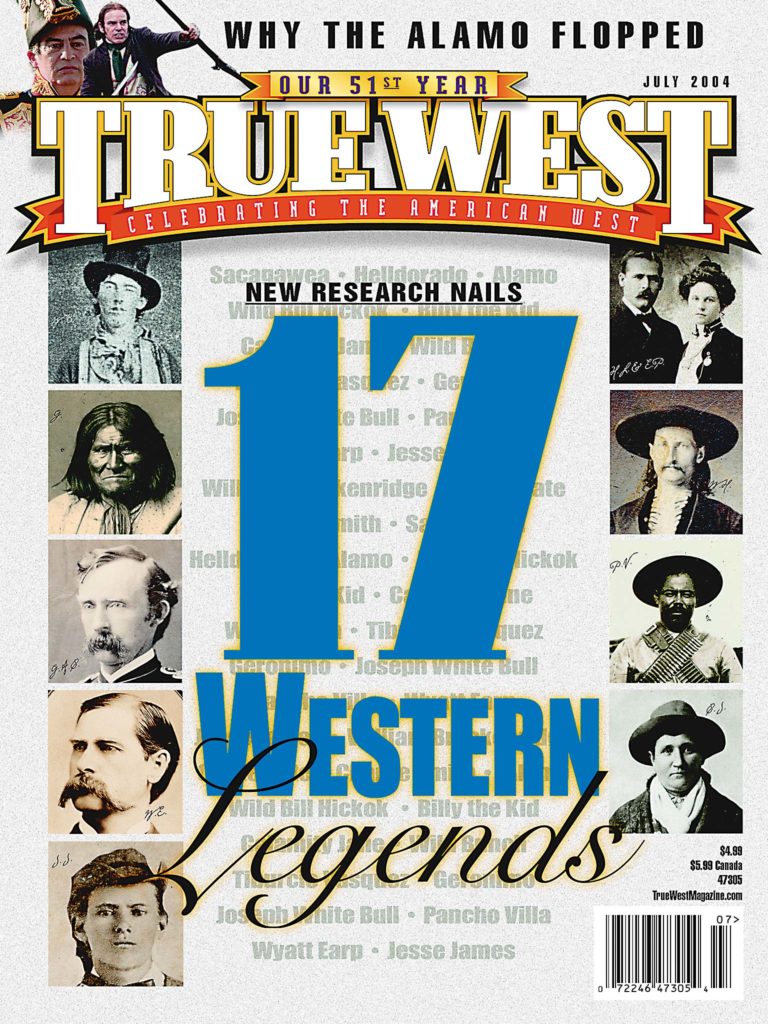

![]() They’re larger than life, these men and women of the Old West who are part of America’s history and its legacy.

They’re larger than life, these men and women of the Old West who are part of America’s history and its legacy.

They were bigger and braver, outrageous and bodacious, mean and mighty—take your pick.

If history were static and if icons were honestly painted, we’d already know everything about them, but it isn’t and we don’t. Our selective reading of history has made villains of heroes and heroes of villains, and it will always be that way.

But that doesn’t stop us from always searching, always trying to get closer to the truth.

True West went looking for the latest revelations about our Western icons. And we weren’t disappointed.

William Breakenridge Exonerated

It’s time to end the blasphemy against William Breakenridge, says historian Neil Carmony, who still lives near Tombstone, Arizona, and is noted as a careful researcher. Breakenridge was a deputy sheriff in Tombstone during its most turbulent days who has long been snubbed by Wyatt Earp fans.

A couple years ago, Carmony was writing an article about Tombstone when he mentioned the oft-repeated tale that Breakenridge’s 1928 “autobiography” was actually ghostwritten by a famous novelist of the day, William MacLeod Raine.

The book, Helldorado: Bringing the Law to the Mesquite, has often been belittled or dismissed because of the ghostwriting “fact,” which was handy for lots of Earp enthusiasts who didn’t like what it had to say about their favorite brothers.

Helldorado surmises that the Earps and Doc Holliday were fueled by some nasty intentions when they took that walk down to the O.K. Corral. Breakenridge isn’t the only one, but he certainly makes it clear he never believed the Earps were the dispassionate lawmen they pled after the bloody gun battle. But so what, if some fiction writer actually wrote the book anyway.

Carmony says he started wondering why everyone was so sure of this, and began tracing back the references to ghost-writing. There it is in Glenn G. Boyer’s 1976 book, I Married Wyatt Earp; there it is in Casey Tefertiller’s 1997 book, Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend; there it is in the latest tome on Wyatt by Timothy W. Fattig, published in 2002. In fact, Carmony found that virtually every book or magazine article that mentioned Helldorado claimed it had been ghostwritten.

“But it’s absolutely false,” says Carmony, with the gotcha of a man who knows how to research. He reports that he kept tracing back and eventually found a treasure trove to prove Breakenridge wrote his own book. Carmony did it by going to the original files of the publisher, which he found in the Houghton Mifflin Collection at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

He found Breakenridge’s first draft of the memoir dated 31 March 1927; he found the original approval for the project dated 11 May 1927; he found the final publishing contract dated 21 March 1928. In all, Carmony found 177 letters and telegrams between Breakenridge and Houghton Mifflin spanning March 1927 to December 1928.

“The oft-repeated claim that Raine ghostwrote Helldorado is a classic example of how, once in print, bogus ‘facts’ can spread like a virus throughout the literature,” Carmony says.

Big controversies continue in Jesse James circles

Researcher and author Nancy Samuelson (Shoot from the Lip: The Lives, Legends and Lies of the Three Guardsmen of Oklahoma and U.S. Marshal Nix) has uncovered new information that Jesse’s brother Frank and his wife had a baby daughter who died in infancy. It has been known that Frank had a son named Robert, but the existence of a daughter was unknown. Some James historians, especially Phil Steele, are unconvinced the report is authentic.

Meanwhile, James expert and author John Koblas reports that a DVD version of his controversial book The Jesse James Northfield Raid: Confessions of the Ninth Man (claiming the First National Bank heist was carried out by nine rather than eight robbers) has been finished and is in post-production for a summer release. ECM films out of Augustine, Florida, put the finishing touches on the project, which was originally helmed by Derk Hansen’s Saddle Tramp Studios.

Koblas also told us his newest James-related book is going to be called Bushwhacker! Cole Younger & The Kansas-Missouri Border War and will be published by Northstar in June.

On the first weekend in September, a huge Jesse James confab is shaping up in Northfield, Minnesota. A panel of experts, including John Koblas, Ted Yeatman, Chip DeMann and a Jesse James relative, is scheduled. If you’re into the James-Younger Gang, this is going to be a barn burner.

Calamity Jane Revised

Sometimes even the best book on an icon’s life contains serious errors that paint a distorted picture, and that’s what’s happened to Calamity Jane.

Roberta Beed Sollid’s 1958 biography is widely regarded as the best book on the life of Martha Jane Cannary—it includes interviews with people who knew her and was painstakingly researched—but even she got some things wrong, says Professor James McLaird, the leading expert on Calamity, who has his own book in the works.

Sollid underscores Calamity’s reputation as a loose woman with the claim that she was arrested for fornication.

McLaird says there was no such arrest. The documents Sollid relies on to make her claim “actually refer to Annie Filmore, known as ‘Calamity Jane No. 2’ in Montana,” he reports.

McLaird says he’s read virtually all the newspapers existing in Montana, Wyoming and South Dakota between 1875-1903 and has found a couple other interesting tidbits about the woman who’s been called everything from “The West’s Joan of Arc” to nothing but a common “whore:”

• She was born in 1856, not 1852 as she claimed.

• She was married at least once and had two children, one who died in infancy and a daughter who lived into the 1960s.

• The so-called “diary and letters” supposedly written by Calamity to her daughter were actually produced by Jean McCormick, an imposter who claimed to be the offspring of Calamity and Wild Bill Hickok. (A dead giveaway, McLaird notes, is that Calamity never learned to read or write. Her “autobiography” was told to a ghostwriter.)

