I have spent years traveling overland trails in the West; some might say I have an obsession for traveling three miles an hour in a covered wagon.

I have spent years traveling overland trails in the West; some might say I have an obsession for traveling three miles an hour in a covered wagon.

During the past 20 years I have been able to follow the routes to Oregon and California, and the Mormon Pioneer Trail in Utah. I have traveled the Bridger and Bozeman Trails to the gold fields in Montana. And I have been on the Cherokee and Overland Trails in southern Wyoming. While walking or riding in a wagon along our pioneer trails, I have seen some incredible vistas.

Sadly, every year we lose more of these trails to the ravages of both nature and man. Erosion scours ruts, wind-blown dust fills trail swales and farmers plow segments. Homes and barns go up just feet from the trails—sometimes right over the top of the historic ruts. Energy development and industrial activities cause their own impacts, if not to the actual trails, then often to the visual landscapes.

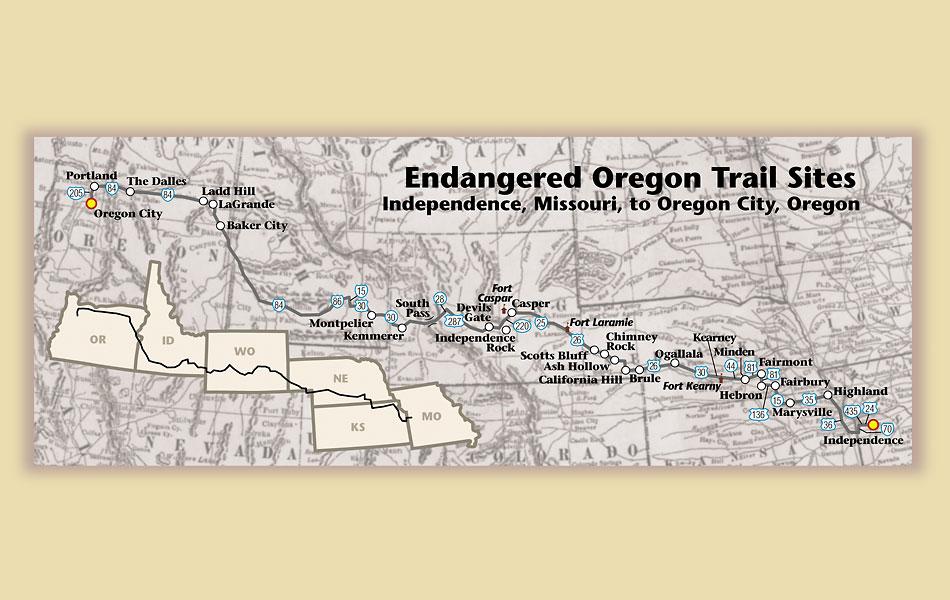

Last year the Oregon-California Trails Association (OCTA) attempted to identify the Top 10 Endangered Sites on the Oregon Trail. It wasn’t able to do it, in part because members couldn’t agree on which places should “qualify” for such a list. I know from my own travels along these trails that important sites have already been or are in imminent danger of being permanently changed.

In 1993 I traveled with the Oregon Trail Sesquicentennial Wagon Train led by Morris Carter of Casper, Wyoming. His four teenaged daughters, Oneta, Ivy, Ariane and Katrina, along with Ben Kern, also of Casper, and Earl Leggett, of Aurora, Oregon, drove wagons from Independence, Missouri, to Independence, Oregon.

On July 23, 1993, I rode with Kern from Pacific Springs to Parting of the Ways in Wyoming. Of that journey, I wrote, “We had a view of sage, bitterbrush and four remarkable sets of parallel ruts. The landscape had changed little during the past 150 years.… We could have easily believed we’d time-traveled. We saw no vehicles, no power lines, no roads, no other people, and because of the clouds, not even any jet contrails.… West of South Pass this land hasn’t changed much since the Great Migration.”

Kern and I later wrote a book about that journey, Wagon Wheels: A Contemporary Journey on the Oregon Trail. Best-selling novelist Kathleen O’Neal Gear, who had connections with the trail through her earlier work as a Wyoming State Historian for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, wrote the foreword.

“It is a great national tragedy that many people in modern America cannot even imagine a place where a man or woman can stand and gaze into infinity, without fences, telephone poles, or houses to mar the view. Or imagine why it matters,” she wrote. “If nothing else, readers will see that the western experience is, and always has been, a thing of the land, that hardship is the price of freedom, and its exceedingly great reward.”

Travel with me now as I take you to some of the special places that I believe are truly endangered along the Oregon Trail. Trail people across the land will no doubt disagree with my choices. You may write letters to this publication or to other sources telling me how wrong-headed I am. Good. Please do! If I make you think about these historic places—and perhaps even criticize my choices—then I have succeeded in my effort to preserve them, because I have engaged you in the work of caring for our Western lands.

