“Far away from my wife and child, and six hundred miles of constant danger in an uninhabited region was not a pleasant prospect for contemplation,” Santa Fe Trail traveler Hezekiah Brake noted in 1858. “But I laughed with the rest, joked about roasting our bacon with buffalo chips, and the enjoyment we would derive from the company of skeletons that would strew our pathway.”

“Far away from my wife and child, and six hundred miles of constant danger in an uninhabited region was not a pleasant prospect for contemplation,” Santa Fe Trail traveler Hezekiah Brake noted in 1858. “But I laughed with the rest, joked about roasting our bacon with buffalo chips, and the enjoyment we would derive from the company of skeletons that would strew our pathway.”

It doesn’t seem so bleak these days.

The Santa Fe National Historic Trail is well inhabited, especially in Central Missouri. I can have the cook at a greasy spoon roast my bacon on a gas stove instead of buffalo chips, and few skeletons are strewing my path—most of the folks look a little pudgy (probably from the barbecue and beer)—but I might become nothing but bones if it gets any hotter and I keep sweating.

The trail began on the left side of the Missouri River at the site of Franklin, where William Becknell engineered the first trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1821. Franklin became the trail’s eastern terminus until a series of floods devastated the original town site in 1826 and 1828. The trail, which Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton had the federal government survey in 1825, crossed the Missouri between Boone’s Lick and Arrow Rock Landing (both state historic sites today), but 21st-century travelers cross on a bridge between New Franklin and Boonville. From there, it’s a series of back roads (highways 41, 65 and 24) into Independence.

Many historians believe the Santa Fe Trail bustled with wagons streaming day and night. I wonder if they had traffic jams like they have in greater Kansas City. From 1827 to 1856, this Kansas City suburb drew wagon makers, blacksmiths and outfitters who made a bundle off argonauts wanting to travel the Santa Fe, Oregon or California Trails. Since Conestoga wagons, first made in Pittsburgh, don’t have A/C and run even slower than the tourist in the Winnebago in front of me, I’ll skip on that mode of transportation.

Independence is the final resting place of Frank James (not to mention a good stop for Kansas City-style BBQ), but since 1990 Independence has also been home to the National Frontier Trails Center.

Located at 318 W. Pacific, the interpretive center houses exhibits on all three trails. The Merrill J. Mattes Research Library & Archives and the Oregon-California Trails Association also call the center home.

Independence, once known as the “Queen City of the Trails,” also features several other sites, including the 1827 Log Courthouse (107 W. Kansas). James Gang and Civil War buffs may want to check out the 1859 jail, Marshal’s Home and Museum (217 N. Main), where Frank James was held after surrendering to authorities in 1882.

Kansas City’s a good place to hang your hat for the first night on the trail, even if the Royals baseball team hasn’t been worth a darn since Dick Howser died.

It’s a great place for music, barbecue and cocktails, plus the Kansas City Public Library has a superb archives for researchers. By 1857, Kansas City had become the main eastern terminus on the trail, and ruts can be seen at 27th and Topping Avenue at the old Big Blue River Crossing as well as at Minor Park.

Kansas connections

Just southeast of Kansas City, the trail, via Interstate 35, takes us to Olathe, Kansas, and the only trail station still open to the public. On the northern rim of town sits the old Mahaffie Farmstead (1100 Kansas City Road), a two-story home built of native limestone in 1865. Travelers on the road to and from Westport took meals in the house’s basement. Today’s travelers can take tours for $3.

From now on till Dodge City, it’s Highway 56, and about a zillion sites. Where you stop is up to you. The National Park Service offers a map and guide and recommends two guidebooks: Following the Santa Fe Trail: A Guide for Modern Travelers by Marc Simmons and Hal Jackson, and The Santa Fe Trail Revisited by Gregory Franzwa.

About two miles west of Gardner, a Kansas Historical Marker notes the junction of the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails, and just east of Baldwin City, Douglas County Prairie Park preserves what travelers call the best set of wagon ruts to be found anywhere on the trail.

The next highlight is the grave of Samuel Hunt, a dragoon private during Colonel Henry Dodge’s Rocky Mountain Expedition of 1835. Private Hunt died on the return to Fort Leavenworth and is buried in the middle of nowhere, his resting place marked by a marble tombstone. It’s the oldest grave site of a soldier on the trail, and it can be found—if you’re lucky—just north of Kansas 31 about a half-mile west of the ruins of the old Havana Stage Station.

