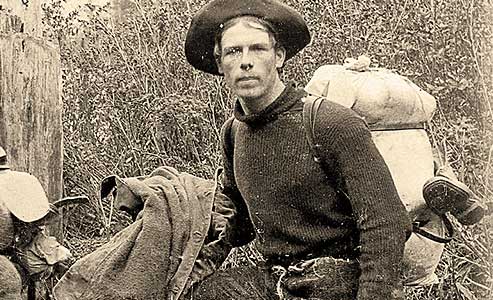

Jack London was only 21 years old when he stepped ashore in Alaska in 1897 to find his fortune in gold.

Jack London was only 21 years old when he stepped ashore in Alaska in 1897 to find his fortune in gold.

He looked boyish and threadbare, as did many who ventured north during a time when America was suffering from an acute economic depression. Skagway was a mob of naive gold seekers, with outlaw Soapy Smith ruling the town through a large ruthless gang. London wisely stayed clear of Smith and his scams that separated would-be millionaires from their money as they made their way to the Klondike.

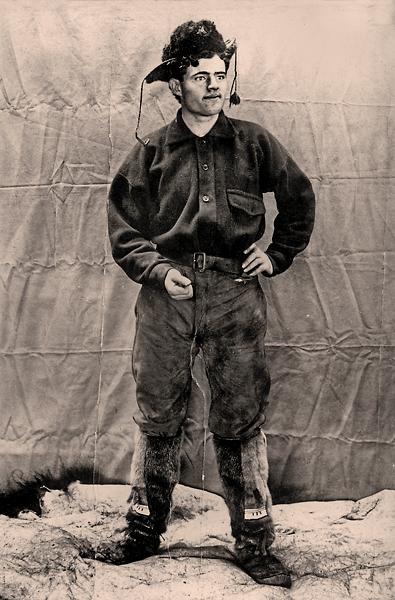

Hollywood has always done London an injustice. Movies portray him as an innocent when he arrives in Alaska, learning the ways of the world through the hard characters he meets there. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Abandoned by his astrologer father, William Chaney, just before he was born, he delivered papers, swept saloons and set up pins in a bowling alley before he turned to pirating commercial oyster beds at age 15. He then hired out to the California Fish Patrol, hunting down other pirates. At age 17, he shipped out to sea under a ruthless captain for Japan who became the background for his 1904 novel, The Sea-Wolf. The next year, he returned to San Francisco a confirmed socialist marching with Kelly’s Army of unemployed, although he dropped out before reaching Washington, D.C.; in New York, he was arrested for vagrancy and jailed for 30 days.

When he turned 21, he dropped out of college to make his living as a writer; he was starving when word came of gold for the taking in the Klondike. Only four days before the Umatilla sailed, his 62-year-old brother-in-law, James Shepard, grubstaked his trip north by mortgaging his home, but only if he could go too. London relented.

On July 25, 1897, the two sailed for Alaska. Onboard, they fell in with Merritt Sloper, a carpenter just returning from South America, Jim Goodman, an experienced placer miner, and a young Fred Thompson, who recorded their adventures.

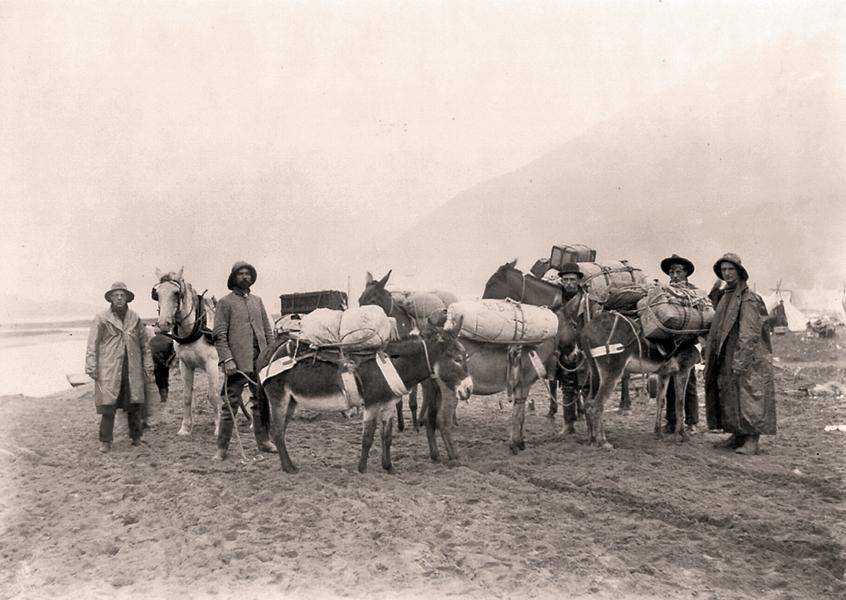

The five disembarked in Juneau on August 2 and three days later, with five tons of supplies, paddled canoes to Skagway.

The White Pass outside Skagway offered a horrific scene. “The horses died like mosquitoes in the first frost, and from Skaguay to Bennett they rotted in heaps,” wrote London of the Dead Horse Trail over White Pass.

Sickened by the sight and fearful of Smith’s men, the five paddled eight more miles to Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail.

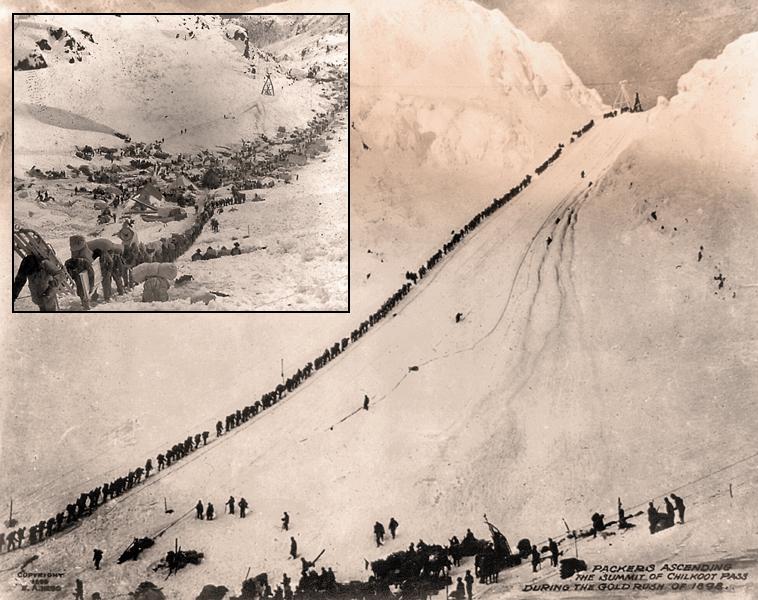

The Chilkoot Trail ascended 3,400 feet. Waiting at the summit were the North-West Mounted Police, checking to see that each prospector had adequate supplies before allowing them to enter Canada. London wrote, “I have 1000 lbs. in my outfit,” and he recalled carrying 150 pounds on the last stretch, portering it to the summit and waiting for it to be checked.

London and his comrades took 20 days to complete the task. The journey broke the health of his brother-in-law. “I give up,” said Shepard, after trying to scale the Chilkoot. “Go on without me. I’m catching the first steamer back to San Francisco.”

While portering supplies up the mountain slope, London saw a pair of shoes sticking out from a snowbank. He tugged at them, only to find them attached to a man still alive! An avalanche had just buried him only a few minutes earlier. The man credited London for saving his life.

The party reached Lake Lindeman in the Canadian interior on September 8. Sloper directed London and the others in building two 27-foot-long boats, the Belle of the Yukon and the Yukon Belle. They then portaged both boats and all their supplies overland to Lake Bennett, the headwaters of the Yukon River. They made the lake on September 22 with the nip of winter in the air. Soon, ice would form on the river. Between them and Klondike were two sets of murderous rapids. Mounties had placed men at both to retrieve the bodies of any who drowned.

London and his party shot through the Miles Canyon Rapids with the granite walls coming within six feet of the boats. They then walked back upstream to help Mr. and Mrs. Ret shoot down the same course. This second set of rapids nearly killed London and the rest.

Cocky, they found White Horse Rapids to be “a succession of foamy mountainous waves.” Yet a whirlpool captured their craft in its spin, nearly throwing them into the canyon walls. London lost control of the boat. Only by luck did the whirlpool shoot them out from its clutches. In spite of this near-death experience, London and Sloper again helped the Rets through the second set of rapids.

Fearful of being caught on the Yukon when the river froze up and hearing that Dawson had no vacant rooms, the party moved into abandoned cabins they found on Split-Up Island, near the mouth of Stewart River, on October 8.

A few days later, London traveled up Henderson Creek with Goodman, staking Claim No. 54. That site would be the scene for his short story “To Build a Fire.”

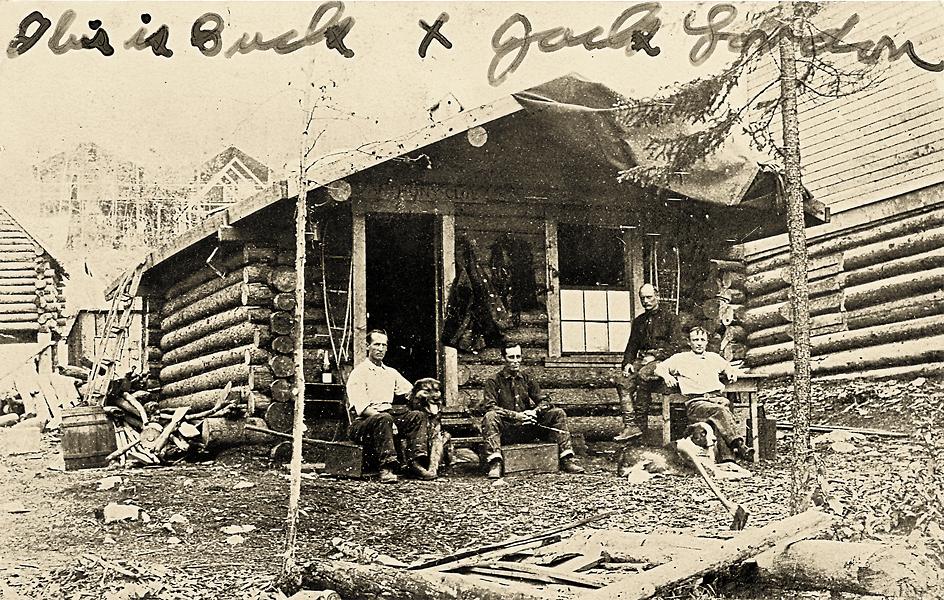

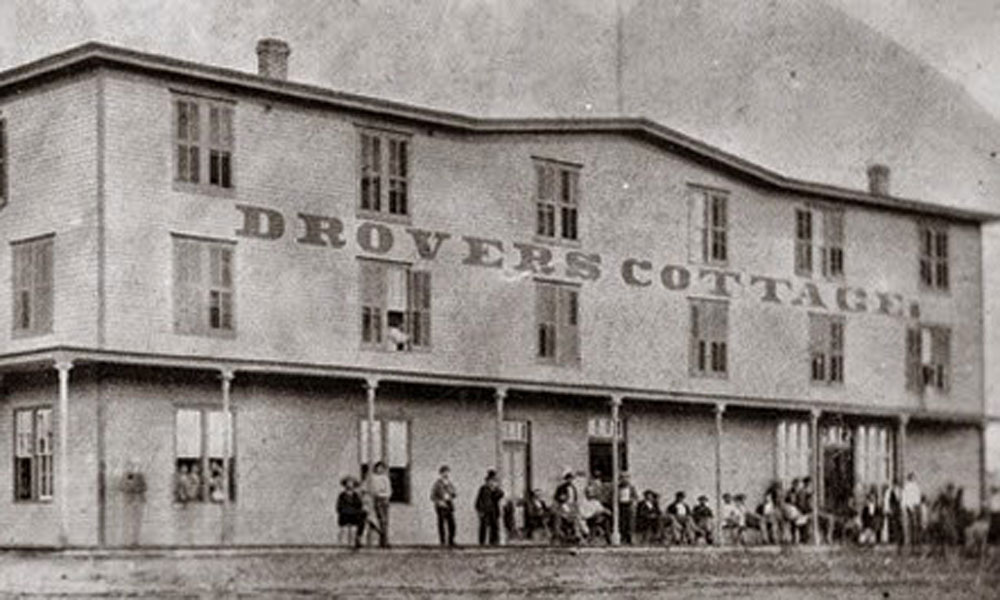

They then sailed on to Dawson, 70 miles downriver, to file gold claims and “whoop it up.” In Dawson, London met up with brothers Louis and Marshall Bond, and their St. Bernard and Scottish Collie mixed-breed dog named Jack. Jack was among many dogs labeled as the inspiration for Buck in London’s Call of the Wild. Canadian historian Pierre Berton claimed Buck was based on a dog owned by Belinda Mulrooney, owner of the famous Dawson hotel and saloon, Fairview, and hailed as the richest woman in the Klondike.

The charms of the Fairview and various watering holes kept London in Dawson for six weeks, listening to the tall tales of the millionaire Klondike Kings and to those who had gone bust. London waited too long. The Belle of the Yukon was now icebound. He and Thompson were forced to walk back to their cabin. By the time they arrived, temperatures were plummeting to 40 below. The party set up a routine of collecting ice, chopping wood and shoveling snow, as well as preparing the three Bs—beans, bread and bacon.

Their cabin became a social mecca for other snowbound prospectors who dropped by for a game of cards or to listen to London tell his stories of adventures at sea. One regular visitor, Bert Hargrave, described London as a chain smoker, telling yarns between puffs, and a debater while playing cards.

