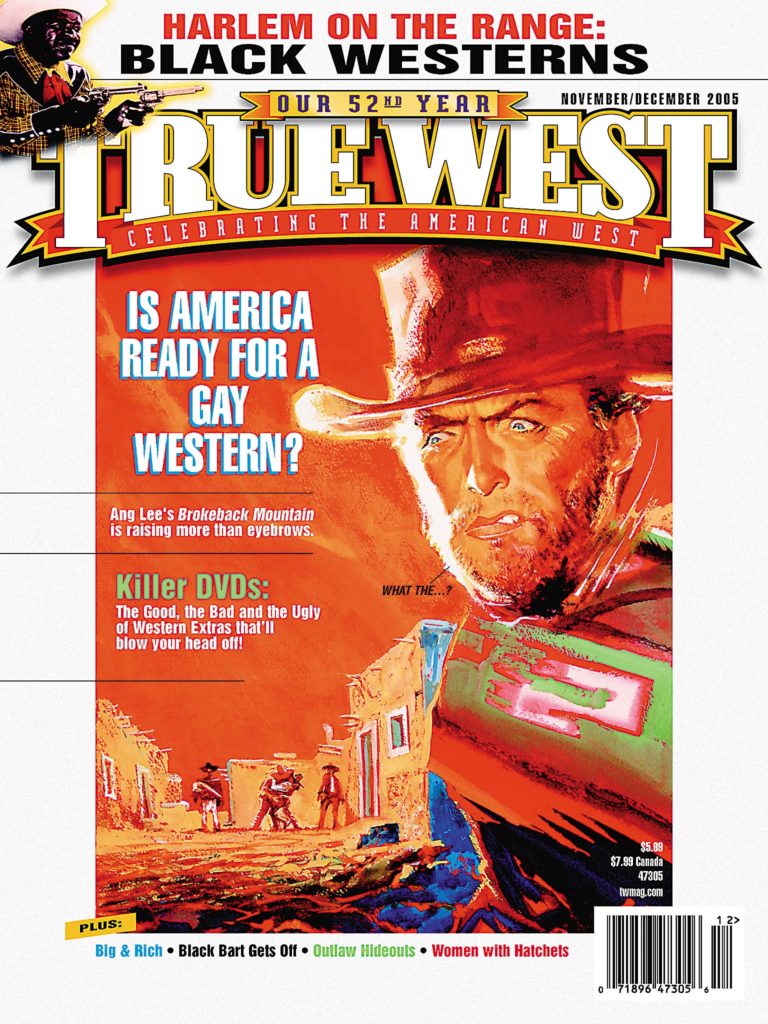

They were the trailblazers of their day—a visionary group of actors, writers, directors, producers and businessmen whose stage was the old Negro Cinema.

They were the trailblazers of their day—a visionary group of actors, writers, directors, producers and businessmen whose stage was the old Negro Cinema.

Born of both necessity and opportunity, the “segregated cinema” created by these entertainment pioneers operated for four decades, bringing to movie houses an array of films predominantly made by and for African Americans.

From 1916-50, the Negro Cinema turned out over 500 pictures, including mysteries, comedies, musicals, serials, documentaries, gangster flicks and, yes, Westerns. The latter, of course, have proven to be among the most culturally interesting, bearing telling titles such as A Chocolate Cowboy, Two Gun Man from Harlem, The Bronze Buckaroo, Black Gold and Harlem Rides the Range.

Black Star Rising

Black Americans had been involved in the motion picture industry from the beginning. From 1900-12, entrepreneur C.E. Hawk, along with other blacks, had toured the southeastern United States, exhibiting the latest films from the burgeoning movie business, then located primarily on the East Coast. During that same period (the exact year is unknown), Edward Lee opened the doors of the first black-owned movie theater in the United States at 13th and Walnut Streets in Louisville, Kentucky.

In the ensuing years, black Americans took on an even greater presence in the

film industry. The year 1913 witnessed

the founding of the Foster Photoplay Company in Chicago, which was the first black-owned motion picture production and distribution entity. In 1916, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company was established in Los Angeles by black film pioneers Noble Johnson, Dr. J.T. Smith and Clarence Brooks. Lincoln’s first movie, Realization of a Negro’s Ambition, was released later that year.

Harlem heads West

Westerns occupy their own small niche in the Negro Cinema. More than a dozen black-cast, Western-theme features were made between the years 1916-1950, according to Henry T. Sampson’s seminal, 1995 book, Blacks in Black and White.

The first black-cast Western may well be Trooper of Company K, which was released by the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in late 1916. Directed by Harry Gant and starring Noble M. Johnson as “Shiftless” Joe, Beulah Hall as Clara Holens and Jimmy Smith as Jimmy Warner, this film examines the life of a young black man who enlists in the U.S. Army and later serves with the all-black Tenth Cavalry (commanded by white officers) near Casas Grandes, Mexico. The Tenth then sees action against Mexican troops at the Battle of Carrizal on June 21, 1916, where the lead character, “Shiftless” Joe, distinguishes himself in combat when he rescues his wounded captain.

Filmed in California’s San Gabriel Valley, Trooper of Company K (a.k.a. A Trooper of Troop K) had quite a realistic aura to it, as many of the troopers or “buffalo soldiers” seen in the picture were either current or former members of the famed Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, which boasted of the best horsemen in the American Army. In addition, many of the Mexican soldiers used in the film had previously fought during this era when U.S. troops had been conducting operations south of the border in pursuit of the notorious Mexican bandit, Pancho Villa.

“The Trooper of Company K will rank as an exceptional picture if only for its historical value, commemorating as it does the battle of Carrizal, where our boys made such a good fight against overwhelming odds, sacrificing their blood and life for their country,” reported the black-owned newspaper The California Eagle in its October 10, 1916, review.

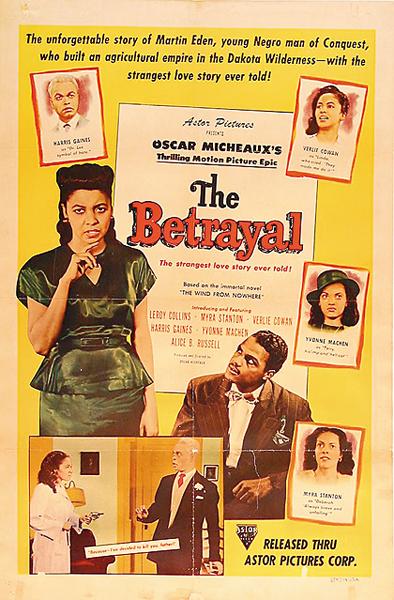

In 1919, the Micheaux Film Corporation brought to the black cinema The Homesteader, a film based on the Oscar Micheaux novel of the same title. Illinois-born Micheaux (1884-1951) was one of the giants of the Negro Cinema, whose quality movie work (over 30 feature films as a producer alone) is duly recognized by entertainment historians today.

Written and directed by Micheaux and starring Charles D. Lucas, Evelyn Preer, Vernon S. Duncan and Iris Hall, The Homesteader was a love story set in the wilderness of the Dakotas, with Lucas playing the title role of a black homesteader named Jean Baptiste. The movie, made for an estimated $15,000, was shot on location in Winner, South Dakota.

“The Homesteader is not a sensational picture or story as western stories go,” reported the black-owned newspaper the Chicago Defender in its February 22, 1919, review, “but it is the story of the west as it is, a theme that proves educational as well as interesting.”

