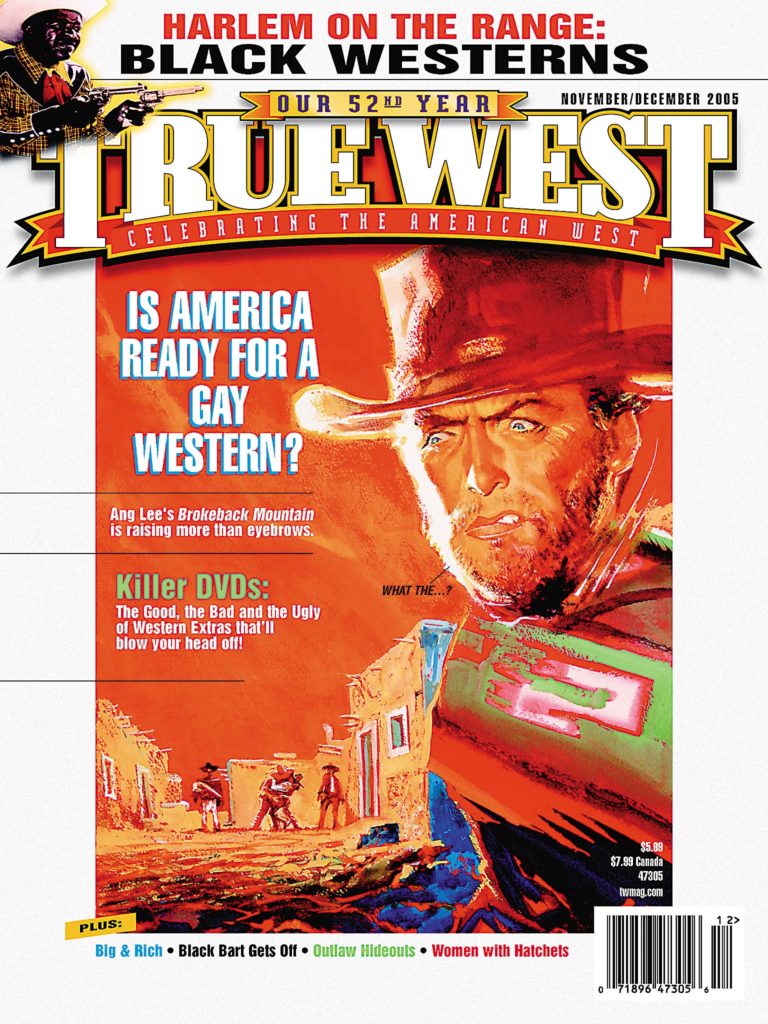

Last year marked the first time since Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves (1990) that a Western was at the center of a broad and often contentious debate.

Last year marked the first time since Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves (1990) that a Western was at the center of a broad and often contentious debate.

When HBO launched its series Deadwood, critics and Western fans engaged in heated arguments over its profanity and violence.

