Before the Oregon Trail, before the cattle drives, before Wild Bill Hickok and Wyatt Earp, fur trappers—mountain men—opened the West.

Before the Oregon Trail, before the cattle drives, before Wild Bill Hickok and Wyatt Earp, fur trappers—mountain men—opened the West.

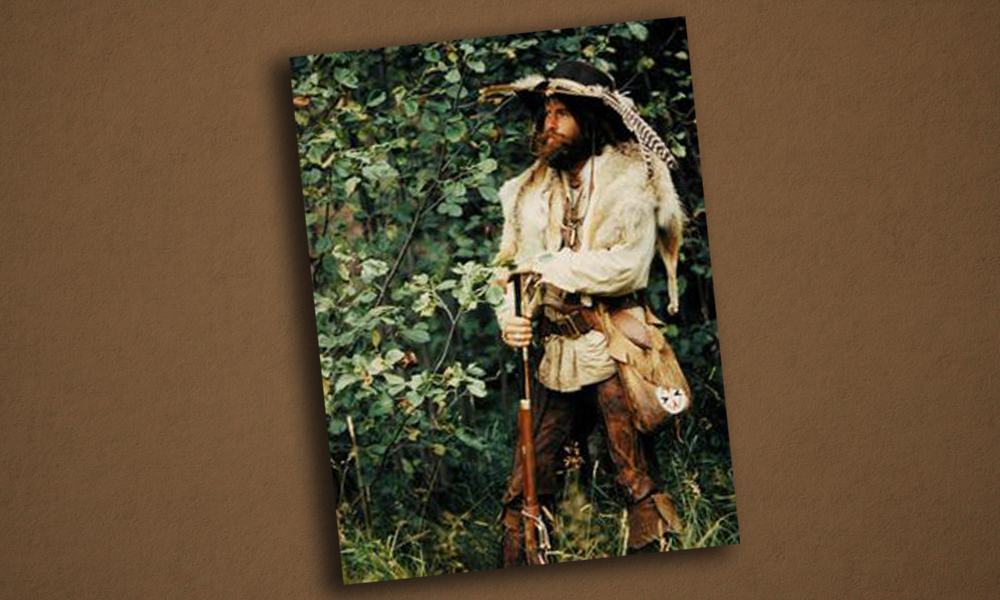

In their heyday they numbered but a few hundred, yet these intrepid frontiersmen penetrated a land known only to the Indians and within 20 years paved the way for all who would follow.

The economic engine that drew men such as Jedediah Smith and Jim Clyman was the beaver, with its fine, barbed underhair that hatters pressed into felt and then molded into hats. Beaver pelts—“fury bank notes” as they were sometimes called—could make a man rich. All he had to do was journey into the unknown, freeze his legs in icy streams while setting his traps and risk losing his scalp to Indians or grizzly bears.

The vanguard of the mountain man era included many members of Ashley & Henry, the fur trapping partnership of William Ashley and Andrew Henry, which was a forerunner of the famous Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Some, like Clyman, were seasoned trappers; many others were simply out-of-work youngsters who entered the business by answering newspaper ads seeking “enterprizing young men” to ascend the Missouri River. Amazingly, the ads attracted many who’d leave their marks in the annals of the fur trade: Tom Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Bill Sublette, David Jackson, and the crème de la crème, Jedediah Smith, who would become not only one of the most famous mountain men but also one of America’s foremost explorers.

During his first year on the upper Missouri in 1822, Smith showed his mettle and it probably surprised no one when Ashley chose him as partisan (commander) of his own trapping brigade.

In 1823, the Arikaras closed the Missouri to river traffic (see True West January 2002, p. 36), which compelled Ashley to send his brigades overland from Fort Kiowa, a trading post belonging to Berthold, Chouteau & Pratte (a.k.a. the French Company) that was located about 25 miles above the mouth of the White River (near Chamberlain, South Dakota).

In late September, Smith’s 12-man brigade headed west, following the White. The men walked, since their horses were needed to pack their supplies. Leaving the White, they crossed to the southern edge of the Black Hills, and then dropped into the Powder River basin. Hoping to winter among the Crow Indians, Smith dispatched Edward Rose, a seasoned trapper of mixed parentage, to find their camp.