#1 South Pass

I believe my #1 Oregon Trail site—South Pass—will not be disputed by anyone. This pass through the Rocky Mountains is the reason the Oregon, Mormon, California and Pony Express Trails went through central Wyoming. During the period of emigration, from 1841 to 1869, somewhere around half a million folks crossed through here. Of course, Indians and even mountain men and explorers used this pass long before the first pioneers.

Wyoming Highway 28 now bisects the pass not far from the pioneer trails. Recent studies by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service and OCTA have shown that the routes of the early travelers are widely spaced through the pass. Efforts are underway to define South Pass. Some contend it starts down in the Sweetwater Valley, dozens of miles east of the actual point where the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans divide, and then continues beyond the divide itself for several miles.

Risks to the trail in this area are diverse. Gold mining activity that began as early as the 1860s, and which continues to this day, is one. Recurring suggestions that an oil or gas pipeline could cross the pass, or that wind energy developments could be put in place in the area, are greeted with fear and trepidation by OCTA and other groups, such as the Alliance for Historic Wyoming. The Bureau of Land Management is completing a management plan for the area that takes into account these potential uses for South Pass.

It is easy to rail against “big industry.” It is more difficult to address an issue that is prevalent in this area of the Oregon Trail—overuse, which leads right to my second site.

#2 Rocky Ridge

Travelers to Oregon and California drove their wagons up the east side of South Pass and for the most part avoided Rocky Ridge. But the shelf rock that gives the incline its name became a tremendous obstacle to travelers on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, particularly the men, women and children who took their possessions to Utah by using handcarts. The hardships of the James Grey Willie Handcart Company in 1856 are well known, as those English travelers struggled up Rocky Ridge in mid-October, freezing their hands and feet in making the crossing.

Hundreds of modern-day pioneers re-create this journey each summer, pushing and pulling their own handcarts from 6th Crossing to Willow Creek. Some say the current users are literally loving the trail to death. In order to make their own journeys easier, they have moved rocks and “improved” the trail, in the process changing it forever.

#3 Ladd Hill

Wind turbine development is widespread in Oregon, so as to provide “green” energy to an ever-growing population. Unfortunately for the Oregon Trail, many of the places best suited to wind power production are along the trail. Already hundreds of wind turbines spin across Oregon, generating energy and consternation. While some developers make efforts to avoid the trail, by locating turbines away from actual ruts, the reality is that turbines are highly visible for miles, as they are often placed on ridge tops.

The OCTA is monitoring several Oregon wind power projects. In many cases the group attempts to work with developers to reduce impacts. One that has garnered significant attention is the Antelope Wind Power Project in the Ladd Hill area of eastern Oregon near LaGrande. Voters opposed the wind project in the fall 2010 election. But the project is on private property; in all likelihood, it will be developed at least to some degree in the future.

#4 Sublette Cutoff and Lander Road

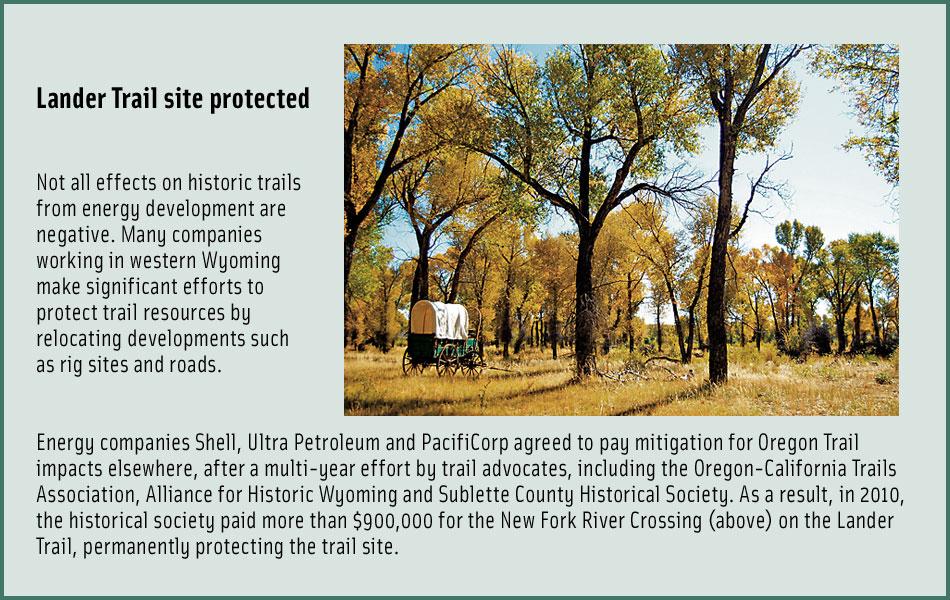

I am grouping these two routes west of South Pass because the impacts that affect them are common and already present. Our nation needs energy, and western Wyoming is one of the greatest onshore resources available for both oil and gas. In the two decades since I first rode a wagon across this landscape, hundreds of oil wells have been drilled, miles of roads to serve those oil and gas fields now crisscross much of the land and development in the Jonah Field near Pinedale, Wyoming, has perhaps irretrievably affected air quality along the route

of the Lander Road. That route was the first government-engineered road in Wyoming, constructed in 1857

by a team organized and led by Frederick Lander.