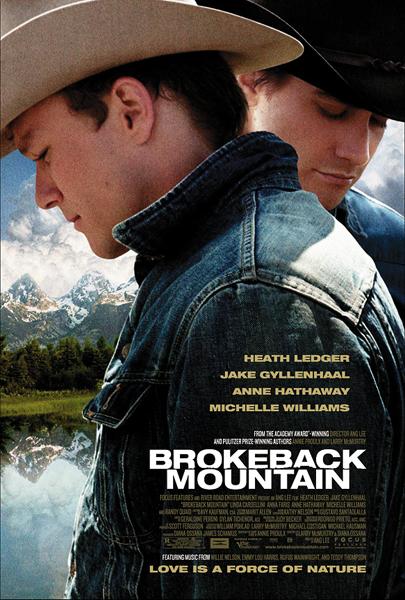

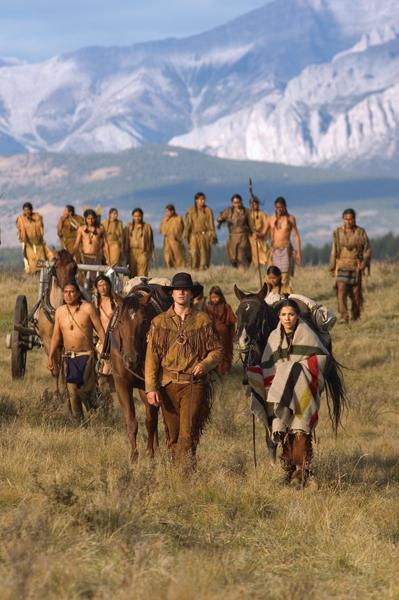

This year we have not only Deadwood’s second season to contend with, but two other Westerns that have raised eyebrows: TNT’s summer miniseries Into the West, an ambitious project committed to giving a balanced view of America’s Western experience, and Focus Features’ Brokeback Mountain, a gay-themed modern Western featuring a 20-year love affair between two cowboys, played by young heartthrobs Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger (read our feature on gay heritage in the West, p. 41).

Are these true Westerns in the sense

that they explore moral issues and “do the right thing,” or distortions of a beloved genre pandering to the lowest com-

mon denominator or “politically correct” sensibilities?

Decisions of moral conscience have always been pivotal to Westerns, both as they further the plot and, particularly, define heroism. Not always easy to watch, however, these decisions can challenge audiences to question accepted views and practices. In fact, the Western has a long tradition of tackling controversial social issues—McCarthyism, racism, war, violence—and filmmakers have often been criticized for their efforts. When Gary Cooper threw his marshal’s badge in the dirt at the end of High Noon (1952), John Wayne called it the most un-American thing he’d ever seen. Fifteen years later, a New York Times reviewer described anyone who would voluntarily sit through The Good, the Bad and the Ugly as “not someone I should want to meet, in any capacity, ever.” Looking back at Dances With Wolves and even Unforgiven, we can see filmmakers taken to task by those who saw them advocating a certain point of view.

But these and other controversial Westerns advance the genre by crossing new boundaries. Focusing on difficult moral dilemmas or creating less than savory heroes, they set the bar ever higher. In their multifaceted characters and social relationships, in their poignancy and jarring storylines, they touch a cord and often draw broad and diverse audiences. The most controversial Westerns of 2005, Deadwood, Into the West and Brokeback Mountain, may make some viewers uncomfortable, but they are pushing the edge of the genre, forcing audiences out of the comfort zone of a man on horseback sacrificing for the good of the community into the realm of true human existence that is never black and white, but always various shades of gray.

Deadwood is a mastery of complexity and extremes. The lure of opportunity and adventure is undermined by the realities of despair and exploitation. Despicable acts of violence are set in contrast to small acts of kindness. Sheriff Seth Bullock, the moral man with rage in his heart, is juxtaposed to saloon owner Al Swearengen, the vicious opportunist who recognizes the importance of moral order. A new bicycle is the source of great fun and amusement one week, but the catalyst of an accidental trampling and death of a young boy the next. Swearengen and his crew can be disgusted at the treatment of Chinese prostitutes who are kept in outdoor cages, but in the next breath, they supply “chinks” to Hearst mining interests at half the price of what the San Francisco “chink” currently offers.

We may bemoan this no-holds-barred approach, but Deadwood reminds us that the history of the Old West is not always a pretty one. “Things should be told accurately,” says Dave Baldwin, executive vice president of Program Planning at HBO. “I think if you’re going to portray a moment in time, you need to do it right.”

And HBO is not alone in believing so. TNT’s Into the West offers a similarly stark vision of our frontier history. Producer Steven Spielberg, drawn to the drama of the Old West, describes the miniseries as “the clash of cultures and the eventual overwhelming of one nation’s way of life over another.” Spanning the 19th century, from its early years of trailblazing mountain men to its close with the massacre at Wounded Knee, Into the West chronicles the experiences of two families: one Native American, one white. The miniseries, billed as the story of both sides of the conflict, is decidedly pro-Native American in its stance, particularly by the third of its six installments. “As you watch the entire series,” says Director Jeremy Podeswa, “you really get the sense of the profound, sad near-destruction of a culture.” Into the West ends on a rather syrupy note—“even though the culture may have been overwhelmed,” Podeswa adds, “the spirit of the people has survived”—but the miniseries is a powerful reminder of a tragic and brutal history that is all too easily ignored.

