Frank Stilwell got himself shot full of holes, literally perforated from head to toe, outside the railroad depot in downtown Tucson, Arizona, in 1882.

Frank Stilwell got himself shot full of holes, literally perforated from head to toe, outside the railroad depot in downtown Tucson, Arizona, in 1882.

Now, rationality should tell us that this Western gun opera, one of many from those wild days, no longer deserves remembrance, and certainly shouldn’t play a part, no matter how small, in Tucson’s Rio Nuevo Project to reinvigorate downtown.

But it does. Project managers, who’ve just completed a $7 million renovation of the old railroad depot, plan to recognize Stilwell’s murder at a nearby transportation museum, slated to open in January 2005.

Seems strange, no? A hygiene-impaired rodent barks off the wrong guy and gets shipped to the warmer precincts of hell.

Why all the fuss?

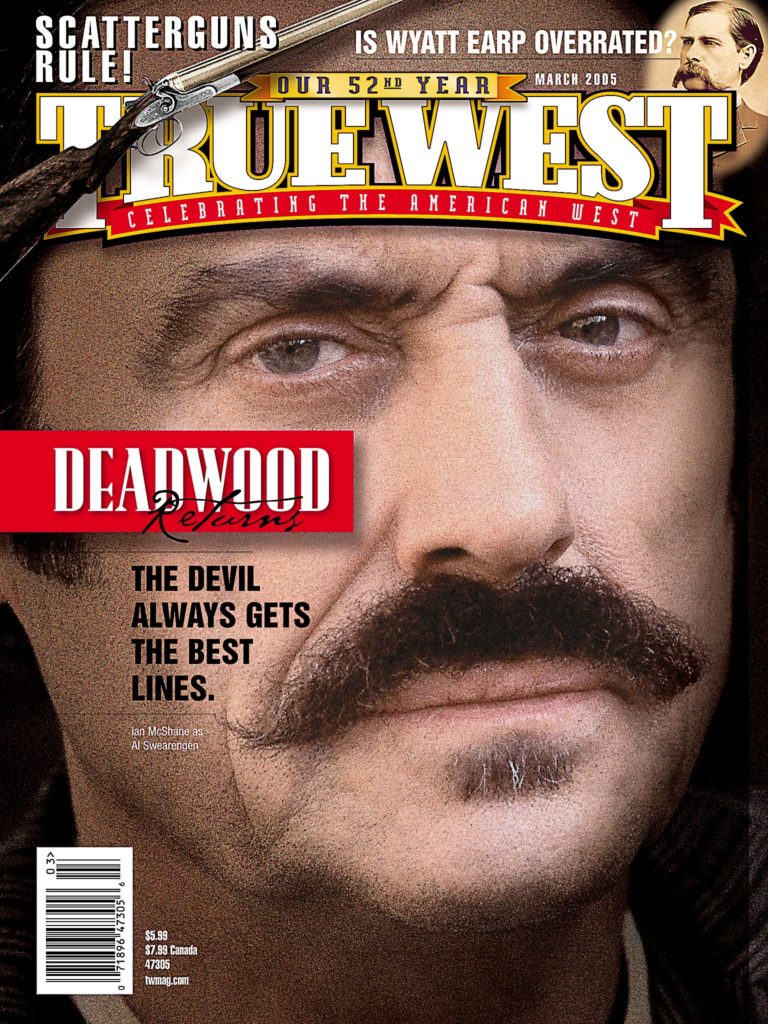

The shooting was a huge deal when it happened, too, because the perpetrator—likely warrantless, even though he claimed otherwise—was a frontier drifter, prospector, gambler and cowtown marshal named Wyatt Earp.

Yes, the Wyatt Earp, who, for reasons too weird for the normal mind to grasp, has become an American icon, a towering figure of the West and a continuing moneymaker through books, movies and tourist destinations from Dodge City to Tombstone.

Which explains the quite rational interest of Tucson’s city planners.

“We’ve been excited about Wyatt Earp since we began working on this,” says Kim McKay, depot project manager. “Everyone who saw the movie Tombstone remembers the scene where Earp shot Stilwell, but I don’t think people realize it happened right here in Tucson. We think it can be a real tourist attraction.”

