Today, Pistol Pete, his six-shooters popping the air, is the iconic symbol for three Western universities: Oklahoma State University, the University of Wyoming and New Mexico State University.

Today, Pistol Pete, his six-shooters popping the air, is the iconic symbol for three Western universities: Oklahoma State University, the University of Wyoming and New Mexico State University.

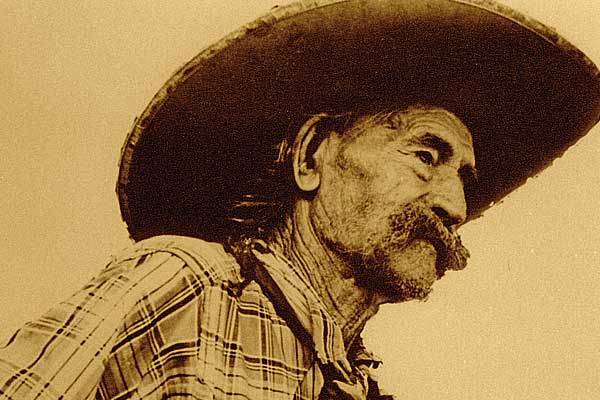

But on the American frontier, the real-life Pistol Pete, named Frank Eaton, became known for his speed with his six-guns.

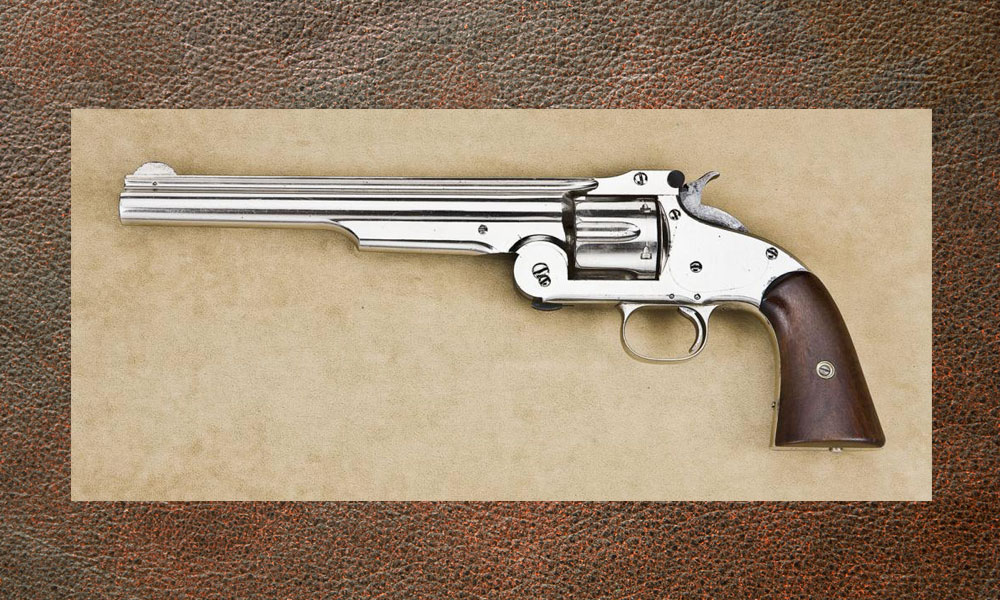

He was eight when the bottom fell out of his world. Union and Confederate riders were still struggling for control of Kansas, though the Civil War had ended. One night, six riders from the Campsey and Ferber families called his pro-Union father outside and shot him down. After the funeral, neighbor Mose Beaman gave Eaton a pistol. The boy vowed to hunt down the six.

Eaton’s story could have gone the way of a typical vengeance killing, except for an odd twist. With his mother remarried, he ended up in the Cherokee Nation, where whites were a minority and the law was the Cherokee Lighthorsemen.

Young Cherokees proved themselves with weekend shooting contests and horse races, and Eaton joined in, earning a reputation before he was 15. When he journeyed to Fort Gibson to improve his shooting skills, he beat the soldiers in every contest, causing the commanding officer to dub him Pistol Pete.

His shooting prowess proved useful when the Cherokees informed Eaton that some of the outlaws stealing their cattle and horses included the Campseys and Ferbers. Eaton shot it out with Doc Ferber and another man, killing them both.

By age 17, Eaton was riding with famed Cherokee Police Capt. Sam Sixkiller, who was also a deputy U.S. marshal. Eaton claimed Sixkiller helped make him one of the youngest deputy U.S. marshals serving in “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker’s court. Official records have him working for Judge Parker, but his status is marked unclear. “When I rode for Parker for the six to eight years, some 65 officers were killed,” Eaton wrote in his autobiography. That included Sixkiller, who was murdered on Christmas Eve 1886.

Eaton drifted into cattle detective work. When he was ordered to Texas to catch rustlers, he remembers his girlfriend Jennie giving him a crucifix to wear. During a shoot-out with some rustlers—the Texans had decided not to take any alive—Eaton got shot in the chest. Jennie’s cross apparently stopped the bullet. Riding back to ask her to marry him, Eaton discovered she had died from pneumonia.

In the 1880s, when word reached Eaton that Wyley Campsey was operating a saloon in Albuquerque, New Mexico Territory, Eaton walked in and challenged Campsey and his two gunmen. After the smoke cleared, only Eaton survived.

His account does have a hole in it. He states Pat Garrett hid him after the gunfight, yet the sheriff didn’t live in Albuquerque until the turn of the 20th century. Eaton, who was in his 80s when he wrote his autobiography, might have thrown that in to liven up his story.

During the 1889 Oklahoma Land Run, Eaton staked out a farm southwest of Perkins, where he was first the town sheriff and then the blacksmith. He married twice and raised nine children before he died in 1958 at age 97.

His legacy became a part of sports history about 30 years before his death. In 1923, he rode his horse in the Armistice Day Parade just as students of Oklahoma A&M, Oklahoma State University’s predecessor, were searching for a new school mascot. Taken aback by Pistol Pete, they began putting his image on shirts, book covers and school banners. Iowa’s Collegiate Emblems, which handled school supplies, began flashing the image of Pistol Pete at all Western colleges, and Frank Eaton—Pistol Pete—became immortalized.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details to editor@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos.