While Seraphim Falls has all the trappings of a traditional Western, at heart, it’s a metaphoric chase picture, more Les Miserables than Last Train to Gun Hill.

While Seraphim Falls has all the trappings of a traditional Western, at heart, it’s a metaphoric chase picture, more Les Miserables than Last Train to Gun Hill.

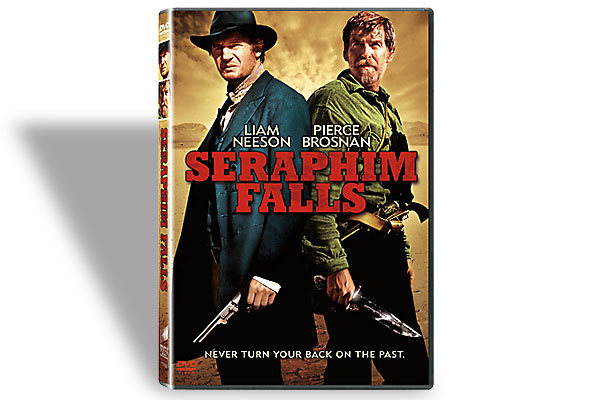

Set in 1868, the film follows Gideon (Pierce Brosnan) and Carver (Liam Neeson), from the high winter pines (Oregon and New Mexico doubling for Nevada’s Ruby Mountains) to the parched desert (New Mexico again, possibly doubling for Death Valley).

Gideon, the pursued, seems to be getting the worst of it when we meet him. Barefoot, freezing—determined to survive, Gideon is nothing if not resourceful, digging out bullets, cauterizing his wounds with a hot Bowie blade and leaping off impossible waterfalls into icy rivers. He’s tenacious and impossibly tough, although he does manage to get his money stolen by a sneaky whelp.

Carver, the pursuer, is warmly dressed and on horseback, as are his hired goons. Carver appears to be the bad guy, but over time, we learn that Carver is seeking revenge for something Gideon was responsible for near the end of the Civil War. Funny, then, that we continue to side with Gideon even when the ugly truth is revealed. Gideon is the more sympathetic of the two because he just wants to be left alone with his ravenous guilt, while Carver comes off as a bully and an ineffective wimp.

It’s revenge and retribution set against classic Western elements such as Asian railway workers and bible thumpers in covered wagons—but it’s all curiously skewed, like one of those cartoons where Elmer and Bugs are frantically running while the scenery behind them keeps changing. The chase is the thing. In some ways, the movie echoes Ridley Scott’s The Duellists as the two characters in that film (played by Keith Carradine and Harvey Keitel) also engage in a series of confrontations over a spate of time.

The actors give a fine performance and the cinematography by John Toll (Braveheart; The Thin Red Line) is outstanding, but in the final analysis, Seraphim Falls takes the traditional revenge Western, adds some last-minute surrealistic flourishes, stuffs it all through an existential sausage grinder and winds up at the end as little more than fleeing and nothingness.

The DVD contains a 20-minute making of feature and a commentary track with Brosnan, director David Van Ancken and production designer Michael Hannen, which noodles about but does offer some insight into the background of the picture. Too bad that the “dwarf and hooker” scene that was cut from the film wasn’t included as an extra, since they describe it during the commentary. Apparently, it had test audiences in stitches.