After a pit stop in Council Grove, site of the 1825 treaty with the Osage Indians that provided safe passage for the wagon trains, it’s a winding jaunt along U.S. 56 past old springs and crossings—not to mention Buffalo Bill Mathewson’s well, which slaked the thirst of many a hot mule skinner and ox, about four miles west of Lyons and a mile south on a gravel road.

Considering the hot Kansas wind, I’ll just quench my thirst with a bottle of Gatorade in my cooler and keep the A/C and stereo cranked. Besides, it’s a long haul to Dodge City. I make a quick swing around Pawnee Rock State Monument, the high landmark which served as a beacon along the trail, thinking that it certainly attracted more travelers then than today.

That can’t be said of the Santa Fe Trail Center, another certified interpretive facility two miles west of Larned, this one housing a museum, archives and library as well as a replica sod house.

Just down the road is Fort Larned, active from 1859-1878, now a National Historic Site and among the best preserved forts in the West. Allow plenty of time to tour the grounds and examine the exhibits.

If you’re ready to settle for the night, Dodge City is the likely camping spot. Although the city celebrates more of its cow town heritage than its Santa Fe Trail days, the cheesy but fun Boot Hill Museum (on Front Street) operates the site of trail ruts about nine miles west of Dodge. A short drive later you have to make a choice: Cimarron route or Mountain route?

Right or left?

The Cimarron route, shorter, faster and drier, takes you along U.S. 56 to I-25 at Springer, New Mexico. The Mountain route follows highways 50 and 350 to Trinidad, Colorado. Did I mention the Mountain route also hits Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, eight miles east of La Junta, Colorado? That makes the longer drive worthwhile.

Active from 1833-1849, the adobe post was the center of the Bent, St. Vrain and Company’s trading empire. The post has been meticulously reconstructed by the National Park Service, and the $3 admission is the best buy on the trail.

No matter the route you’re traveling, you’ll eventually pick up I-25. If time permits, drop in at the Fort Union National Monument, north of Waltrous, New Mexico. Once a sprawling army post (1851-91), Fort Union is now known for its adobe ruins and trail ruts.

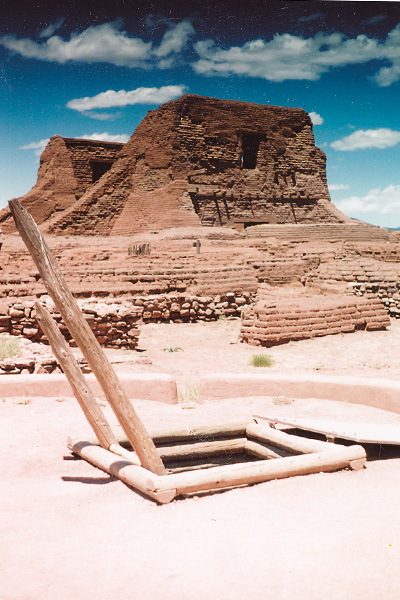

From here on, it’s smooth sailing to Santa Fe, but stop at Pecos National Historical Park before swinging into the “City Different” for green chiles, kiva fireplaces, turquoise and adobe. Indians inhabited the Pecos pueblo when the Santa Fe Trail opened but abandoned it by 1838. Nearby Glorieta was the site of the March 1862 Civil War battle that stopped the Confederate invasion of New Mexico. A building of Pigeon’s Ranch, a stagecoach station along the Santa Fe Trail and part of the battlefield, rests mere inches off Highway 50.

A marker on the Santa Fe Plaza commemorates the western terminus of the Santa Fe Trail. Cross the street and visit The Palace of the Governors Museum (105 W. Palace), which offers displays depicting New Mexico’s history and culture. Territorial Governor Charles Bent and historian Oliver La Farge are buried at the National Cemetery northwest of town.

By 1880, with the arrival of the railroad, the Santa Fe Trail had faded away. The Daughters of the American Revolution began putting up trail markers in the early 1900s, and the trail was designated a National Historic Trail on May 8, 1987.

The trail ends in Santa Fe, so now you’re free to do what brings most people to the City Different. Heck, we suspect that even William Becknell, after selling his wares in 1821 and pocketing a bunch of Mexican silver, did a little shop-ping in Santa Fe, too.

Johnny D. Boggs makes these Santa Fe Trail recommendations: BBQ turkey sandwich at Gates & Sons, Independence, MO; chuck wagon dinner at Marchel Ranch, Dodge City, KS; green chile cheeseburger at Bobcat Bite, Santa Fe, NM.