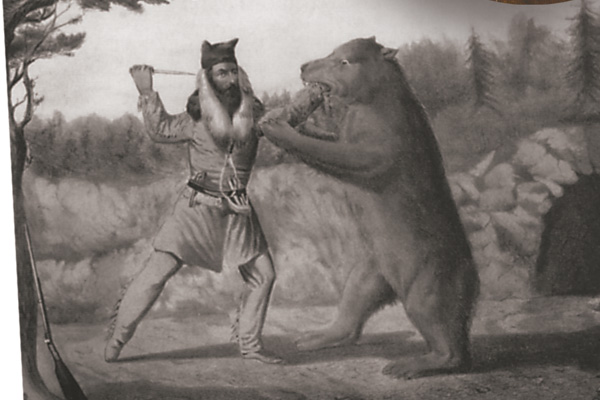

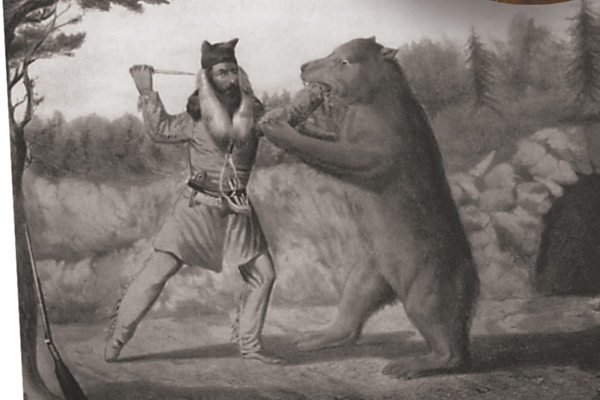

Five days later, the brigade was moving single file through a brushy bottom when it surprised a giant grizzly, which attacked Smith, nearly ripping off his scalp. Before the other trappers could kill the bear, it disappeared into the brush. Using a needle and thread, Clyman stitched the partisan back together (see above sidebar for Clyman’s firsthand account).

After Clyman finished his needlework on Smith’s head, the partisan mounted his horse and rode about a mile to a small stream where the men made camp. Never one to abide sitting around, Smith allowed himself only 10 days to heal before insisting the brigade move lest it be caught by the coming winter. For the remainder of his short life (he was killed by Comanches on the Santa Fe Trail in 1831), Smith wore his hair long to cover his scars.

The Crows welcomed Smith’s brigade to their camp, set in a protected valley off Wyoming’s Wind River (probably near Dubois). The Indians’ hospitality was also shared by another Ashley brigade, which was commanded by John Weber, a former Danish sea captain.

By February 1824, Smith was itching to leave. Outfitted with horses from the Crows, he and his brigade headed west toward the Continental Divide. Heavy snow soon stopped their progress below Union Pass in the Wind River Mountains, forcing a retreat to the Crows’ camp. After the trappers returned, the Crows told Smith about another pass a bit south of where he had failed. Although this time Smith’s men nearly starved from a lack of game, they succeeded in crossing the Continental Divide on a grade that would eventually prove gentle enough for wagons and play a critical role in America’s Westward expansion—South Pass. Others had used South Pass before Smith, but historians credit him for making it known to the public.

West of the Wind River Mountains, in the valley of the Seeds-kee-dee (now known as the Green River), the trappers found a beaver paradise. Smith split his brigade into two groups for trapping, taking command of one and putting the other under Tom Fitzpatrick. The parties agreed to rejoin just east of South Pass on the upper Sweetwater River in mid-June.

After harvesting numerous beaver pelts, Fitzpatrick, Clyman and the rest of their company reached the rendezvous site ahead of Smith’s. Wanting to send their furs back to St. Louis via boat rather than pack horses, Fitzpatrick and Clyman rode down the Sweetwater about 15 miles to see if the river was navigable. Telling Clyman to scout farther downstream and wait, Fitzpatrick returned to the main camp. By now, Smith’s brigade had arrived. Leaving Fitzpatrick in charge of making a bull boat (buffalo hides stretched over a willow frame), Smith rode east to fetch Clyman. Reaching the confluence of the Sweetwater and North Platte Rivers, the partisan found Clyman’s camp, but no sign of the trapper, merely fresh tracks from a large Indian war party. Figuring that Clyman’s scalp was now decorating some warrior’s lodgepole, Smith turned back up the Sweetwater to deliver the bad news.

By now snowmelt in the Wind River Mountains was increasing the Sweetwater’s flow by the hour. Taking along two helpers, Fitzpatrick launched the bull boat and its load of pelts, allowing Smith and the rest of the brigade to continue trapping. Fitzpatrick’s instructions were to deliver the furs to William Ashley and then lead him back to the mountains with supplies. The plan called for Ashley’s pack train to rendezvous the following summer with the brigades of Smith and John Weber (plus Ashley’s other trappers who were operating around the mouth of the Bighorn River in central Montana) on the Green River or one of its tributaries.

The scheme nearly fell apart when Fitzpatrick’s bull boat sank either at a treacherous rapid on the Sweetwater called Devil’s Gate or (more likely) in the upper North Platte River. Fitzpatrick and his companions lost two of their rifles and all of their ammunition, but did manage to salvage most of the furs. Unable to kill more buffalo to make another boat, they dug a hole and cached the furs and then started walking toward the Missouri River.

Hungry, but no worse for wear, Fitzpatrick and his two men eventually reached the U.S. Army’s Fort Atkinson (north of Omaha, Nebraska). Imagine their shock at seeing Jim Clyman, who had arrived just 10 days earlier.

Clyman had slipped away from the Indian war party that Smith assumed had killed him. Figuring the Indians had wiped out the brigade, Clyman had headed east on foot, following the North Platte toward the Missouri River and safety. He had no way of knowing that Fitzpatrick would soon follow in his footsteps.

Happy to know Clyman was still alive, Fitzpatrick penned a letter with Jedediah Smith’s instructions to William Ashley in St. Louis, asking Ashley to meet him at Fort Atkinson with supplies for the brigades that were still in the mountains. Fitzpatrick then borrowed horses and he and the other trappers headed back to retrieve the cached furs.