The year 1921 witnessed the release of The Crimson Skull by the Norman Film Manufacturing Co. of Jacksonville, Florida. This big black-cast Western thriller of its day featured principal stars who were two of the Negro Cinema’s most celebrated performers, Anita Bush and Lawrence Chenault. The film also showcased the “World’s Champion Wild West Performer” Bill Pickett, “the one-legged marvel” Steve Reynolds and “30 Colored Cowboys” in support, as the promotional material blared.

R.E. Norman, the white owner of Norman Film, was apparently interested in producing a realistic cowboy picture, according to a September 7, 1921, letter, which he addressed to George P. Johnson of the black-owned Lincoln Motion Picture Company: “We are producing a couple of Western pictures in Oklahoma with an all-colored cast and are in need of female talent with riding ability for cowgirl parts…. We can also use a good Mexican character for heavy and would appreciate you putting us in touch with other colored talent having real merit.”

The Crimson Skull was filmed in the all-black city of Boley, Oklahoma, whose citizens provided the background for this six-reel silent. At the time, Boley was a thriving prairie town, boasting of its own electric plant, a modern water works, a national bank and, according to one newspaper, “ranchers who owned their own mounts and could ride like the wind.”

The Crimson Skull was a story of Western justice. When the community is threatened by an outlaw gang known as “The Skull and his Hooded Terrors,” the concerned townsmen organize “The Law and Order League,” which promptly fires the toady sheriff and replaces him with Lem Nelson, the fearless owner of the Crown C Ranch. Aiding Lem in his new duties is Bob Calem, foreman of the Bar L, who infiltrates the secret outlaw band.

In its film review, the black-owned Cleveland Gazette called The Crimson Skull “a virile breath of the golden west,” duly noting that “Bill Pickett, our veteran world’s champion bulldogger, proves that he is one of the greatest trained riders and ropers that the west has produced and does stunts that call for real skill.”

In 1923, the Micheaux Film Corporation released The Virgin of the Seminole. Shot in Roanoke, Virginia, and starring William Fountaine, Louise Borden and Shingzie Howard, this picture was set in the Northwest and the Southeast, where it chronicled the adventures of a young black man who earns his spurs with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Later, thanks to a huge reward collected in a gun battle with an outlaw, the ex-Mountie buys a spread and becomes a successful rancher.

Also in 1923 came Norman Film’s The Bull-Dogger, one of the Negro Cinema’s most famous pictures, “featuring Bill Pickett, the black hero of the Mexican bull ring, in death-defying feats of courage and skill, such as wild horse racing, roping and tying wild steers,” so reported the movie’s official press book. Joining Pickett in the cast were his fellow Crimson Skull performers, Anita Bush and Steve Reynolds. The renowned Pickett (1870-1932)—also known as “The Dusky Demon”—was the originator of bulldogging (wrestling a steer to the ground and biting its lip in order to subdue it) and later became the first black to be inducted into the National Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1971.

One year later came Monarch Productions’ The Flaming Crisis, which starred Dorothy Dunbar, Calvin Nicholson, Henry Dixon and Talford White in a story of outlaw gangs set in the Southwest. Said reviewer Carl Beckwith in the black-owned newspaper, Kansas City Call (May 30, 1924): “A word of well-earned praise can be said for every member of the cast, even down to the hard-working cowboys, who furnish the atmosphere. The Flaming Crisis should set a standard for other productions in the future—interesting, well-acted and carefully directed.”

In 1925, a notable black Western comedy short titled A Chocolate Cowboy was released to theaters by Cyclone. Produced by William M. Pizor, it starred Fred Parker and Teddy Reavis. Parker would later appear in a number of other mainstream Westerns, including Riders of the Rio (1930), The Rawhide Terror (1934), Wild Horse Canyon (1938) and Prairie Gunsmoke (1942).

On May 7, 1928, Black Gold, another fine picture from Norman Film, made its debut in New York City. Promising “Action! Love! Thrills!,” this movie featured Laurence Criner, Kathryn Boyd, Steve Reynolds, Alfred Norcom and real-life U.S. Marshal E.B. Tatums in a modern-day Western set among the oil fields of Oklahoma.

The Black Roy Rogers

In 1937, the 6’7” multiracial, big-band singer Herb Jeffries, born September 24, 1911, in Detroit, cast himself as cowboy crooner Jeff Kincaid in Associated Features’ Harlem on the Prairie—the first black-cast musical Western. Jeffries, with his rich baritone voice, had started his musical career as part of a trio, singing as a teen

in his hometown. With a letter of re-commendation from the great Louis Armstrong, Jeffries then found work with Jazz musicians Erskine Tate, Earl “Fatha” Hines and the legendary Duke Ellington.

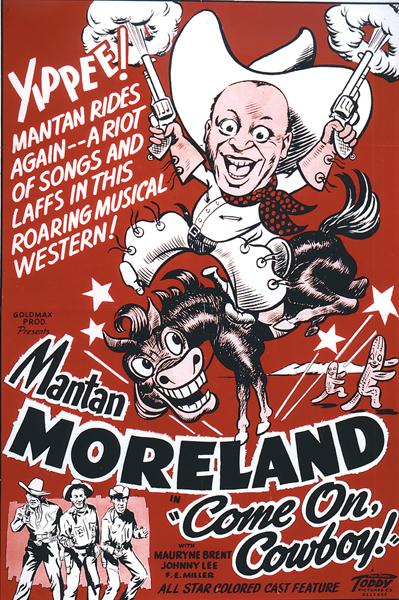

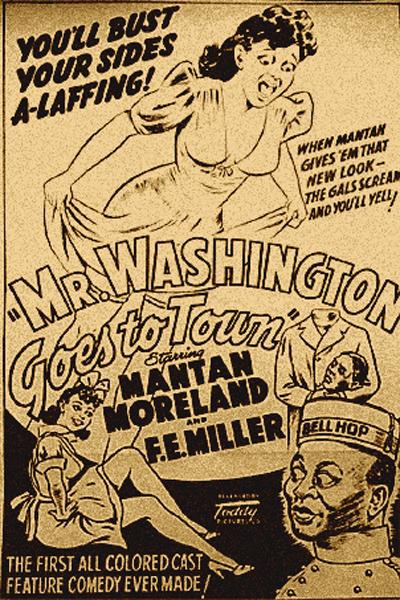

Produced by Jed Buell, Harlem on the Prairie also featured bug-eyed comic actor Mantan Moreland, Spencer Williams (who later starred as Andrew Hogg Brown on TV’s Amos ’n’ Andy, 1951-53) and two musical groups, the Four Tones and the Four Blackbirds. Songs heard in the film included “Romance in the Rain,” “Old Folks at Home,” “Albuquerque” and “A Range in Heaven.”

Jeffries, whom many black youths thought of as their very own black Roy Rogers, went on to star in three more musical Westerns: Two Gun Man from Harlem (1938), The Bronze Buckaroo (1939) and Harlem Rides the Range (1939). The Bronze Buckaroo, with Jeffries as Bob Blake, the Singing Cowboy and Lucius Brooks as his sidekick Dusty, was filmed at the all-colored N.B. Murray’s Dude Ranch in Victorville, California. Catching The Bronze Buckaroo at the Apollo Theater in New York City was Duke Ellington, who later hired the singing black cowboy for his orchestra, where Jeffries performed the band’s big hits “Flamingo” and “Satin Doll.”

