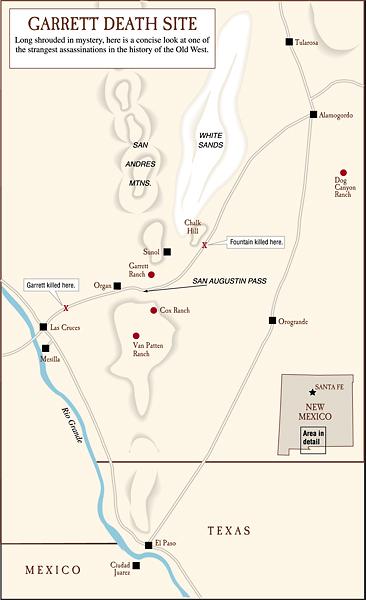

For the 57-year-old lawman, his was an undignified death. Pat Garrett was urinating on the side of the road to Las Cruces, New Mexico, about four miles east of town. As he was so occupied, somebody hidden about 50 feet behind him put a Winchester bulletin the back of his head.

For the 57-year-old lawman, his was an undignified death. Pat Garrett was urinating on the side of the road to Las Cruces, New Mexico, about four miles east of town. As he was so occupied, somebody hidden about 50 feet behind him put a Winchester bulletin the back of his head.

One of his two companions placed the dead man’s Burgess folding shotgun—still in its sheath—near the body. Then the pair headed to town to tell a fairy tale about the incident.

On February 29, 1908, Garrett was dead. The man who had headed down the legends trail nearly 30 years before when he killed Billy the Kid, murdered.

It was a conspiracy. A contract murder. An organized crime hit.

This is what we know.

Organized Crime in New Mexico Territory

Yes, organized crime was present in New Mexico in 1908. It had been for more than 30 years at that time.

Early on, the Santa Fe Ring, a Republican organization led by major domo Thomas Catron, gobbled up land by hook or crook, cornered U.S. Army beef and horse contracts, monopolized banking and merchant industries—and was willing to kill to protect its turf. The wars in Colfax and Lincoln Counties showed that.

By around 1890, a Democratic counterpart had taken over in southeast New Mexico and into El Paso. Led by super lawyer and political boss Albert Fall, this group also accumulated land and water rights by any means necessary. They engaged, individually or collectively, in bribery, influence peddling, rustling, intimidation, jury tampering, assault and murder. A couple of them did a little robbery on the side.

All that brought a Democratic crime ring into direct conflict with a Democrat-turned-Republican lawman named Garrett—and set the stage for his ultimate assassination.

The Conspirators

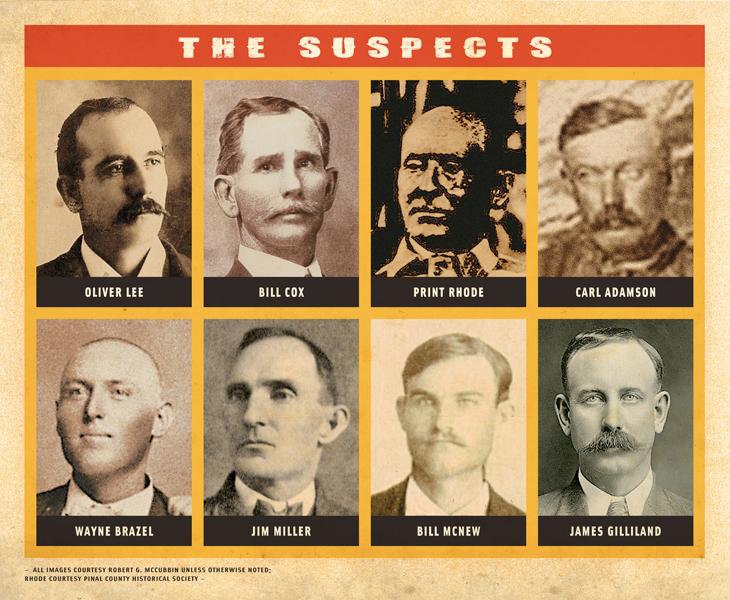

Historians are unsure who exactly was involved in the plot to kill Garrett. A few names are known, but undoubtedly others played a role. They all had axes to grind with Garrett.

Like the modern mafia, this group was based on family. Ranchers (and suspected rustlers) Oliver Lee and Bill Cox were wed to sisters of strong-arm man Print Rhode. Rancher (and smuggler) Carl Adamson was married to gunman and corrupt lawman Mannie Clements’s sister—who herself was a cousin-in-law of hired killer Jim Miller. All had various partnerships, legal and otherwise, with one another.

Various members of the plot had specific reasons for wanting Garrett dead.

Take, for example, Lee and Bill McNew. Most folks believed they were involved in the disappearance and killing of Col. Albert Fountain and son Henry in 1896. Fountain had been about to prosecute Lee for rustling; the indictments disappeared with him. As sheriff of Doña Ana County, Garrett decided to arrest the pair and their cohort Jim Gilliland for the Fountain murders. At one point, Garrett and a posse ended up in a gunfight with Lee and Gilliland in which a deputy was killed. The pair eventually did surrender to the authorities (not Garrett) and were found not guilty in the killing of Henry Fountain; nobody was tried for killing Albert Fountain, so the case remained open. Garrett wasn’t satisfied and continued looking for evidence against the trio, even after he gave up his badge in 1900. Lee and his pals feared that Garrett might find something—or that he would kill them as he had Billy the Kid.

Carl Adamson and rancher W.W. “Bill” Cox were other possible suspects, as they had reportedly wanted Garrett’s land for water rights, grazing of their herds and so forth.

Rhode hated Garrett. The sheriff had tracked a wanted killer-—and friend of the Cox/Rhode clan—to the Cox ranch in 1899 and killed the suspect while trying to arrest him. Rhode’s sister was present and subsequently miscarried a baby; Print blamed Garrett. To make matters worse, Garrett arrested Rhode the next year in connection with a holdup. Rhode was acquitted, but he wanted vengeance—and he figured that when it came to Garrett, it was kill or be killed.

Albert Fall, a gifted trial attorney and businessman, had connections with all of the conspirators. If Garrett brought down part of the criminal enterprise, he might just catch Fall, the outfit’s godfather. That would have been enough for Fall to want Garrett out of the picture.

Throw in another factor—Garrett owed money. Lots of money, to lots of people, including some of the conspirators. He was not good on paying back his debts. The plotters may have figured that killing Garrett would send a message to others who might renege on their financial responsibilities.

A final motive for murdering Garrett has come up in the last 20 years, especially through the work of New Mexico Mounted Police chronicler Chuck Hornung. The conspirators were involved in a ring that smuggled Chinese workers and perhaps narcotics into the U.S. Garrett’s Bear Canyon Ranch was a perfect spot for a way station on the smuggling trail. The ring wanted the land—and didn’t want Garrett snooping into their illegal activities. They first tried to get it by legal means—Bill Cox took advantage of Garrett’s bad financial situation to buy up the note on his ranch. But efforts to evict or pressure him to leave failed.

The Plan

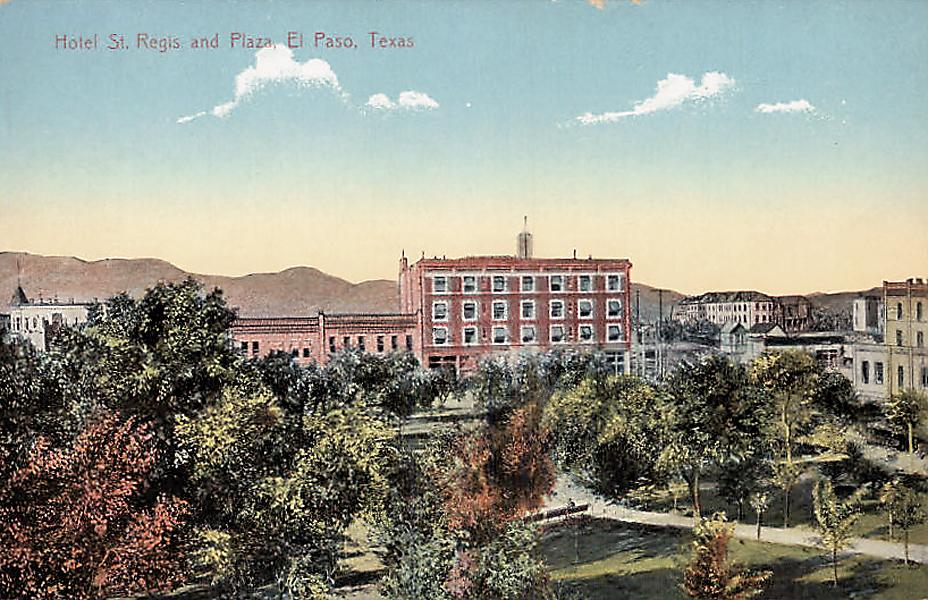

Sometime in the fall of 1907, several conspirators met at the Hotel St. Regis in El Paso, Texas. Among those reported in attendance: Cox, Adamson, Lee, McNew, Miller, Wayne Brazel and possibly others (maybe Fall, according to statements by Lee’s son). The men came up with a plan to kill Garrett—and hired Miller to do the job for $1,500 provided by Cox.

But first, the crew set the stage for the killing. Brazel was tasked with leasing some Garrett property (which was actually in the name of Garrett’s son Poe). Brazel moved goats onto the land, which enraged a cattleman like Garrett, since the goats would destroy the grazing grass and kill the property value.

Garrett tried to convince Brazel to move off his property. Brazel refused, of course, and Garrett was stuck. That is, until Adamson and Miller came forward, offering to buy Brazel’s herd and the Garrett land. Desperate for money, Garrett agreed. To get all the details worked out, the four men—Garrett, Brazel, Adamson and Miller—agreed to meet in Las Cruces, New Mexico, on February 29, 1908.

A flurry of telegrams passed among Adamson, Brazel, Miller, Cox and Rhode on February 28, perhaps confirming details of the plot. That night, Adamson went to the Garrett house to spend the night; the two would leave early the next morning. Before bedtime, Brazel showed up with a message for Adamson (the Garrett family came to believe that the note had final instructions on the hit).

That same night, Miller left El Paso, Texas, and traveled to a ranch near Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he caught some shut-eye. The foreman there would later claim that Miller borrowed a horse, saying that he needed it to go kill Garrett.

Adamson and Garrett headed out in a buggy at first light on February 29. Brazel, on horseback, met them on the road—but only after he was seen conferring with an unidentified rider (the shooter?), who left before Garrett and Adamson got there. The trio made one stop at the town of Organ; a bystander there said that Garrett was arguing with Brazel over the goats, further establishing the goat rancher’s later claim of self-defense.

The trio continued on until they reached a pre-arranged spot just a few miles outside Las Cruces. The shooter was already in place on a hillock, hidden from view. Adamson said he had to stop to relieve himself; Garrett decided he did too.

That was when the shooter put a bullet in the back of Garrett’s head. The second shot to the gut was overkill.

After the deed was done, the killer hightailed it away, leaving behind a Winchester shell, hoofprints and horse droppings. Brazel and Adamson went to Las Cruces and reported their version of events to the sheriff’s office. Brazel was taken into custody in the death of Garrett.

The Investigation

Frankly, a lot of folks had trouble believing that Brazel shot Garrett. The two had known each other for years, and friends of Brazel were convinced that he couldn’t hurt a fly.

New Mexico Mounted Police Capt. Fred Fornoff—who was not a Garrett friend or fan—requested a thorough investigation. But without money for it, Gov. George Curry, ostensibly a friend of Garrett, didn’t seem interested in supporting the effort. During this period, certain members of the legislature unsuccessfully tried to disband the mounted police or cut its funding. Fornoff was convinced that the bill’s sponsors were trying to block the official inquiry.

