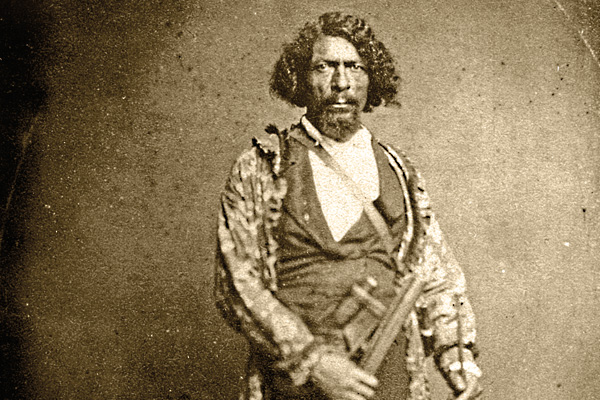

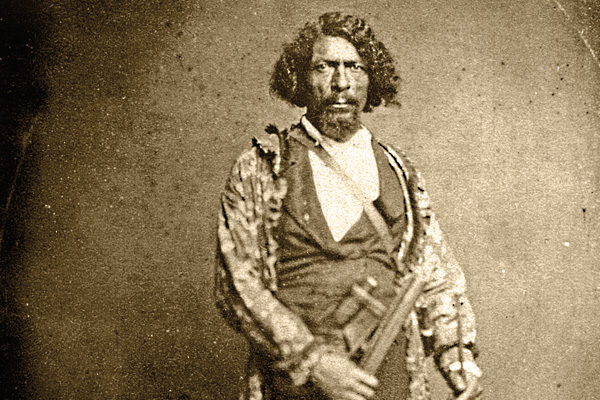

For most descendants of African slaves born prior to the Civil War, the path to freedom was usually a covert and perilous foot journey to exile in the North.

But for James Pierson Beckwourth, the trail blazed off the plantation and headed to the American West, into the Rocky Mountains, where he arrived as a fur trapper and, later, became an adopted member of the Crow Indians.

Beckwourth was most likely born in 1800 (historians have disproven the April 6, 1798 date) into American slavery, in Frederick County, Virginia, to a mixed-race slave mother and Sir Jennings Beckwith, a nobleman of Irish and English descent, and a major in the Revolutionary War. He was the third of her 13 children and raised as his father’s son. Beckwith moved his family to St. Louis when James was young and arranged for him to apprentice with a blacksmith.

When James was in his early 20s, Beckwith appeared in court and executed a Deed of Emancipation, granting freedom to the “mulatto boy,” giving the young man something of great value that would alter the course of his life.

After trips away from home, including a visit to New Orleans, James left his family in 1824 and signed up with Gen. William Ashley for a trapping expedition headed to the Rockies. For 12 years, James lived the isolated, rugged life of a frontiersman, befriending many of the renowned mountain men of the day, and attending the very first Mountain Man Rendezvous in 1825 on the Green River at Henry’s Fork.

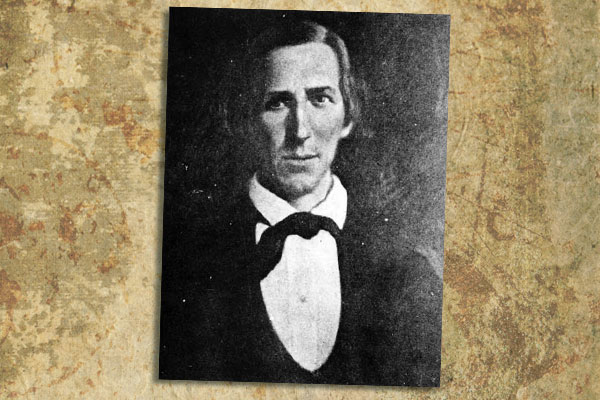

Many of the details about Beckwourth’s life originate from an autobiography he dictated in 1854-55 when he was in the goldfields of California. An impoverished justice of the peace, Thomas D. Bonner, edited the rambling prose and The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth—Mountaineer, Scout, and Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians was published by Harper & Brothers in 1856 in New York and London. A French edition was published in 1860.

His eyewitness role in 19th-century American history was cavalierly discredited by some historians, transparent in their prejudice of a “mongrel of mixed blood.”

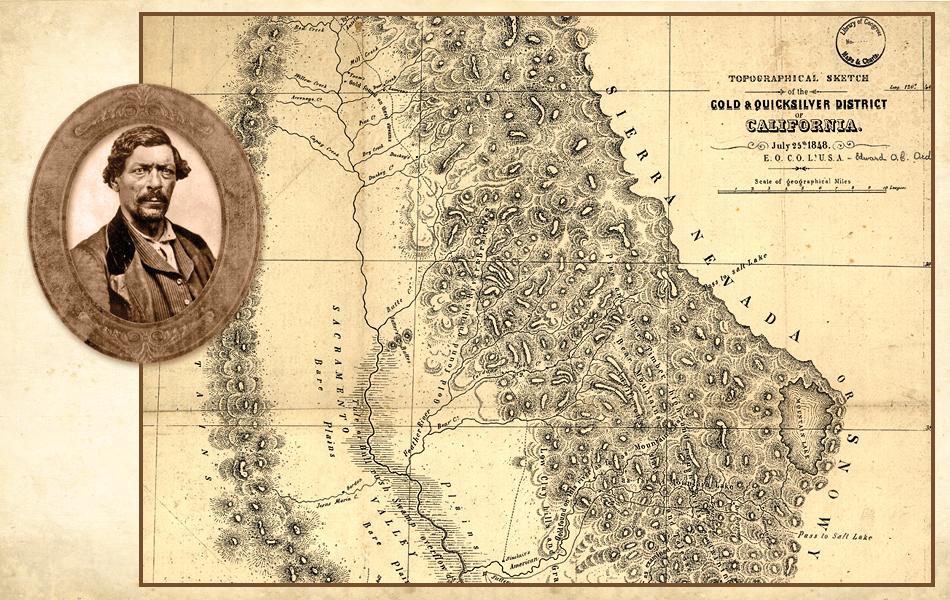

But life in the frontier West is robustly conveyed in Beckwourth’s autobiography. He chronicled the American frontier’s fall from innocence and the role played by alcohol, disease, massacres, war and the clash of cultures. He witnessed the rise and ruin of fur trapping, the Crow Indian culture, and California’s gold rush. He also recounts how in 1850-51 he built a trail over the Sierra Nevadas, and then led the first settlers’ wagon train on the Beckwourth Trail in 1851 from near Reno, Nevada, to Marysville, California.

Finally settling in Denver as a storekeeper and Indian scout for the Army, Beckwourth died of unknown causes after guiding a military column from Fort C.F. Smith, Montana Territory, to a Crow village near the Bighorn River on October 29, 1866.

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer. Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details to stuart@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy True West Archives/Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –