The Davy Crockett of American mythology was, as anyone who grew up in the 1950s watching Walt Disney’s TV show could tell you, born on a mountaintop in Tennessee. The historical David Crockett (1786-1836) hailed from North Carolina.

The Davy Crockett of American mythology was, as anyone who grew up in the 1950s watching Walt Disney’s TV show could tell you, born on a mountaintop in Tennessee. The historical David Crockett (1786-1836) hailed from North Carolina.

The mythic Davy fought single-handed through the Creek Indian War of 1813-14. The historical David grew so weary of combat that he paid a man to fulfill his final months of military obligation.

Davy headed off for Texas to engage in lighthearted fun hunting buffalo and in the more serious task of fighting for the cause of freedom. David traveled to the Southwest because his political career had hit rock bottom, he’d become estranged from his second wife, his finances were in disrepair and he hoped to kick-start his ruined life by acquiring the land and wealth that had always eluded him.

The mythic Davy went down fighting at the Alamo in Texas on March 6, 1836, swinging his rifle “Old Betsy” like some mighty club. The historical David more likely surrendered, along with a half dozen other men, to Santa Anna and was unceremoniously executed shortly thereafter.

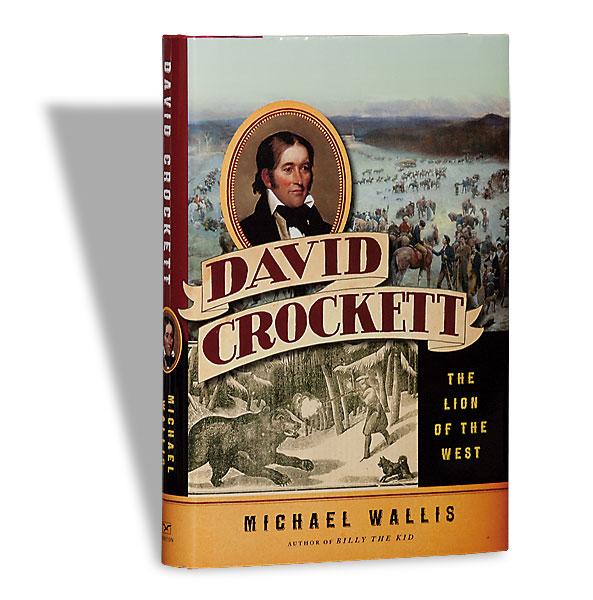

As Michael Wallis states toward the end of his splendid new biography, David Crockett: The Lion of the West (W.W. Norton & Co, $27.95), “There was the David Crockett of historical fact and there was the Davy Crockett of our collective imagination.”

Those two figures intersected at odd angles, in part because that person named David not only bore witness to the creation of “Davy,” America’s first pop-culture superstar, but actively participated in that act, if, in time, to his deep regret.

The Crockett you’ll meet in this volume has more in common with Billy Bob Thornton in the 2004 film The Alamo than either Fess Parker or John Wayne, the two actors most associated with the role in TV and film incarnations from the “good ol’ days.” These are different times; revisionism is the order of the day. He was called Davy then; David, now.

That’s all well and good, just so long as our heroes are not dragged down into the muck for cruel sport, but showcased as the flawed if fascinating people they were. Which precisely describes what Wallis has achieved here. His loving if critical (though never negatively so) tome does for Crockett what Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Star did for Custer: allowing us to see the man, warts and all, behind the myth; yet come away appreciating him more, not less, for having taken this well-researched journey.

To reverse the Bard, Wallis came not to bury Crockett but to praise him, if in soft whispers rather than a hoot and a holler. In the process, he allows us to grasp how a worthy if imperfect man provided raw material for what would emerge as America’s own variation on the mythic Hercules.

Check out Michael Wallis talking more about this book on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart on August 11, 2011.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Michael Wallis | ||||

|

||||

Photo Gallery

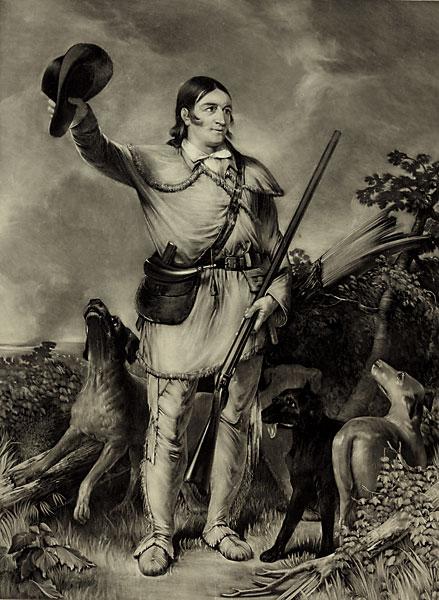

David Crockett is depicted with his three hunting dogs in this 1839 engraving by C Stuart from an original portrait by J.G. Champman. Crockett’s bear-hunting exploits and defense of farmers helped him win entry into Congress in 1827. In the winter of 1825-26, he told of how one black bear battered his dogs; but he crept up on the bear and stabbed him in the heart.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –