The Old West frontier town was dirty, dusty, smelly and often dangerously unhealthy.

The Old West frontier town was dirty, dusty, smelly and often dangerously unhealthy.

In those early days most people did not understand or appreciate certain sanitary notions that are taken for granted today. These axioms of public health (often ignored, even today) range from covering one’s mouth when coughing or sneezing, washing one’s hands after going to the bathroom (or outhouse), keeping flies away from food, not sharing a common drinking cup or wash towel and, my favorite, not spitting on the sidewalk.

Whether taking careful aim at a barroom spittoon or “letting loose” onto boardwalk planks, sick, TB consumptive or, more commonly, tobacco-chewing adult males sometimes spread filth into their environment, often without a second glance from those near the line of fire. Although perhaps grossly offended by such behavior, most adults simply did not understand the potential lethality of being targeted by the infectious aerosol or splatter.

The danger of flies (with resulting maggots) was more commonly linked to food spoilage than to food contamination. The latter was often caused by toxic E. coli bacteria, riding on the flies’ feet, embedded within tiny amounts of cow dung from a nearby corral.

The most modern frontier hotels at the close of the 19th century may have had a “water closet” or indoor bathroom, usually shared by all patrons staying in rooms on the same floor. These customers also shared each others’ germs by using a common towel and drinking ladle supplied “at no extra charge” by the hotel proprietor.

Frontier docs usually confined themselves to the straightforward surgical treatment of injuries and the therapeutic and supportive treatment of diseases. Relatively few stepped upon the soapbox of public health issues and disease prevention.

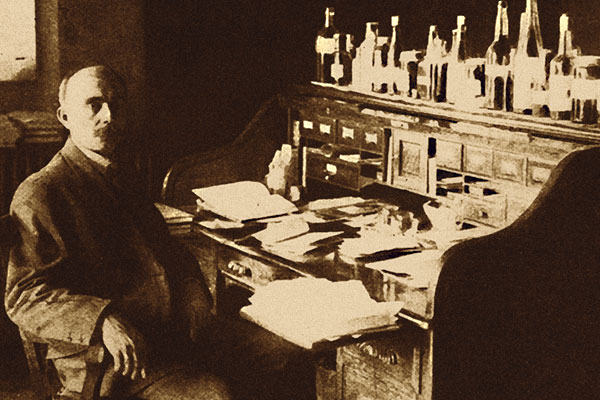

One extraordinary exception to this trend was a pioneer Kansas physician and eventual public health icon, Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine. Born on September 17, 1862, in Emlenton, Pennsylvania, Dr. Crumbine practiced in Dodge City, Kansas, beginning in 1889, shortly after he graduated from the Cincinnati College of Medicine and Surgery. He was appointed to the State Board of Health in 1899. A strong proponent of public health regulations, he left his clinical practice in 1907 to pursue a full-time public health career.

The Kansas Historical Society noted that he began his public health crusade by “attacking the use of ‘common’ drinking cups and soon had abolished their use on railroads and in public buildings.” He criticized the use of “roller” or continuous towels often used in public places. He focused upon efforts to halt the spread of disease by inventing the slogans “Don’t Spit on the Sidewalk,” “Swat the Fly” and “Bat the Rat.”