Cabin fever set in. The men became grumpy. One morning in November, London took Sloper’s ax to chop ice and damaged the blade. Sloper yelled at him, “Who do you think you are, you pirate! I’ll have your hide for this!” Sloper went for his rifle, but Thompson and Goodman held him down.

After that altercation, London moved in with Hargrave, Doc B.F. Harvey, an alcoholic surgeon, and a former judge named E.H. Sullivan. Now and then, he traveled upcountry to his claim, staying at Charley Taylor’s cabin. There, he carved into the wall, “Jack London, Miner Author Jan 27, 1898.” (The recently deceased Dick North helped rescue the London cabin in 1969.)

By spring, London’s gums were swelling and bleeding; he had loose teeth and dark spots were appearing on his dry skin. He was coming down with scurvy. In spite of being in pain, he helped Doc Charley build a new boat. Doc took the exhausted London downstream to Dawson’s St. Mary’s Hospital in May. The staff failed to cure the scurvy, and London decided he had better leave for home. He left with Taylor and John Thorson down the Yukon for a 1,500-mile voyage to the Bering Sea.

They sailed past abandoned towns and shot geese when they reached the swamp-like Yukon Flats. They dined on salmon from the river. Twice, they pulled in to watch American Indian dances. London jokingly jotted down that he believed the mosquitoes were now coordinating their attacks on him.

Arriving at Anvik on June 18, London ate his first vegetables he had eaten in nearly a year. Scurvy had caused his right leg to draw up against his body, horribly disfiguring him. He wrote that he was “now almost entirely crippled…from my waist down.”

By the end of June, they reached the port of St. Michael on the Bering Sea. London managed to ship out by shoveling coal on a steamer. “I brought nothing back from the Klondike but my scurvy,” he wrote. When he arrived in San Francisco, he learned his stepfather, John London, had died. The gold in his pockets amounted to $4.50. But the Klondike made Jack London into Jack London.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Library of Congress unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Huntington Library –

– Courtesy Huntington Library –