But one thing never changes. Her 1903 obituary in The New York Times called her “the most picturesque character in the West,” and for many, she will always be.

Tombstone’s Nickname

For all the fame and infamy of Tombstone, Arizona, did you know it inspired a new word? “Helldorado” is a clever takeoff of the Spanish “El Dorado” (translated as “the gilded one”): the glorious locale with fabulous riches that the Spanish conquistadors expected to find in the New World. Hundreds of years later, some clever wordsmith in Tombstone coined the phrase “Helldorado” to mean a place where you’d find more trouble than riches. And the word lives on to this day, as Tombstone annually celebrates Helldorado Days.

Hickok’s Mystery Trip

We’re still wondering: Why did Gen. Philip Sheridan order Wild Bill Hickok—who’d served the Union Army during the Civil War as a wagon master, scout and spy—to Chicago in March 1869? Hickok expert Joseph Rosa says confirmation of that summons came to light only recently, when letters from the estate of Hickok’s sister, Celinda, went on the auction block. “To date, the reason for that summons has not been found, but I’m on the trail,” Rosa adds.

Who killed Billy the Kid?

The eight-paragraph letter, written December 22, 2003, hit like a bombshell.

In earnest language, it told a shocking first-person story that rocked the foundation of the West’s most famous icon: Pat Garrett’s widow had admitted her husband didn’t kill Billy the Kid!

The writer was Homer D. Overton, who lives in California. The letter was submitted to the Sixth Judicial District Court of the State of New Mexico in a case that carries a boring number but boils down to a most exciting proposal: “Dig up Billy the Kid.”

In the midst of legal wrangling—everyone now has an attorney, from Billy to his mother to the sheriffs of two New Mexico counties—came a letter that pushed the story back onto front pages across America.

Overton wrote that he was born in 1931 and spent his ninth summer in 1940 visiting a friend in Las Cruces, New Mexico. “The time I spent there was wonderful, but one thing happened that summer that made the summer unforgettable,” he wrote to Lincoln County Sheriff Tom Sullivan, who included the letter in his “Probable Cause Statement” in the case.

The next door neighbor that summer was a lady who’d invite the boys over for iced tea with mint leaves; she had a parrot that had belonged to her husband and by now she was very old. One day she brought out a gun her husband had owned, if memory served, it appeared to be a Colt Single Action Army revolver.

“At that point I asked her if that was the gun used to kill Billy the Kid,” Overton wrote. “At this point she got an unusual look on her face and stated she was going to tell us something we would have to promise to keep a secret, and never tell anyone. We both promised and until this day I have never told anyone but my immediate family.

“Mrs. Garrett proceeded to tell us the following facts concerning her husband and Billy: Mrs. Garrett said, ‘Pat did not shoot Billy.’ She said there was a very close relationship between Pat and Billy, almost like a father and son relationship. She further states that the night Pat was supposed to kill Billy, that they were in Ft. Sumner and had made a plan to make it look like Pat killed Billy so Billy could go to Mexico and live with no one looking for him any more. She said that Pat had seen a drunk Mexican lying in the street on his way to talk to Billy, so they planned to use the Mexican and claim he was in fact Billy the Kid. She didn’t state if the Mexican was dead or not, but said that they shot him in the face so he couldn’t be recognized. Then they dressed him in Billy’s clothes and Pat signed a paper for the Texas Rangers stating that he had killed Billy the Kid and that this was his body. The Mexican was then buried at Fort Sumner and identified as Billy.”

He had remembered the scene all these 63 years, recalling Mrs. Garrett seemed so sincere, and he was sure she was telling “the absolute truth.”

Whatever Mr. Overton is remembering, it’s not an afternoon with Mrs. Garrett.

True West went to the New Mexico Vital Records and Health Statistics office, requesting a copy of the death certificate for Apolinaria Gutierrez Garrett, the widow of Sheriff Pat Garrett.

The Certificate of Death attests that she died October 21, 1936—nearly four years before Mr. Overton’s startling, but inaccurate, memory of Mrs. Garrett’s story.

