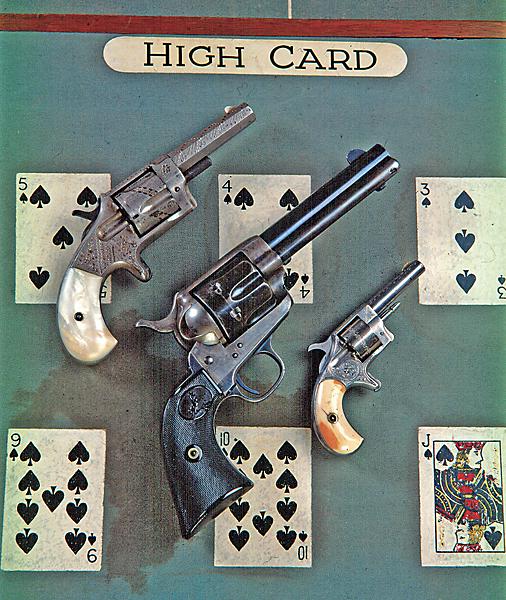

Some gamblers had special hideout holsters made for specific weapons, like this rare and neatly crafted holster fitted to the Sharps four-barrel .22 pepperbox derringer. This unique piece of Old West gunleather has a slanted loop on the reverse side, just large enough to fit over a suspender strap—a handy accessory for a gambling gent.

Early shoulder holsters were simple, like this circa 1900-1910 “Texas” pattern rig. Such holsters hung from the shoulder and were held in place by the wearer’s coat. In this rig fitted to a five-inch barreled 1877 Colt “Thunderer,” the leather features a shoulder strap secured by thongs that can be adjusted for fit.

– Courtesy Guns & Ammo Magazine –

– Courtesy Wells Fargo Bank Collection –

– Courtesy Craig Fouts –