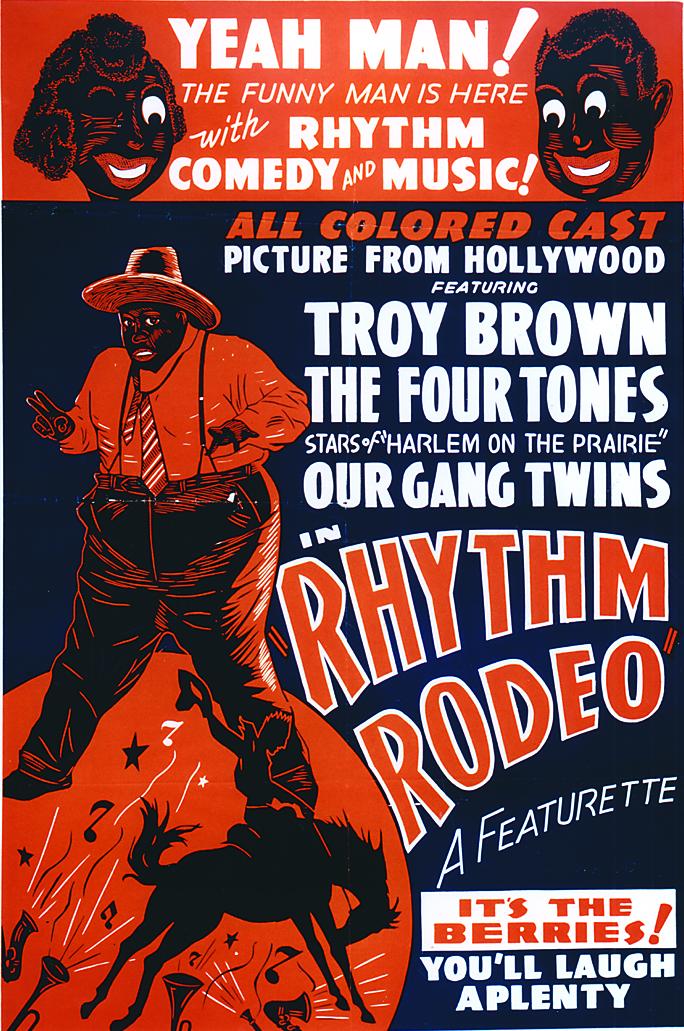

Other black-cast musical Westerns were also produced by the Negro Cinema. From 1938, there’s Rhythm Rodeo, an “all colored cast picture from Hollywood,” which features Troy Brown, Jr., the Four Tones (Lucius Brooks, Rudolph Hunter, Leon Buck, Ira Hardin) and Our Gang Twins.

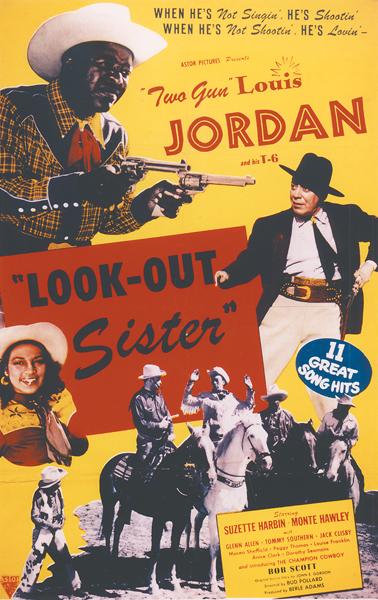

From 1948, there’s Astor Pictures’ Look-out Sister, featuring big-band leader Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five along with a stunning revue of Hollywood beauties. Made for $60,000, Look-out Sister was set mainly at a modern dude ranch and featured Jordan, with assistance from saxophonist Paul Quinichette and pianist Bill Doggett, singing numbers such as “My New Ten-Gallon Hat” and “Jack, You’re Dead.”

The old black-cast Oaters eventually gave rise to a new breed of black Westerns decades later during Hollywood’s “blaxploitation” era. They included fare such as Buck and the Preacher (1972), The Legend of Nigger Charley (1972) and Adios Amigo (1976).

William J. Felchner is a graduate of Illinois State University. His articles have appeared in Frontier Times, Old West, Persimmon Hill, Hot Rod, Military Trader, Western & Eastern Treasures and Corvette Quarterly.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Robert Brosch Archival Photography; Allen Park, Michigan –