Armed to the Teeth

The first acts of the Stilwell drama played out in Tombstone in the bitter feud between the lawmen-Earps and the cowboy-rustlers. Everybody knows the story.

After the Earps and Doc Holliday killed three cowboys near the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881, the gang avenged their dead by wounding Virgil Earp and killing his brother Morgan. In both cases, the likely triggerman was Frank Stilwell, a livery stable operator, part-time sheriff’s deputy and part-time stage robber.

Now it was Wyatt’s turn to seek revenge, and to honor his promise to Morgan. As the latter lay dying the night of March 18, 1882, he whispered to Wyatt his last wish, which wasn’t to go to heaven or leave a handsome corpse—it was for Wyatt to kill the man who plugged him.

“That’s all I ask,” Morgan told his brother.

Committed to dispatching Stilwell, and certain that assassins were hunting his entire family, Wyatt convinced Virgil, still suffering from ambush wounds, to return home to California.

While escorting Virgil to the depot in Tucson, Wyatt and his federal posse got a tip that cowboy assassins were awaiting them there.

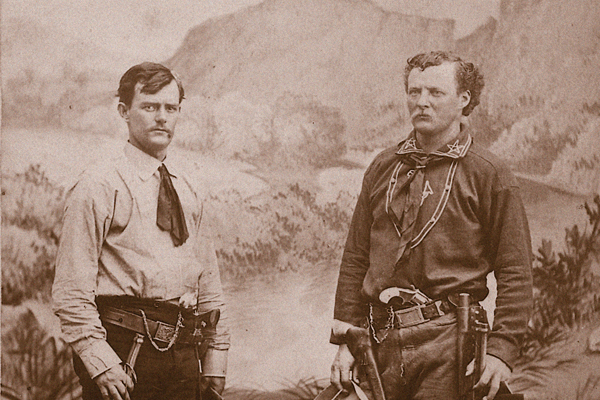

They arrived in Tucson the night of March 20, Wyatt’s party consisting of his youngest brother Warren, Doc Holliday and loyal gun hands Texas Jack Vermillion and Turkey Creek Jack Johnson.

“Almost the first men we met on the platform there were Stilwell and his friends, armed to the teeth,” Virgil told The San Francisco Examiner two months later. “They fell back into the crowd as soon as they saw I had an escort, and the boys took me to the hotel to supper.”

Later, Wyatt spotted Stilwell and Ike Clanton, armed with shotguns, lying on a flat gravel car and peeking into the window of the train in which Virgil sat with his wife Allie. Armed with his own shotgun, Wyatt approached Stilwell and Clanton, the two men making good use of common sense and running like swans.

For Clanton’s part, bolting showed that his IQ was at least slightly larger than his hat size. Speaking of hats, Clanton had left his at the Virgil Earp ambush site, and in the Old West they called that a clue.

Anyway, Clanton made his getaway from the railroad yard. But Stilwell fell on the tracks, with Wyatt right behind him.

Listen to the anger in Wyatt’s own account, from the Denver Republican:

“I ran straight for Stilwell. It was he who killed my brother. What a coward he was! he couldn’t shoot when I came near him. He stood there helpless and trembling for his life. As I rushed upon him he put out his hands and clutched at my shotgun. I let go both barrels, and he tumbled down dead and mangled at my feet.”

Wyatt wasn’t alone. Other members of the posse joined the fun, as evidenced by the coroner’s report. For Earp nuts, it makes cozy bedtime reading, with all its heartwarming talk about buckshot entering the left breast, bullets passing through the left arm, more buckshot shattering the left leg and on and on.

It concluded: “Death was evidently instantaneous although the expression of pain or fear on the face would seem to indicate that the man was aware of his danger, which he sought to avert with his left hand, as it was burnt and blackened with powder, that being the same charge which entered the breast, as was evident from the close proximity of the gun when it was fired.”

Stilwell’s body—“The worst shot-up man I ever saw,” said one observer—was discovered next morning just west of the original depot, where the locomotive ramada stands today.

Not only had Wyatt gotten vengeance, but he saved Virgil’s life. In his Examiner interview, Virgil said: “One thing is certain, if I had been without an escort they would have killed me.”

