As much as any Texas Ranger who served in the last half century, Joaquin Jackson knew well what fellow Captain C.J. Havrda meant about being a part of history. That was surely the case up until the day Jackson died of cancer on June 15 in Alpine, Texas. He was 80. The lawman was a part of history from 1966 to 1993, working thousands of cases across the Lone Star State.

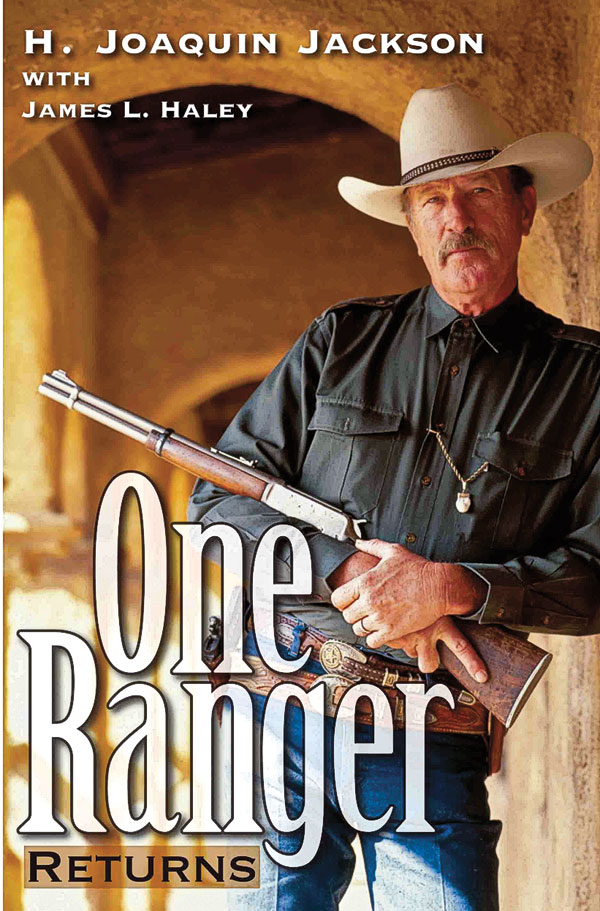

Jackson might have done as well at another point in history—say, in the real Ranger heydays. James L. Haley, who helped write Jackson’s second book, One Ranger Returns, says, “His love of open country, and horses, the thrills of chase, danger, adventure—he was aware that all those would have been heightened in the Old West. However, he certainly accepted that those days were over.”