Territorial Attorney General James Hervey—whose father was a Garrett friend, and who apparently felt an obligation to get to the truth in the case—tried to raise private money to continue the investigation…and got nowhere. Powerful and wealthy Garrett associates, including El Paso saloon owner Tom Powers, declined to pony up. Western novelist Emerson Hough, who had consulted with Garrett for his book The Story of the Outlaw, also said no. The writer had some advice for Hervey: “Jimmie, I know that outfit around the Organ Mountains, and Garrett got killed trying to find out who killed Fountain, and you will get killed trying to find out who killed Garrett. I would advise you to let it alone.”

Ultimately, that was just what folks did. It was too dangerous to ask questions.

The Trial

The Territory of New Mexico vs Wayne Brazel was a sham, a setup. The verdict was a foregone conclusion.

In the trial held from April 19 to May 4, 1909, Fall defended Brazel. The prosecutor was Mark Thompson, a Fall ally. The judge was Frank Parker, who had presided over the Fountain murder case; it was known that he and Garrett didn’t get along. Parker, too, was a friend of Fall’s.

When he testified, Brazel claimed that he and Garrett had argued about the goat issue on the road to Las Cruces. Garrett became increasingly angry and threatening. When Adamson stopped the buggy to answer nature’s call, Garrett went for his shotgun—and Brazel killed him in self-defense.

District Attorney Thompson did nothing to prove the territory’s case. He didn’t call the only eyewitness, Adamson, to the stand. Coroner W.C. Field did testify, but he was not asked about the entry and exit wounds on Garrett’s body. The jury never heard that Garrett was urinating when he was killed, or that he was shot in the back of the head, or that his shotgun was holstered and unloaded.

Within just 15 minutes, the panel issued a “not guilty” verdict. Afterward, Cox had a celebratory cookout at his ranch.

So, Who Killed Garrett?

Special investigator Cipriano Baca believed that accused Fountain murderer McNew was the guilty party.

Jarvis Garrett, Pat’s youngest son (who was only two when his father died), came to the conclusion that Adamson was the killer.

Some folks thought Brazel himself did the deed and got away with it.

But the top two candidates these days are Rhode and Miller.

Mark Lee Gardner, in his excellent To Hell on a Fast Horse, builds the Rhode case. Rhode had the motive—a longstanding fear and hatred of Garrett. He was in the area at the time of the shooting. Two of Rhode’s nephews, Oliver Lee Jr. and Jim Cox, suggested later in life that Rhode had shot Garrett. And an anonymous note sent to Garrett’s daughter Annie also named Rhode as the assassin. According to this theory, Brazel took the rap because Rhode had kids—and because Brazel had been assured that he would never see a rope or a prison cell.

Then there’s Miller, the man known to history as “Killin’ Jim,” perhaps the most prolific hit man of his era. Miller biographers Ellis Lindsey and Jerry Lobdill (each working on Miller books) both believe he pulled the trigger on Garrett.

So do I.

A group of men met at the St. Regis Hotel in El Paso, Texas, with the express purpose of hiring Miller to kill Garrett. Oliver Lee Jr. said as much, though he also said that Rhode acted before Miller could complete the contract.

Miller was one of the parties who offered to buy Garrett’s ranch from him. He was in the area at the time of the shooting. Miller met with Brazel in El Paso not long before the killing—Lindsey thinks the assassin was coaching the patsy in what to say.

New Mexico Mounted Police Capt. Fornoff, who had investigated the case as much as he could, said that a wealthy rancher (Cox) had paid Miller $1,500 to kill Garrett—and that Miller did it. Territorial Attorney General James Hervey believed the same thing, as reported in True West’s March-April 1961 issue.

Adamson, on his deathbed in 1919, reportedly told his young grandson that he and others had hired Miller, who proceeded to murder Garrett.

What about the assertions by the sons of Lee and Cox that Rhode was the killer? Their stories essentially cleared their fathers of the killing—sure, they hired Miller, but he didn’t actually shoot Garrett, so they weren’t guilty of murder for hire. Family protects family…except for their uncle Print.

At that time, people just didn’t mess with Miller. He had a reputation, and folks feared him. Does it seem likely that a person—even one as angry and violent as Rhode—would dare take the chance of crossing Miller? Not hardly.

Bottom line: a number of men—powerful and successful men involved in organized criminal activities—were behind the assassination of Garrett. He had made too many enemies, and he posed too much of a threat to their lives and livelihood. All were guilty, even if they never faced a judge and jury. The crime syndicate led by Fall got its way.

