General Santa Anna ordered every single Texan prisoner executed—men, fighting for the Republic of Texas.

General Santa Anna ordered every single Texan prisoner executed—men, fighting for the Republic of Texas.

A total of 214 of them had been captured in December 1842 on the south bank of the Rio Grande in Mier, Tamaulipas, Mexico. The Mexican Army then marched them south to Salado, where the Texans decided they had gone “far enough if not too far into the country.”

The Texans had been retaliating for Mexican attacks around San Antonio, known then as West Texas, and the capture of their fellow Texans by Mexican Gen. Adrian Woll’s 1,400-man army, which seized the city on September 11, 1842. Alarmed by the invasion, Texans rushed to form volunteer militias. Texans under Gen. Alexander Somervell soon marched south, capturing Laredo and Guerrero, but abandoned their mission on December 19, 1842, when the general decided it was too late to catch Woll. About 300 men refused to retreat and instead crossed the Rio Grande River on Christmas Day and attacked the Mexican border town of Mier. Even though they had lost only 30 men to the Mexican’s 600, the Texans surrendered because they were low on ammunition.

After spending almost two months in prison, the Texans escaped on February 11, 1843. The escapees disarmed 150 Mexican infantrymen, killed a number of guards, stole horses and put the Mexican cavalry to flight.

Unfortunately, most of the Texans then got lost. Bigfoot Wallace described their plight under the scorching sun: “the suffering of men became so intolerable that many of them, to relieve themselves of all superfluous weight, threw away their guns and equipment…. Many of the men gave out entirely, and laid down by the wayside to die…. Still the rest of us struggled on, hoping that our strength might hold out until we came to water.”

They finally got their drink of water, but it was after accidentally wandering into a camp of Mexican soldiers. Within days of their escape, 176 Texans were recaptured and sent back to prison, where they learned of Mexico President Santa Anna’s wrath.

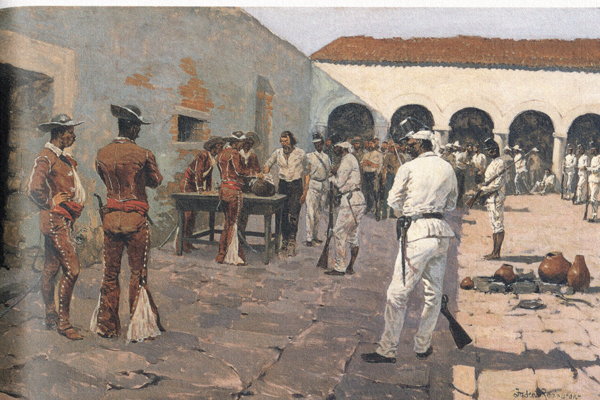

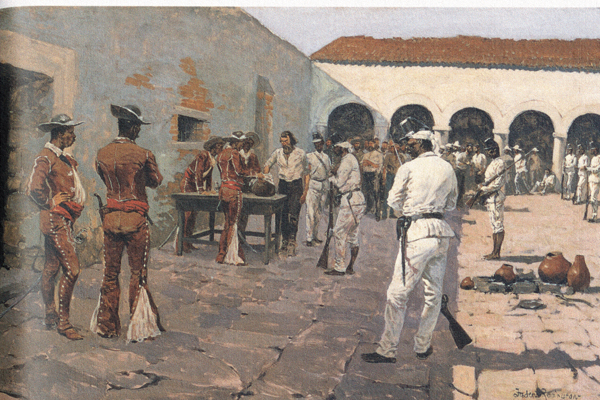

The Bruce of the West

But luckily for some, Coahuila Gov. Francisco Mexia refused to carry out Santa Anna’s ordered execution, and several foreign ministers to Mexico got the decree modified to more humane terms: that only one man in 10 be executed. In an earthen pot were placed 176 beans—159 white and 17 black. Prison commander Col. Dominic Huerta had the Texans chained in pairs and blindfolded. They were marched out as an officer approached with the olla containing the beans. For a few moments, the Texans stood silent, and then the drawing began.

The jar was held up, so no one could see inside. The officers drew first. Eager to kill Capt. Ewen Cameron, once hailed as the Bruce of the West, the Mexicans had put all the black beans on the top, and made Cameron lead off. They had a reason to want the Scottish-born Cameron dead: he was the kind to persevere.

During the battle at Mier, when the Mexican soldiers had charged at Cameron, he emptied his rifles into them and then threw rocks, forcing the soldados to take cover until he could reload.

During the second day of fighting, a majority of the Texans voted to surrender and laid their guns in the street. Cameron, however, rushed back to his position and urged his men to keep fighting. Some 50 of them stood their ground. Cameron’s unit held its position until Cameron saw that all hope was gone. He looked around at his men and said, “Boys, it is no use for us to continue the fight; they are all gone but us.” Only then did he break his sword and surrender.

So the Mexicans knew Cameron was tough.

“Better luck next time”

But now one of Cameron’s men suspected the Mexicans had rigged the beans against Cameron. So, when Cameron approached the jug, he was warned, “Dip deep, Captain.” Cameron plunged his hand to the bottom and pulled out a white bean. The Mexicans were disappointed.

The rest of the drawing was done in alphabetical order and went rapidly. Although the men knew that 17 of them would die, they could not help showing their joy as friend after friend drew a life-saving white bean.

And they showed their sorrow, too, as someone who had fought beside them drew a black bean. To these unfortunates, the Mexicans sarcastically wished them “Better luck next time.”

As the list dwindled down to the W’s, there were two black beans and four white beans left.

Bigfoot Wallace, who’d rushed to Texas after losing a brother and cousin in the Goliad Massacre, had been watching as the beans were drawn, and he thought that the black beans were a little larger than the white ones. When his turn came, he scooped up two beans and felt them between his fingers while a Mexican officer told him to hurry up. Wallace finally dropped one bean and pulled out the other. It was white.

The next two men to draw, Martin Wing and Henry Whalen, both drew black beans. Those were the last of the black beans, and the final three men on the list did not draw. The condemned men were immediately separated from the others and given a chance to write home.

The Surprise “Deaths”

After drawing a fatal bean, Whalen reportedly said, “Well, they don’t make much off me, anyhow, for I know I have killed twenty-five of the yellow-bellies.” Whalen then asked the Mexicans for a good last meal, saying, “I do not wish to starve and be shot too.” Surprisingly, the Mexicans gave him a double ration, which he ate with great enjoyment and then declared himself ready to die.

At about 6:30 p.m. on March 25, 1843, nine of the condemned were chained together and shot. The remaining eight were then executed in the same manner. In all, the killing took roughly 11 minutes.

Henry Whalen “received fifteen shots before life was extinct” and continued cursing the Mexicans until someone blew out his brains with a pistol.

The following morning, as the Mexicans prepared to bury the bodies in a mass grave, one corpse was discovered missing. Seventeen-year-old James L. Shepherd had been only wounded, and under cover of darkness, escaped. Three days later, he was captured in Saltillo and fatally shot.

Chained to Fate

The remaining Texans left Salado on March 26, first marching to San Luis Potosi and then toward Mexico City.

On April 24, the prisoners arrived at Huehuetoca. On Santa Anna’s orders, Cameron was taken from his companions at midnight and shot the next morning.

When the prisoners arrived in Mexico City, they were compelled to build a four-mile road to Santa Anna’s palace at Tacubaya. They spent six months completing the road, before being moved to Santiago Prison and then back to Perote Prison.

For 18 months, Santa Anna teased Texas President Sam Houston with the prisoners, first offering to free them, and then finding some new reason to keep them in chains. On September 12, 1844, Santa Anna finally issued an order for their release. Of the 261 men who had fought in Mier, 84 died, 35 escaped and 142 were eventually set free.

Former prisoner Thomas Jefferson Green moved to California in 1849 and served in California’s first Senate, sponsoring the bill that created the University of California. He later became major general in the California militia.

Bigfoot Wallace had a long, distinguished career as a scout and Texas Ranger.

Samuel Walker joined Jack Hays’ company of Rangers in 1844. During one fight, Walker and 14 other Rangers used the new Colt Paterson revolvers to successfully defeat 80 Comanches. Walker then joined Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army as a scout, fighting in the battle of Monterrey in September 1846. In October, he visited Samuel Colt, proposing improvements, including a fixed trigger and guard, to Colt’s Paterson revolver. The new six-shooter was aptly named the Walker Colt.

As for the condemned men, one of them, James Masterson Ogden, left behind a farewell letter that speaks to the courage of the Texas soldiers.

“Tell my mother not to grieve for me,” he wrote, “for the friend that I love is with me and my God will not forsake me.

“Give my love to all . . . and tell them to meet me in heaven.

“I am indebted for the favor of dying with my hands untied. Farewell, all farewell.”