Wyoming cowboy and Army cavalry and horse artillery veteran Tim McCoy brought realism to the silver screen.

For a lad of Irish-born parents, his Michigan hometown, a lumber community, was too tame.

Young Timothy John Fitzgerald McCoy longed for excitement.

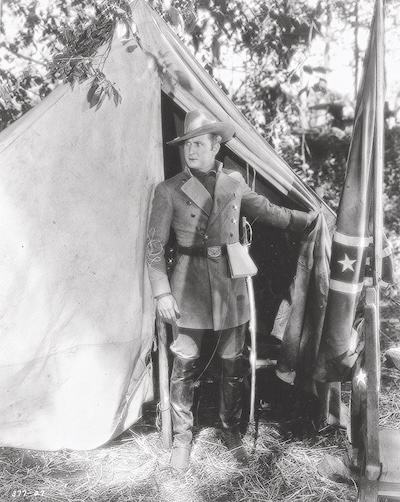

His father was a Civil War veteran. Smart uniforms with brass buttons and gold braid stirred his imagination. So, too, did the national hero of his day—the cowboy.

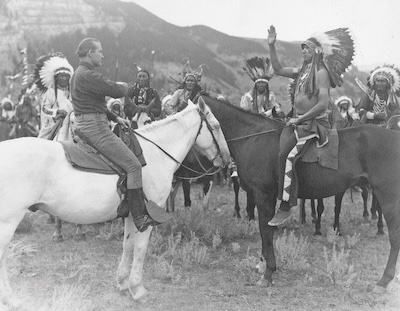

During late spring 1909, the 18-year-old left family and friends in quest of the West. After arriving in Wyoming, he learned to ride, rope, brand and became an able hand. He even acquired a small spread of his own, as well as learned sign language from the local Arapaho people whom he admired. In turn, they respected him. The Arapahos gave him the name “High Eagle.”

With the outbreak of the First World War, McCoy’s life took another turn. Filled with ideas of adventure and stirred by patriotism, McCoy, through a little Irish luck and blarney plus a pinch of persistence, secured a commission in the United States cavalry. When the machine gun, barbed wire and other modern martial technology spelled the beginning of the end for that branch of service, McCoy transferred to the horse artillery. After that, he spent his days as an officer at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. By the time of the 1918 Armistice, McCoy impressively had risen to lieutenant colonel, no mean accomplishment for someone still in their 20s! Besides securing rapid promotion, the youthful colonel also met Gen. Hugh Lenox Scott, who long before earned his spurs in the Indian Wars. McCoy and Scott developed a professional and personal friendship that lasted until Scott’s death in 1934. In the process, McCoy learned much about the “Old Army” on the frontier.

Courtesy MGM

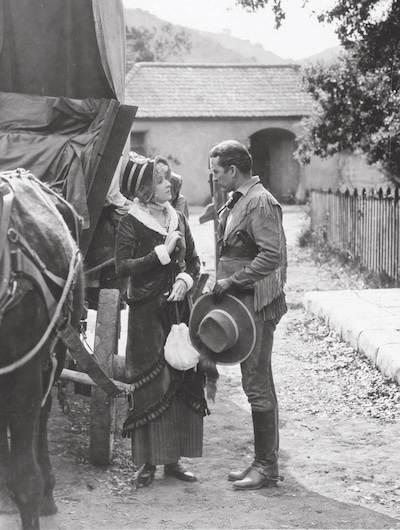

McCoy’s reservoir of experience made him an ideal advisor on one of the first major budget blockbusters of the silent era—The Covered Wagon (1923). The following year, he served in the same capacity for The Thundering Herd, which was filmed near Bishop, California, and in which McCoy had a small onscreen part as Burn Hudnall.

By 1926, MGM offered McCoy a three-year contract that launched his career as a star. His first featured role, War Paint, became a template for most of his movies with Metro. In the process, he blazed the trail for later make-believe U.S. cavalrymen including John Wayne, Randolph Scott, Richard Widmark and Matt Damon. In fact, more than half of McCoy’s 16 starring roles, between 1926 and 1929, cast him as a military officer. (McCoy’s 1926-29 non-military films were The Adventurer, Beyond the Sierras, The Bushranger, The Law of the Range, The Desert Rider and Sioux Blood.)

War Paint also teamed McCoy with director W.S. “Woody” Van Dyke, who the new contract player recalled as, being “…annoyingly arrogant, maddeningly self-opinionated, damned sure of himself and utterly ruthless.” Nevertheless, McCoy conceded: “Van was a great director.” While Van Dyke was a demanding taskmaster, he and McCoy shared one thing in common. They wanted a high degree of realism in their productions. Although William S. Hart was touted as being the genuine article, “High Eagle” actually could claim he was the master of veracity. For instance, he collaborated with Van Dyke on War Paint’s script because the director contended the staff writers knew nothing about the subject. He rightly concluded that McCoy did. Indeed, McCoy’s movies rang with more authenticity than most other silent films.

Unfortunately, even McCoy eventually succumbed to the B-Western formula. After Metro failed to renew his contract, mainly because they refused to increase his pay from the $4,000 per film he was paid, he moved on to other studios. There he joined a litany of white-Stetson-wearing matinee heroes. Later he switched to his signature black hat to distinguish himself from the other good guys. Regrettably, as with many other nitrate pre-sound-era motion pictures, most of his early films no longer exist. The extraordinary samples of images in True West demonstrate his devotion to accuracy, which in the process, paved the way for hundreds of Hollywood horse soldiers who followed. He was the real McCoy.

Courtesy MGM

Courtesy MGM