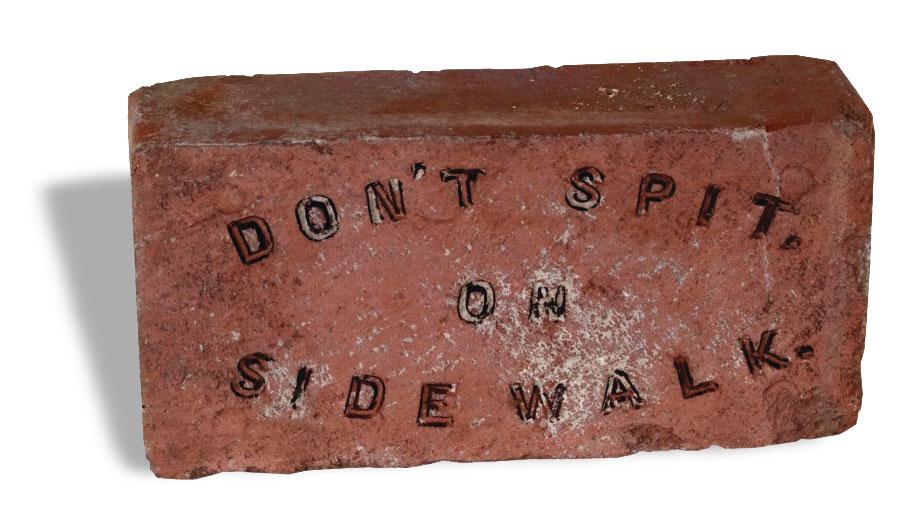

The Ford County Kansas Historical Society reported that the impetus for the first of the preceding admonitions followed Dr. Crumbine’s observation of a TB patient spitting upon the floor of a passenger train. The anti-spitting slogan became so famous that a brick manufacturer in Topeka imprinted it on paving bricks to bring hopeful pause to potential offenders before spreading their germs.

Some say that Dr. Crumbine’s campaign against public drinking cups led to the 1912 entrepreneurial development of a cone-shaped, disposable paper “Health Kup,” manufactured in Boston by the Individual Drinking Cup Company. This product was sold for a penny to hospitals and schools, and was eventually a standard item on trains. The 1918-19 Great Flu Pandemic created an even larger demand for the disposable cup; and in 1919, the “Health Kup” became the “Dixie Cup.”

Eventually becoming the dean of the University of Kansas Medical School, Dr. Crumbine died in 1954, while living near New York City. The Crumbine Consumer Protection Award, established in 1955, is now awarded annually by the food and drug industry to organizations that demonstrate achievement in the promotion of food protection and public health.

My stethoscope is off to this great physician. Dr. Crumbine probably saved vastly more lives as a public health pioneer than he ever saved as a clinical physician.

Photo Gallery

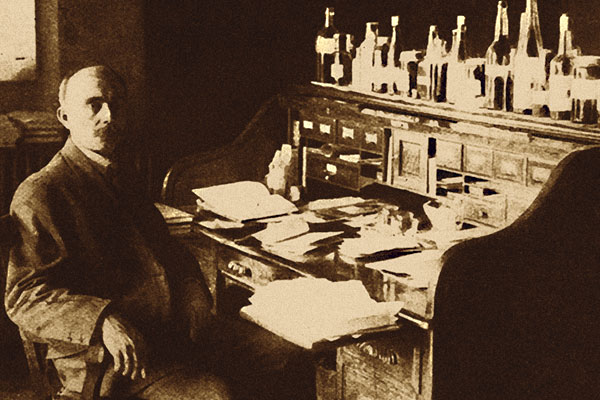

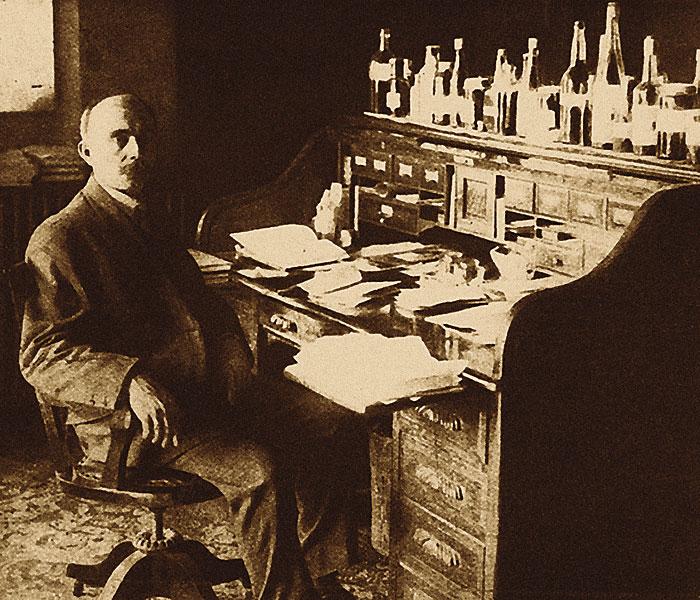

Dr. Samuel Jay Crumbine, seated at his desk in 1911, became famous for his public health slogans, such as “Don’t Spit on the Sidewalk.” The sidewalk brick shown in the next photo is in the collections of the Kansas Museum of History in Topeka, Kansas.

– Courtesy Kansas Museum of History –