When I finally announced that I was going to become a doctor it broke the heart of all my friends and I was publicly disgraced. Women that I had known for years drew their skirts aside and went by on the other side of the street; men refused to bow to me, and friendless and alone, I started by stage for San Francisco on my way to Philadelphia.”

When I finally announced that I was going to become a doctor it broke the heart of all my friends and I was publicly disgraced. Women that I had known for years drew their skirts aside and went by on the other side of the street; men refused to bow to me, and friendless and alone, I started by stage for San Francisco on my way to Philadelphia.”

Bethenia Owens-Adair’s life was filled with controversy—some of it admirable, some of it questionable.

She dared buck the norms of her day as a female doctor in the West, but she also was a national leader in the despicable sterilization movement that swept the nation in the early 1900s.

Her life story shows a woman who definitely knew her mind and was hellbent-on-leather to do it her own way.

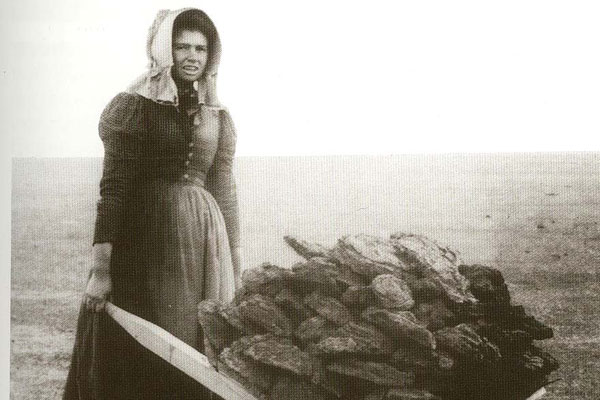

Bethenia Owens was born February 7, 1840, in Missouri, but her family soon joined the migration west to Oregon. She never attended any school until she was 12, and then only for a summer, for at 14, unable to read or write, she married one of her father’s farmhands. Legrand Hill wasn’t much of a provider and instead of building a home and creating a farm, he preferred to go off hunting and fishing. His bride put up with it for four years, but she divorced him when she was 18, leaving with her toddler to rejoin her family. Besides her son George, she wanted nothing to remind her of Mr. Hill and restored her maiden name.

She finally attended school to get a basic education, while working to support herself and her son. In 1867, she opened a millinery in Roseburg, Oregon, and over the next six years, she made it a success.

But she wasn’t content. She’s quoted as admitting: “The regret of my life up to the age of thirty-five was that I had not been born a boy, for I realized very early in life that a girl was hampered and hemmed in on all sides simply by the accident of sex.”

The suffrage movement helped propel her—she coordinated a visit to Oregon by Susan B. Anthony in 1871—and she shocked everyone by announcing she wanted to attend a medical school in the East. “I can assure you it was no laughing matter then to break through the customs, prejudices and established rules,” she once said.

She left her son with her friend Abigail Scott Duniway, editor of the suffragist journal New Northwest, and enrolled at the Eclectic Medical College in Philadelphia. In 1874, she completed her course of study.

She returned to Oregon and set up a medical practice, but not before so scandalizing the community, she feared being tarred and feathered.

“On her return to Roseburg those male doctors who opposed women in the profession pointedly invited her to attend an autopsy on a male corpse,” wrote Dorothy Gray in Women of the West. “The doctors and many of the townspeople were shocked when she accepted the invitation. ‘Don’t you know that the autopsy is on the genital organs,’ one of the doctors said. ‘No,’ said Bethenia as she stepped forward to participate, ‘but one part of the human body should be as sacred to the physician as another.’”

The public condemnation so enraged her that she moved to Portland and became a “bath doctor,” a medical style she’d learned in Pennsylvania that treated patients with electrical and medical baths. Her practice was so successful, she sent her son to medical school and a sister to college. She also adopted the daughter of a deceased patient.

At 38, she treated herself by enrolling in the University of Michigan Medical School, one of the few universities that then admitted women in any field. She got her M.D. in 1880. After a tour of European medical facilities, she returned to Portland and specialized in eye and ear diseases. Gray notes she soon was earning the huge sum of $7,000 a year, but she had few male patients. There was satisfaction, though, in counting as patients some of the Roseburg women who had once told her they’d never have a female doctor.

In 1884, she married a childhood friend, Col. John Adair, and they moved to a farm. They adopted two children: Bethenia’s grandson (George’s wife had died) and the newborn baby of a patient. Bethenia gave birth to a girl at age 47, but the child lived only a few days.

Bethenia spent many happy years active in the Oregon State Medical Society and the women’s suffrage movement—but she wasn’t yet done with controversy.

It may seem strange that a female suffragette doctor would lead the “eugenics” (or “good breeding”) movement, but that’s what happened. In 1883, Dr. Owens-Adair visited the state insane asylum, leaving with the vow to dedicate her “pen and brain to preventing disease and crime through propagation.”

She wrote that “sterilization is the simplest, the purest and the greatest remedy that has ever been discovered by man…. At no distant day we shall have a federal law. Then we shall begin the propagation of supermen and women, not pygmies.”

Her cause was championed by The Oregonian newspaper, which declared, “We breed criminals in this country and will probably continue to do so until Mrs. Dr. Owens-Adair succeeds in getting her sterilization law on the books.”

She wasn’t alone in thinking it was proper to sterilize anyone considered “undesirable” or “manifestly unfit from continuing their kind,” including “all feebleminded, insane, epileptics, habitual criminals, moral degenerates and sexual perverts who are a menace to society.” Eugenics was also championed by social reformers such as Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood; author H.G. Wells; and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Bethenia introduced her first eugenics bill in the Oregon Legislature in 1907, but it wouldn’t actually become a state law until 1917. Oregon joined 32 other states that eventually forced sterilization on nearly 64,000 American citizens. It is said Hitler used the U.S. laws to justify Germany’s sterilization program that began in 1933 and resulted in more than 350,000 being denied their right to reproduce.

California would sterilize the most, some 20,000, with Virginia (7,400) and North Carolina (nearly 6,300) coming in second and third. Those targeted often reflected social prejudices. As Newsweek magazine recently reported, North Carolina focused on blacks and “some women were sterilized for being seen as lazy or promiscuous.” Oregon sterilized about 2,300 and was known to particularly target homosexuals. Its eugenics law endured far longer than most states, which started abandoning the practice in the 1970s; Oregon’s law stayed on the books until 1983.

Some states have started apologizing—Virginia in 2001, Oregon in 2002, while others, such as North Carolina, are considering reparations to those robbed of the chance to be parents. There is no evidence that Dr. Owens-Adair ever had second thoughts about her push for this vile approach to social engineering, but most everyone else has. Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber, acknowledging a “great wrong,” said in his apology, “To those who suffered, I say, ‘The people of Oregon are sorry. Our hearts are heavy for the pain you endured.’”

How would Dr. Owens-Adair feel to know that every December 10, Oregon marks Human Rights Day in honor of all those sterilized? The day affirms “our commitment to the value of every human being in Oregon,” the proclamation states.

Dr. Owens-Adair stayed active in medical and community events until her death in 1926 at age 86. She best expressed the joy of her life in 1905 when the American Medical Association honored women physicians. “This is the first time in the history of the sessions of the A.M.A. that women have had a distinct recognition,” she happily noted. “It is another instance of the West setting the pace and establishing precedents for the rest of the country to follow.”