#5 Iowa and Sac & Fox Mission and Trail Ruts

Budget cuts have caused the closing of the Kansas State Historical Society’s Iowa and Sac & Fox Mission, near Highland, Kansas. The state historic site not only provided information about those eastern tribes and their connections to the land and the trails, but also shared some remarkable Oregon Trail swales. Although visitors can still see the site and the trail remnants, the closing of the museum means little interpretation for visitors. The exhibits have been relocated to the Shawnee Indian Mission in Fairway.

#6 Chimney Rock

Chimney Rock, the most recognized landmark on the trail in Nebraska, has been protected for generations by private landowners who control the rangeland around the sentinel rock.But the 551 acres of land near Bayard is at risk from potential residential or commercial development.

The land in Bayard near Chimney Rock is owned by Gordon and Patty Howard. They operated the Oregon Trail Wagon Train cookout and living history business in the shadow of the landmark for nearly three decades. They purchased the land themselves to keep it from development. As Gordon himself has said, “We bought it to preserve it. This is sacred ground to the expansion of the country.”

To purchase the Howards’s land, Nebraska State Historical Society asked Nebraska schoolchildren to contribute Nebraska state quarters that have the image of Chimney Rock on them. The initiative was marginally successful, with about a third of the more than $1 million purchase price raised.

The state already owns 80 acres that form the Chimney Rock National Historic Site and eight acres at a nearby visitor center. The parcel the Howards own would provide a square-mile prairie grass buffer at the site. Efforts are now underway to establish a conservation easement for that ground, ensuring that it will remain as pasture and in agricultural use far into the future. Even an easement costs money, though, so those Nebraska quarters are still being collected.

#7 End of the Oregon Trail Center

Not all endangered sites are on the trail itself. The ongoing economic crisis has also significantly affected those who interpret the trail. In Oregon, reduced funding led to the closing of the End of the Oregon Trail Center in Oregon City.

While OCTA sponsored a benefit that showed its documentary film, In Pursuit of a Dream, to raise funds for the center, it remains closed. Not everyone can take the time or has the resources to actually follow historic trails like the Oregon Trail, making such trail centers vital to the work of informing people about the trails.

Other visitor centers and museums impacted by similar budget cuts include those in Ash Hollow, Nebraska, and the Iowa and Sac & Fox Mission in Kansas (see #5).

#8 Pipelines and Transmission Lines across Idaho and Wyoming

Plans for wind power projects in Oregon, Idaho and Wyoming, and for ongoing oil and gas development in Wyoming, place Idaho trail sites at risk from development of new pipelines and transmission lines. The proposed Ruby Pipeline would cross Idaho from Wyoming to Oregon, while the Gateway West Transmission line that is planned to link Glenrock, Wyoming, and Murphy, Idaho, has potential for significant impact to Oregon Trail sites.

#9 Scotts Bluff, Fort Mitchell, Robidoux Pass and Horse Creek Treaty Site

These sites offer not so much an endangerment but rather a potential for opportunity.

Effort is underway to establish a National Historic Park that would involve the future management of Scotts Bluff National Monument, the site of Fort Mitchell, Robidoux Pass and the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty Site, along with Chimney Rock (see #6).

Currently Scotts Bluff is facing no serious impacts and Robidoux Pass is also protected by private landowners. The Fort Mitchell site, also privately owned, is now a field, but an archaeological survey has located the historic fort location and remains (deep in the soil). The risk to the site comes from recurring suggestions that a railroad overpass and other highway work might occur close to the location.

Should the National Historic Park concept, which is now being championed by Heritage Nebraska, move forward, it would help ensure the integrity of all these sites.

#10 Sweetwater Valley

What makes the Sweetwater Valley—from Independence Rock to South Pass—my favorite place on the entire 2,000-mile trail to Oregon is its open space. People do live here, including ranchers and the residents of Jeffrey City and Sweetwater Station, but, in part because of its isolation, the Sweetwater Valley is little changed from trail days. If you know where to look, you will see the ruts of the Oregon Trail. And this area is prime for awe-inspiring views of Independence Rock, Devils Gate and Split Rock.

Potential dangers to this setting and the Oregon Trail resources located here lie in the possibility of renewed uranium development, oil and gas pipelines (see #8) and wind power projects that could place large turbines through the valley. Although nothing is imminent, this is an area that has been eyed by development companies and thus bears watching.

It is not enough to write about the overland trails, nor even to travel them as the pioneers did. Let’s work together to protect and preserve the Oregon Trail and, in doing so, truly honor those pioneers whose dreams paved the way for all of ours.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

Old West meets New West as a wagon train travels near the FMC plant in southwestern Wyoming. In this particular area, the Oregon Trail is farther to the south and you cannot see the industrial plant from the actual trail.

– All photos by Candy Moulton –