Tiburcio Vasquez was no Robin Hood

In some eyes, California bandido Tiburcio Vasquez is seen as a “social bandit”—a champion and avenger

for justice—but historian John Boessenecker sees him as a sociopath without any noble motives.

For instance, Boessenecker notes, Vasquez first went to prison for stealing a mule and nine horses from a fellow Hispanic—a crime to which he confessed. Furthermore, he was known to rob and murder both Anglo and Hispanic alike. “In 1867 Vasquez entered San Quentin for his final prison term,” Boessenecker writes. “All later writers … have claimed that this prison sentence was for cattle rustling, a crime which is generally associated with the Hispanic social bandit. But … [they are all] mistaken. In fact, Vasquez was imprisoned for breaking into the Sargent & Barnes store in Petaluma—the act of a petty burglar and sneak thief, not that of a primitive rebel or revolutionary.”

“People of all cultures love the image of the romantic, elusive outlaws,” Boessenecker notes, and so he fully expects the myths about Vasquez to continue.

Cattle Kate Wrongfully Hanged

Was “Cattle Kate” really the cattle rustler who deserved to be hanged in Wyoming in 1889, as history has long recorded? Or was her lynching “the most revolting crime in the entire annals of the West,” as one historian has claimed?

Cattle Kate was really Ella Watson, who had a small ranch near the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, not far from her friend Jim Averell. As historian Dorothy Gray reports, both ranches were surrounded by land claimed by one of the biggest cattlemen of the Wyoming Stock Grower’s Association. The association was intent on scaring off smaller ranchers to have the land for themselves. But neither Averell nor Watson scared easily.

On July 20, 1889, a party of stockmen kidnapped the two and lynched them.

“No sooner was Ella Watson dead than the stockmen started a press campaign in which she was transformed into ‘Cattle Kate,’ characterized as having not only rustled more cattle than any man in the West but as having been a prostitute, husband-poisoner, and hold-up artist,” Gray notes. She contends it was all a lie to steal the woman’s land.

G.D. Texans

If you think profanity is a new thing, consider this: Mexicans attacking the Alamo called the Americans inside “The God damns,” because those were the words they heard the Americans yelling most often to one another.

Alamo Reinforcements

Alamo expert Paul Hutton reports that “new research suggests there were more Texan defenders than we once thought [180] and that there may have been 200 to 250. These men were reinforcements that got in from Goliad and are usually listed with the Goliad dead.”

Furthermore, he says, “It is also clear from Mexican cavalry reports that up to 60 defenders made a break and tried to cut their way out. [General] Sesma’s lancers killed them all.”

Pancho Villa mixes it up

Tom Mix and Pancho Villa may soon be coming to the big screen. Director Tony Scott has long wanted to make the Clifford Irving novel into an epic film and he’s now scouting locations in Mexico.

“This is Lawrence of Arabia meets The Wild Bunch, a huge film with trains, cavalry, thousands of soldiers in uniform and on horseback,” Scott says. “This is a love story between two men from different planets, who educated each other. Pancho Villa knew the laws of life, and Tom Mix knew how to live in a modernized Western world.”

Scott says he’s worked for a dozen years to tell the story of the idealistic actor who leaves the comforts of Texas to join up with a revolutionary who would not embrace modern technology.

Historians are split on whether the novel is based on a true story or a Hollywood myth.

Old West Myth Debunked

So you think the West was nowhere near as violent as popular culture suggests? Then you should check out Gregory Michno’s Encyclopedia of Indian Wars (Mountain Press, 2003). As historian Paul Hutton notes, “One of the trendy academic mantras Michno finishes off is the contention that the West was not a violent place—he proves just the opposite.” Hutton says the book is most valuable in giving a clear picture of the Indian Wars.

Wild Bunch Misnamed

The Sundance Kid didn’t have a lover named Etta. Her name was Ethel. “The Pinkertons mangled it Etta on their wanted posters, and so Etta she became,” report Wild Bunch experts Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows. And while we’re at it, they’d like to clear up that Wild Bunch title—the name was never even used to describe the gang until after it had ceased to exist. “During its heyday it was known in the newspapers as the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, the Robbers Roost Gang, the Train Robber’s Syndicate, and other headline-friendly monikers,” they note. “In fact, the confusion of names is a clue that it wasn’t as much a single gang as different outlaws joining up at different times.”