Ending 2005 with a bang is Brokeback Mountain, due out in December. Described by Director Ang Lee as a “great American love story,” the film is already winning fans who awarded it the top prize at the Venice Film Festival (held this past September).?This story of ill-fated love set against the magnificence of Western landscape is hardly a new one, except for one thing: the lovers at the center of this film are two men. In their struggle to fight the yearning they have for one another, we see the pain and consequences of prejudice and hatred, from robbing someone of a life fulfilled to extinguishing that life altogether. While a small budget film by Hollywood standards, Brokeback Mountain boasts an impressive pedigree: directed by Academy Award-winning Director Ang Lee and coscripted by Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Larry McMurtry from a short story by another Pulitzer Prize winner, Annie Proulx. The studio, Focus Features, which has produced award-winning films such as The Pianist, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Lost in Translation, is positioning Brokeback Mountain to be in the running for this year’s Academy Awards.

The Western, as a genre, is about many things: perseverance, courage, dogged determination. But at its heart, the Western is about survival. It is about life at its most basic, stripped of all social comforts and safety nets. It is about longing and loss. Spare and raw, Westerns expose the extremes of human emotion and behavior.

All three Westerns give us examples of extraordinary valor, but also unspeakable brutality; victory against insurmountable odds, but also crushing defeats; elation at even simple accomplishments, but also devastation at life’s injustices. They show that we continue to look to Westerns to give us what we have always loved about the genre—a genuine human experience.

Those of us who have enjoyed Westerns all our lives wonder where the next generation of fans will come from. People under 50 didn’t grow up with Westerns. Many have never even heard of Roy Rogers or Gene Autry or Hopalong Cassidy. But these new Westerns are finding a broad-based following, both among older as well as younger viewers. Deadwood’s audience, according to HBO’s Dave Baldwin, “is a very different [one] than watched the theatricals and the movies Turner Broadcasting has put on. Our audiences tend to be a bit younger and more female as well.” Brokeback Mountain, with its cast of 20-something stars and a timely topic, could very well draw the same.

The year 2005 may mark a resurgence for Westerns, as 2006 promises to give us even more. Among others, we’ll see the third season of Deadwood, Tim McGraw’s Flicka, Robert Duvall’s miniseries Daughters of Joy, Brad Pitt’s The Assassination of Jesse James and Jon Voight’s September Dawn, a dramatization of the 1857 Mountain Meadows massacre of a wagon train by a renegade Mormon band.

The Western dead? That’ll be the day.

Yardena Rand is a member of the Western Writers of America and the author of Wild Open Spaces: Why We Love Westerns. Please visit www.ilovewesterns.com for more information.

Photo Gallery

Brokeback Mountain breaks the mold.

Is America ready for gay cowboys? Brokeback Mountain’s producer James Schamus is hopeful. “Even though we think of this as a very polarized country on this subject,” he says, “we’re less polarized than the media would lead us to believe. These stories are very American. We all know someone in this situation. It’s a story that could literally happen anywhere.”

This universality, along with the fact that no major studio has ever tackled this issue, has given Brokeback’s filmmakers the opportunity to stretch not only the bounds of Westerns, but of romance dramas as well. “Hollywood love stories have become the story of my $25 million corporation kissing your $17 million corporation,” adds Shamus, “not a lot of tension or surprise. Here’s a movie about genuine love, genuine consequences, genuine stakes. That’s a rarity today.”

Damon Romine, Entertainment Media Director for the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, believes audiences will come to see the film because of its power. “Whatever a film’s subject matter,” he says, “people show up to be entertained and to see a great story. Love between two people is universal.” Bottom line, though, is the film’s honest treatment of gay relationships, something he embraces. “I’m encouraged by the movie posters (see above) with Heath and Jake and the tagline ‘Love is a Force of Nature,’” he adds. “They’re not shying away from the fact that at the heart of this story is the relationship between these two men.”

– Courtesy Focus Features / By Kimberely French –

– Courtesy HBO Deadwood / By Preshant Gupta –

– Courtesy TNT / By Chris Large –