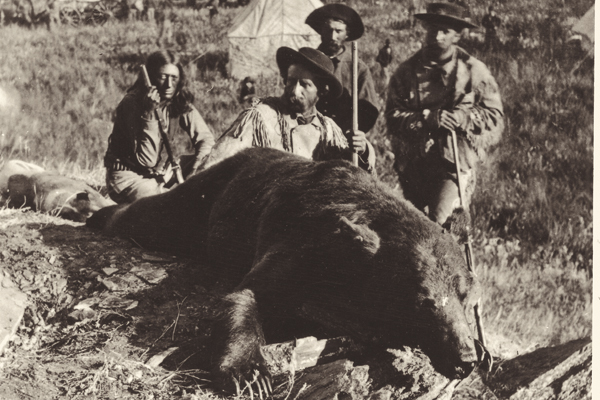

The proud slayers of a huge grizzly are memorialized in one of the most famous photographs in all of Western history.

The proud slayers of a huge grizzly are memorialized in one of the most famous photographs in all of Western history.

By August 7, 1874, when the photo was taken by William H. Illingworth, Custer had already explored the fabled Black Hills, and his dispatches, carried to Fort Laramie by scout Charley Reynolds, were full of praise for this western Eden with its “gold in paying qualities.”

Now returning eastward to Fort Lincoln, he was not far from Bear Butte when, riding ahead of his command with but three companions, he spotted a fine campsite (about two miles south of present-day Nahant, South Dakota). John Noonan and Bloody Knife then spied a huge grizzly some 75 yards distant. Custer, galloping forward, brought the bruin down with a shot from his Remington. The wounded bear turned to confront the hunters as Bloody Knife and Ludlow shot it three more times.

Custer was elated. “I have reached the hunter’s highest round of fame,” he wrote his wife Elizabeth. “I have killed my grizzly.” He ordered Noonan to haul the 600-pound behemoth back to a rock outcropping overlooking the campsite. As the wagons rolled in and the troopers set up their tents, Custer and his fellow hunters posed with their bear for Illingworth’s camera.

The intrepid pioneer photographer took two versions of this famous photograph (soon on sale throughout the East). In the first shot, the hunters are grouped around the bear, all kneeling, except for a sad-sack looking Noonan. In the second photograph, Ludlow is standing and Noonan has brushed his hat brim back to better show his face.

Within a few years, three of the men in the photograph will have met violent deaths. Ludlow survived to a ripe old age, but Custer and Bloody Knife died at Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876. Noonan was with Custer on that final campaign, but the sergeant survived as he had been left at the Yellowstone Depot in charge of the cattle herd. Death had not yet come for him.

Noonan’s celebrated wife

Having joined the Seventh in January 1872, the Fort Wayne, Indiana, native had impressed his superiors and even the colonel’s lady. “He was the handsomest soldier in his company,” noted Elizabeth Custer, “[and] we often admired the admirably fitting uniform his wife had made over, and which displayed to advantage his well-proportioned figure.”

Noonan’s wife was a celebrated lady of the Seventh, although far removed from the social circle of Mrs. Custer. Nevertheless, the colonel’s lady knew her well: “When she first came to our regiment she was married to a trooper, who, to all appearances, was good to her. My first knowledge of her was in Kentucky. She was our laundress, and when she brought the linen home, it was fluted and frilled so daintily that I considered her a treasure…. The woman was a Mexican, and like the rest of that hairy tribe she had so coarse and stubborn a beard that her chin had a blue look after shaving, in marked contrast to her swarthy face. She was tall, angular, awkward, and seemingly coarse, but I knew her to be tender hearted.”

“Old Nash,” as the laundress was called (she kept her first husband’s surname), had led a difficult life. She once even dressed as a man, driving ox teams over the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico. Her own two children had died in Mexico, but she assisted many a Seventh Cavalry child into the world as she had learned midwifery from her mother and was a skilled practitioner of that art. Often would she say, “Are you comph?” in a labored accent to the young pregnant wives. The phrase became a favorite in the regiment.