Wyatt’s Savage Vendetta

The public reacted with horror to the killing. Tucson’s paper raged that the Earp party’s actions were both “outrageous to our citizens” and “damned in the sight of heaven.”

The story of Wyatt morphing into a gunslinger went national, as well it should. It was crackling good copy. But it soon got a lot better.

With a warrant out for his arrest, Wyatt and his posse returned to Tombstone to hunt for the men who had helped Stilwell carry out Morgan’s murder.

Florentino Cruz, the lookout at Morgan’s killing, got the Full Stilwell. The posse chased him down and shot him to death, possibly after hearing his confession, and not the kind that brought forgiveness.

In the Republican, Wyatt said simply that he found Cruz and “left him stretched in his tracks.”

He also told the paper that he killed Apache Hank Swilling, another of the conspirators. But authorities never located a body, and historians can’t be sure what happened to Swilling.

Days after the Cruz hunt, Wyatt’s posse rode into a cowboy ambush at Iron Springs, where Wyatt nailed the appallingly drunk Curly Bill Brocius, who was left nearly in two pieces from Wyatt’s shotgun, and one of Bill’s confederates, Johnny Barnes, who died later.

That brought Wyatt’s count to four kills, and two possibles, if we count Swilling and Johnny Ringo, another mustache twirler that some contend Wyatt dispatched later that summer.

America’s newspapers gave extensive coverage to Wyatt’s savage vendetta, planting the seed of his legend, which in the coming decades would receive buckets of additional nourishment from biographers, newspaper hacks, saloon gossips, front-porch yakkers, television writers, moviemakers and so on.

It has flourished right up to today with Tucson’s belief that the Spanish Colonial Revival depot, and the planned Southern Arizona Transportation Museum, will make downtown a greater tourist draw.

The museum will sit just west of the current depot and have 1,000 square feet of exhibit space devoted mainly to railroad history.

The museum will include some recognition of the Earp-Stilwell dust-up, either in an exhibit inside the museum or on the grounds outside, says Howard Greenseth, vice president of Old Pueblo Trolley, a group partnering with the city on the project.

The latter might mean life-size bronze statues of Wyatt and Doc by sculptor Dan Bates.

Brotherly Loyalty

Does Wyatt deserve it? What a silly question. Of course not.

Over a life of 80 years, which ended in Los Angeles in 1929, he never did much of anything historically significant. He roamed around, played cards, cracked skulls in noisy cowtowns, played cards, shot Tombstone’s troublemakers, raced ponies, rarely talked freely about anything, prospected for gold and silver, played cards, almost never laughed, rolled dice and died poor, with—irony of ironies—two of Hollywood’s biggest cowboy stars among his pallbearers.

All of which explains why academic historians usually turn up their noses when it comes to writing about Wyatt, and a darn good thing, too. Otherwise, they would’ve scribbled him into obscurity because—let’s be honest—your average professor couldn’t write an interesting suicide note.

No, Wyatt’s myth has been built primarily by the unschooled, the unhinged and the unwashed, who, while lacking a full set of teeth and marketable job skills, can still, when the smoke blows away, spot a damn good story.

Here was a brave and stalwart marshal who, in spite of a few hiccups of illegality in his life—stealing horses in Arkansas, for one—followed the true course, until he had to choose between loyalty to his brothers and loyalty to the law.

As Wyatt told biographer Stuart Lake in the late 1920s, if he’d been willing to go outside the law earlier, Morgan would still be alive. “It’s a pretty high price to ask a man to pay for trying to shoot square,” Wyatt said.

It’s hard to argue the point. Every time Wyatt arrested one of the cowboy gang and brought them to court, they found friends to provide alibis and win their release.

It happened with Virgil’s ambushers and it happened with Morgan’s killers, and it would’ve kept happening because the cowboys weren’t going to stop until the Earps were dead.

So Wyatt chose his brothers.

He stepped outside everything he’d stood for and became a black-hearted killer who, in the mind’s eye, we see galloping out of Arizona Territory in the spring of 1882, smacking his horse with his hat and hollering, “Yaahhh!” as other law-dogs tried to run the fallen marshal down.

Now that, professor, is a story.

Beware a pale rider everybody. Wyatt’s coming back.