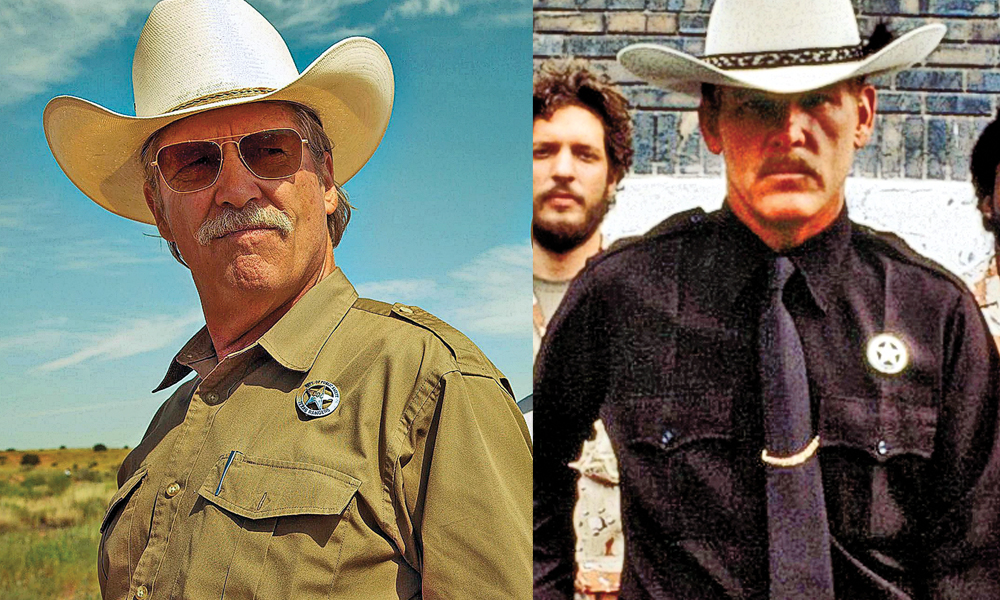

But it can be fun, maybe even instructive, to wonder: what if Jackson had served in the early 1900s, and legendary Ranger Frank Hamer had done his Ranger work in the 1960s through the early ’90s? Could they have switched places? The similarities between the two lawmen are striking.

• Both were Texas born and bred, cowboys who were born to the saddle and could handle a gun—just about any gun—with deadly accuracy.

• Both were big guys who used size, a booming voice and steely gaze to their advantage—and they had strong tempers.

• Both had experience in the Big Bend and Hill Country regions and did much work along the Rio Grande.

• Both had strong personal honor codes which included treating people

of all ethnicities and races fairly, having a compassion for the underdog and harboring a hatred of corrupt lawmen and officials.

• They dealt with similar issues—rustling, smuggling, mob actions, border disputes, voter fraud, robbery,and violent crime.

• Each occasionally cut corners to get the job done. Jackson admitted that he sometimes bribed Mexican officials to get a suspect sent back to the states, pronto. And Hamer, at times, took a “shoot first, ask questions later” approach when dealing with dangerous perps.

• Both adapted well to changing law enforcement technologies, including blood typing, DNA, computers and ballistics.

• Both ran afoul of bureaucracy and politics, both in the agency and state government.

Jackson himself never made that comparison, at least so far as we know. But he believed that modern Rangers could have done the job back then: “The storied Ranger heroes of days gone by, Leander MacNelly and John B. Jones and Bill McDonald and Frank Hamer, still have their equals today. To paraphrase Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, it is the times that have gotten small.”

Jackson himself never made that comparison, at least so far as we know. But he believed that modern Rangers could have done the job back then: “The storied Ranger heroes of days gone by, Leander MacNelly and John B. Jones and Bill McDonald and Frank Hamer, still have their equals today. To paraphrase Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, it is the times that have gotten small.”

The times, and maybe a bit more. Jackson remained a Ranger private his entire career so he could work in the field, not behind a desk. In Hamer’s time, captains spent much of their time out of the office, pursuing cases. Paperwork and administration weren’t as big back then.

Modern policies and procedures have also had an impact on how today’s Rangers perform their work. Hamer said he was in 52 gunfights in which 23 people were killed (not all while he was a Ranger, but most). Jackson was in a handful of shoot-outs and nobody died (which was fine with him). Rules on use of force have cut down on the times a Ranger pulls a gun and uses it in anger.

Maybe because of that hell-firin’ action, the old-time Rangers were in the public eye more–in newspapers, magazines, newsreels, dime novels. They celebrated the daring deeds of the Rangers, built them up to superhuman status. By the late 1920s, Frank Hamer was one of the best known lawmen in the country—and that was before he brought down Bonnie and Clyde.

When Jackson was in his prime, it was a different story. As an example, he wrote about a kid’s baseball game that he umpired. The boy at bat asked him what he did for a living, and Jackson told him he was a Texas Ranger. The boy then asked him what position he played—a reference to the Texas Rangers baseball team.

That took Jackson down a peg or two.

It needn’t have. Others, like his friend and colleague, former Crockett County (TX) Sheriff Jim Wilson, say Jackson was an excellent lawman whose only focus was on doing his job as best he could.

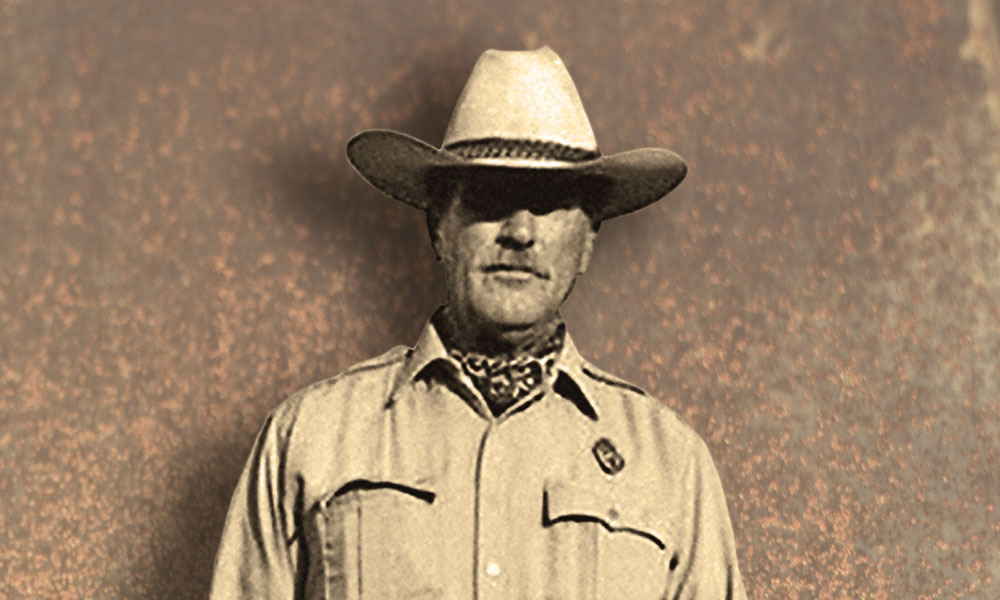

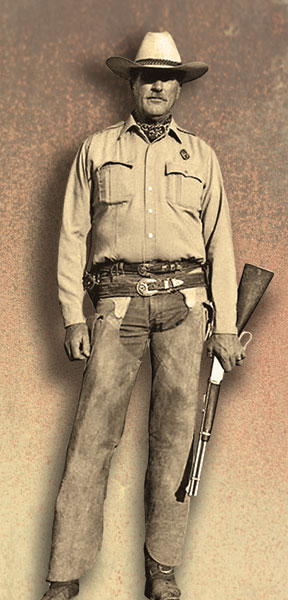

So it was ironic when Jackson became the cover boy for the February 1994 Texas Monthly magazine. It made sense in one way—the tall, lean, craggy/handsome guy with the hat and boots and chaps, a pistol on his hip and lever-action rifle in his hand, just looked like a Ranger. But Jackson had retired four months earlier. The bureaucracy and politics, the increasingly pain-in- he-butt rules, the acceptance of female Rangers who he considered unqualified, all played a role in his decision to quit. He was also tired of getting late-night calls at home, telling him to put his boots on and get to work.

But with that magazine article, Jackson suddenly became the face of the force and got more publicity than in his entire 27-year Ranger career.

Jackson took it in stride. He wrote two books, made numerous speeches and public appearances. He taught Hollywood stars like Jeff Bridges and Nick Nolte how to look and act like a Texas Ranger—and did some acting himself. It was a cottage industry that helped make his retirement years a bit more comfortable and a heckuva lot more interesting. It also made Joaquin Jackson the best known Ranger in the past 40 years or so. Again, after he turned in his badge.

But Jackson kept things in perspective. In his books, he gave more credit to his colleagues than he did to himself. He knew that he’d done his job, done it well and he took pride in it. “I was an active officer in the oldest and most legendary law enforcement agency in the United States,” he said. “As a Texas Ranger, I have always understood that I was part of a rich, proud tradition. I’d drain the last drop of blood from my body to uphold it.”