Who killed Custer?

Joseph White Bull—nephew of Sitting Bull—may be the warrior who killed George Armstrong Custer.

The Dakota warrior was 26 years old when he fought at the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, a point that history doesn’t dispute. Years later, in a “ledger book,” he produced drawings and text that recounted his encounter with Custer. But that document would remain secret until long after White Bull’s death. When it emerged in 1960, some were convinced his story was authentic, whereas others thought he was talking about killing someone other than Custer.

Ironically, Chief White Bull was the one chosen as the “Representative of the Red Race” who led Indian warriors onto the Little Bighorn battlefield in 1926 for the Golden Anniversary ceremony.

Wyatt Earp fingered

Was Wyatt Earp a pimp?

Evidence just discovered last year makes it clear that on February 26, 1872, Wyatt and Morgan Earp were each fined $20 for “being found in a house of ill fame” in Peoria, Illinois—a house that the city directory at the time listed as Wyatt’s residence.

History has long claimed Wyatt spent 1872 hunting buffalo on the Kansas plains.

But does that arrest mean Wyatt was a pimp, or as his defenders claim, merely a bodyguard or bouncer?

New records show that Wyatt was arrested yet again in a Peoria brothel raid in September 1872. This time, his fine was almost twice the amount levied against any of the other 12 people nabbed that night—and the Peoria Daily Transcript newspaper singled Wyatt out as “an old offender.”

Charlie Smith fakes Doc Holliday’s passing

For a while there, we thought we had a bedside seat at Doc Holliday’s death in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, on November 8, 1887. But alas, the “Charlie Smith letters” that detailed Doc’s last minutes are a fake.

Geronimo profits on his fame

It didn’t take Geronimo long to understand the value of being a celebrity.

In 1898, Geronimo and a number of other Apache men, women and children were invited to the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska. As they journeyed east by train, Geronimo got off at various stops and sold buttons off his coat for 25 cents each. For five dollars, he’d sell his hat. Then he’d get back on the train and diligently sew more buttons on his coat—and pull another hat from his ample supply.

At the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, he recalled selling his autograph and photograph. “I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money—more than I had ever owned before,” he’d later recall.

In 1905, Geronimo was invited to ride in Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. The army sent him an expense check for $171. He put $170 in his bank account at home and boarded the train east with $1 in his pocket. At every stop, he made money selling his autograph. At the parade, Geronimo was a runaway hit, which angered some folks who thought of him as a renegade and murderer. When Roosevelt was asked why he put him in the parade, the president answered, “I wanted to give the people a good show.”

Geronimo had undoubtedly become a national celebrity.

When Sacagawea died

When and where Sacagawea died has long been an Old West mystery. In January 2003, True West called it one of “two important things we don’t know about Sacagawea”—the other being the correct spelling of her name, of which there are at least three variations.

Even the North Dakota Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center in Washburn isn’t certain, and this spot comes as close to a “hometown” to the famous Indian woman as anywhere—the center is near the site of Fort Mandan, where the American explorers built their winter camp in 1804 and where Sacagawea gave birth to her son, Pomp.

But even this interpretive center allows there are conflicting stories about Sacagawea’s death. The center notes that most historians believe she died December 20, 1812, at Fort Manuel in South Dakota when she was 25 years old, but adds that others think she lived into her 90s, dying in Wyoming in 1884.

So it struck like a bolt when a footnote to a story on Sacagawea answers the question once and for all.

Historian Dorothy Gray’s 1976 book Women of the West notes in a footnote that the principle source of the Sacagawea living-to-be-an-old-woman version came from a 1932 book by Grace Hebard. “Ms. Hebard’s work however includes records of the period … which actually argue strongly that Sacajawea died in 1812,” Gray writes. And then she lays down the zinger that should finally settle this issue:

“Confirmation of this earlier date would appear to come from [William] Clark himself who wrote a list of the party members in about 1828 and noted, ‘Se car ja we au Dead.’”