But Miller pulled the trigger on Garrett. It was a story he took to his grave 14 months later. Somewhere, maybe in Hell, Billy the Kid was smiling….

Photo Gallery

– True West archives –

– Courtesy Center for southwest research, university of new mexico –

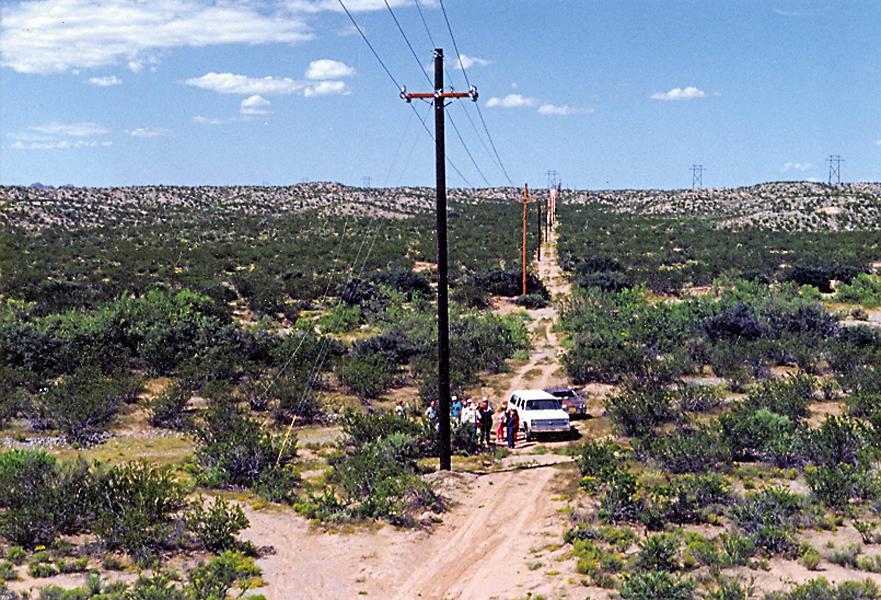

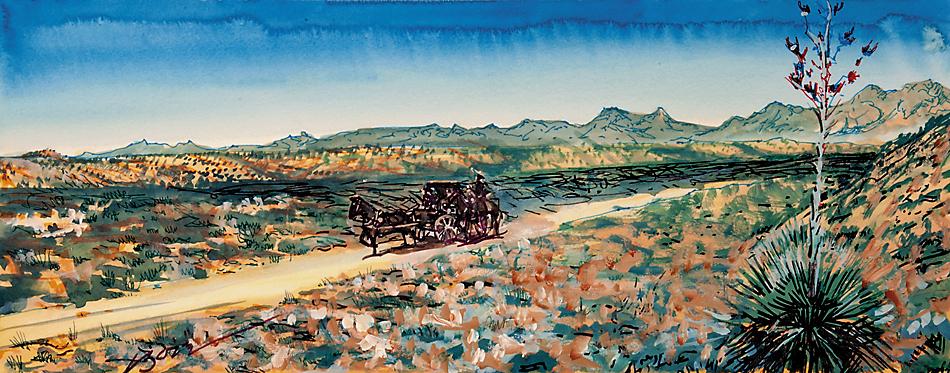

Pat Garrett made his last ride on the same road that Albert J. Fountain met his demise (search “Fountain Murder” in Classic Gunfights). As Garrett and Adamson rode in the buggy, Wayne Brazel rode alongside as the two argued over running goats on Garrett’s land.

At a prearranged site, Adamson asked to stop to take a leak and Garrett followed suit. While Garrett stood next to the rear wheel of the buggy, with his one glove off and in his left hand, a rifle shot, fired from behind, hit Garrett in the head, the bullet exiting his right eye.

One of the conspirators remarked the old lawman “fell like a sack of potatoes.” The next slide is a photo taken at the Alameda Arroyo site in 1991. The power pole service road is not the road Garrett was on and, in fact, runs perpendicular to the death road.

– True West archives –