John Burkman, Custer’s orderly for nine years, recalled that no one was more “in demand to chase the rabbit when some woman was expectin’ a baby” than Old Nash. Despite her revered status in the regiment, Old Nash was unlucky in love. She was married to, and deserted by, two Seventh Cavalry troopers before meeting her third and final husband, John Noonan.

Her matrimonial trials, at least in the mind of Mrs. Custer, were the result of her industry—for her first two husbands also deserted with her substantial savings. Noonan had the best of the bargain, Elizabeth thought, “for notwithstanding his wife was no longer young, and was undeniably homely, she could cook well and spared him from eating with his company, and she was a good investment, for she earned so much by her industry.”

Her third husband was in the field on campaign when she took suddenly ill and died. She had implored those who cared for her in her final days to place her in a coffin and bury her at once. This they would not do for one so beloved by the regiment. When Old Nash passed on October 30, 1878, the ladies of the regiment carefully washed and prepared her for burial. They then made a most shocking discovery. Noted John Burkman: “We was flabbergasted.”

A dispatch from Bismarck, Dakota Territory, informed the world: “A singular development transpired at Fort Lincoln today. Mrs. Sergeant Noonan, who died last night, turns out to be a man…. There is no explanation of the unnatural union except that the supposed Mexican woman was worth $10,000 and was able to buy her husband’s silence. She has been with the 7th Cavalry nine years.”

Noonan didn’t inherit a fortune from his wife, for she gave all she had to the Bismarck Catholic Church. What Noonan did receive was unrelenting ridicule from his fellow troopers. “When Noonan come back from scout duty we told him about his wife dyin’ and all,” Burkman recalled. “He was a quiet man. He didn’t say much, but his face went white and kinda jerked. After that everywhere he went the regiment joshed him.”

Burkman was with the post carpenter on Noonan’s last day: “Noonan walked in. His face was gaunt and sorta set. The carpenter looked up. ‘Hello Noonan!’ he says. ‘Say, you and Mrs. Noonan never had no children, did you?’ We all started laughin’ and then we stopped sudden. Noonan was standin’, lookin’ at us … like an animal that’s been hurt. Then, afore we had sense to stop him he pulled out his gun and shot hisself dead, right thar at our feet.”

The newspapers reported that Noonan’s suicide had taken place on November 30, 1878, while he was alone in the cavalry stables—but the end was the same no matter the place. Back East, the Army and Navy Journal sermonized on the end of the scandal: “He crawled away lonely and forsaken and blew out the life that promised nothing but infamy and disgrace. The suicide was committed with a pistol, and Noonan shot himself through the heart. The affair created almost as intense excitement at the post as did the announcement of the death of Mrs. Noonan, but there was a sigh of relief on the corporate lips of the 7th Cavalry when its members heard that Noonan by his own hand had relieved the regiment of the odium which the man’s presence cast upon them.”

In the West, the verdict was far less judgmental. Elizabeth Custer, now a widow herself, upon reading of her beloved laundress’ death said: “Poor old thing, I hope she is ‘comph’ at last.”

Burkman and his fellow troopers, far from being relieved by Noonan’s suicide, were in fact “terrible ashamed.” He was, after all, one of them. “It takes all kinds o’ men to make up an army,” Burkman declared years later. “Officers, o’course, whose doin’s is writ up in books, but it takes a lot o’ common fellows too, like me … and Noonan—jist privates, men that don’t know nothin’ except what they’re told to do, that kills and gits killed, and that the world never hears about…. And yet to ourselves we seemed important. Noonan’s troubles meant jist as much to him as though he’d been a Major. Hundreds of graves scattered over Dakota and Montana of men that’s never been missed, never been writ up, but they was good soldiers jist the same, and without ’em thar wouldn’t’ve been no country, maybe.”

Noonan was buried in the post cemetery at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Bugler John Martini, who had carried Custer’s last message, sounded taps over the grave. Eventually reinterred at Custer Battlefield National Cemetery (Grave 573A), Noonan now fittingly rests upon the very field where so many of his comrades perished in battle. He had come, in his own way, to that same place.

Paul Hutton is a professor of history at the University of New Mexico. His book, The Custer Reader, received the John M. Carroll Literary Award from the Little Big Horn Associates.