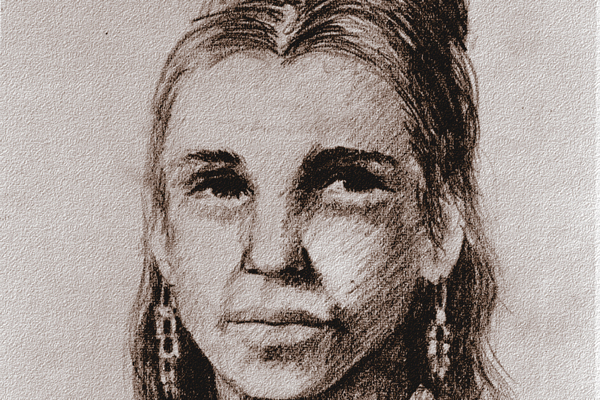

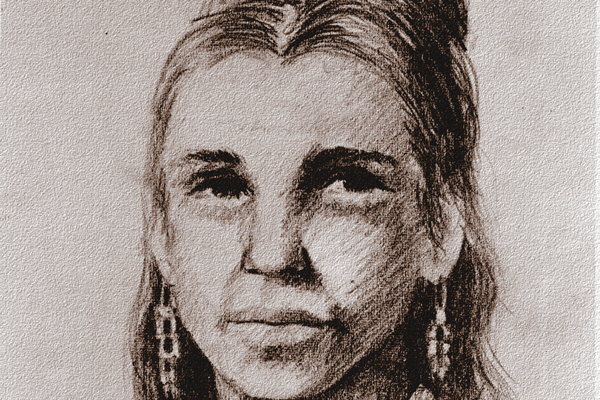

If your image of a senorita in the Old West is beautiful brown eyes shyly hidden behind a lace fan, then you’ve never heard of Juana Briones—a senorita who belied all the stereotypes and taught the American government a thing or two.

If your image of a senorita in the Old West is beautiful brown eyes shyly hidden behind a lace fan, then you’ve never heard of Juana Briones—a senorita who belied all the stereotypes and taught the American government a thing or two.

Although her name is not widely known, and her story not often told, Briones was the kind of woman who made the West what it is today—she was a businesswoman, a landowner, a healer and a founding mother of a wild land that would become California. The state’s archives note she is sometimes called “California’s Clara Barton.”

Juana was born in 1802 to a Spanish ranching and military family. Her parents and grandparents came to California in the first explosion of pioneers from New Spain, and her parents—Marcos Briones and Maria Isadora Tapia—helped build the Presidio in Mission Dolores. It was built near Yerba Buena Cove on San Francisco Bay.

By then, Juana was a teenager who’d been schooled—as much as she would ever be—by the Catholic priests who ruled the missions with an iron hand. It was then thought that a strong religious bearing was all a woman needed, and Juana was a regular at daily mass, along with other military children and the Native Americans who had been rounded up and brought to the mission for “conversion” to Catholicism.

But Juana wasn’t the type of girl to submit to that submissive atmosphere for long, as Mary Rodd Furbee notes in her Outrageous Women of the American Frontier.

As Juana became of marriageable age, her mother and father looked around the mission to find a suitable husband. The pickings were slim.

As Furbee reports, numerous criminals were among their number: “Two hundred soldiers lived in barracks surrounded by a 12-foot adobe wall. Many dressed in rags, were fond of drink and bullied the natives. One favorite pastime was hunting, shooting and branding Native American Christian converts. In fact, the padres had more problems with the Cavalry than with the supposed ‘savages.’”

Her family approved of her union to a handsome soldier named Apolinario Miranda. They were married in 1820. But what the family had expected wasn’t what it got—what it got were eight grandchildren and an abused daughter who learned how to survive and prosper.

“In addition to running their busy household, Juana supported the family economically by engaging in trade,” Furbee notes. “Because her husband had a serious drinking problem, he wasn’t much of a rancher or businessman, so Juana sold milk and beef to the crews of Russian, American and Spanish ships that docked in the bay. She also harbored sailors who jumped ship because they wanted to remain in California, ran a busy tavern and nursed the sick.”

Her skills as a midwife were used by many, and no one ever counted how many children had their broken bones set by this kind woman. She’d learned her skill with herbs from her grand-mother, who had originally learned them from native women, and she worked their magic to treat many illnesses. Oh yes, she also adopted five orphans to add to her family.

By now, Mexico was independent of Spain, and her father’s allegiances helped out this new family. As Mexico split up the large Spanish grants, they gave plots to favored families—Juana’s father got a generous land grant. He gave his daughter and her husband a piece of land outside the mission. Her husband eventually got a small grant himself. Her family originally lived on part of her father’s land but eventually moved closer to the harbor.

Juana and her husband had only the third house ever constructed in Yerba Buena, which would eventually be renamed San Francisco, according to a children’s book written about her life by Glenda Richter.

It was there that her husband’s beatings became so intolerable, she defied her family and her church, and left him. (She couldn’t actually divorce him because it was forbidden by her church.)

In 1836, she moved her family to a house near today’s Telegraph Hill, which became such a part of her family’s identity, the area came to be known as La Playa de Juana Briones.

Her husband didn’t like what was happening and tried to force her to return to his home. Juana turned to legal officials, who ordered her husband to stay away. When he didn’t, a justice of the peace seized some of his property.

Then she did something that was thought unthinkable. Because she was still legally married, her husband had access to any property she acquired. To protect herself, she turned to the only authority who could free her from this burden: the Catholic bishop.

“My husband did not earn our money. I did,” Juana told the bishop, Furbee notes. “My husband does not support the family. I do.” The bishop was so moved by her plea, knowing full well her husband was a good-for-nothing, that he granted the legal separation. Juana was free.

She went to town. Across the nation, Boston traders sought out her “California banknotes,” as they called her cowhides. She entertained lavishly, with European and American guests attending her fiestas. Her children prospered. She was a wonderment: an independent woman who was prospering on her own.

In Richter’s children’s book, The Stories of Juana Briones, she uses historical documents to imagine how Juana would have told the story of her life. One section stresses how she taught her own children the value of hard work: “Everyone had a job. The first thing my little ones learned when they could walk was how to pull weeds and load the wagon. The girls and I did the sailors’ laundry, and we mended their clothes…. My daughters Presentacion and Manuela were fine seamstresses, and they did some of the sewing. Jesus went to the boats to see what the men needed, and he delivered goods and messages for me.”

In 1848, Mexico ceded this land to the U.S. under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. Almost overnight, the sleepy little mission became a busy city, filled with all manner of men who came to get rich overnight (and ladies-of-the-night who hoped to liberate them from their gold dust).

“Juana wasn’t bothered by the U.S. coup at all,” Furbee states. “In fact, when her Anglo friends suggested she become an American citizen, she did.” But she also found life in the teeming city too frantic, and with the money she’d made, she bought a 4,000-acre ranch in Santa Clara Valley and named it Rancho La Purisima Conception.

“The Briones family ranch was a home, social hall, and hospital all rolled into one,” Furbee notes. “Anglo, Hispanics, and Native Americans came for bear fights, calf roping, and pig roasts. The place teemed with a dozen dogs and children of all sizes, ages, and races. Sick people also came to recuperate under Juana’s watchful gaze.”

But the peaceful coexistence didn’t last. When the U.S. made California a state in 1850, it demanded that the original landowners prove they had title to their property. Many were cheated out of their lands. Juana faced yet an additional problem: in 1852, the U.S. Government informed her it intended to seize her land around the Presidio that had originally been granted in her husband’s name. Her husband was dead by then, and the government said she had no legal right to the property.

She wasn’t about to take this without a fight—it would end up being a 12-year battle that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. She won, and her right to the land was upheld. Along the way, many of the Anglos she’d helped over the years came to her side to fight for her rights. Today, this land is near the corner of Lyon and Green Streets just outside the Presidio. Juana’s beloved ranch is now Palo Alto, California.

By the time she died in 1889, she was a California legend. And to this day, she stands as a role model for strong women.