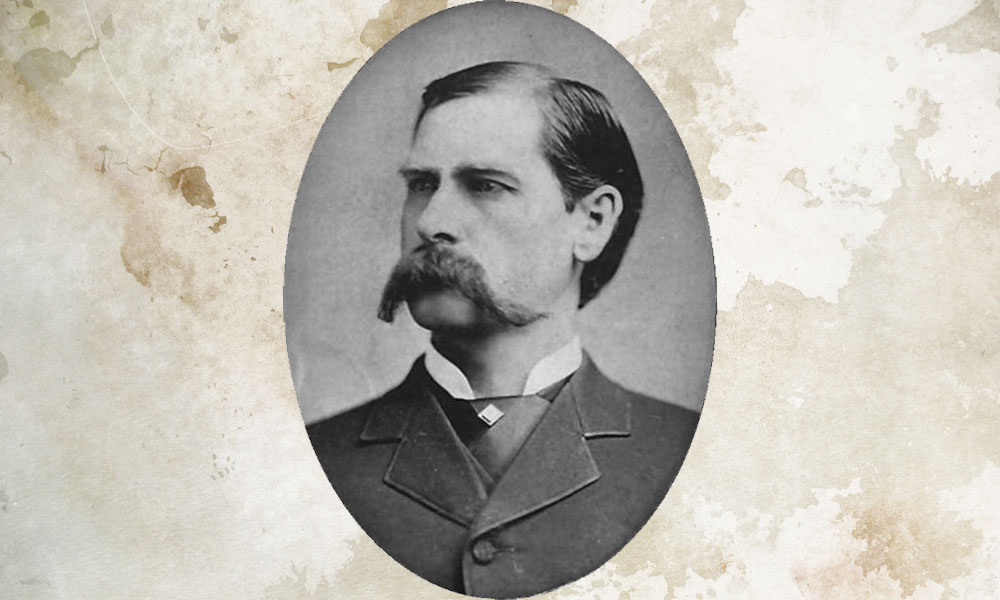

Almost five years had passed since the gas-lit world of saloons and gambling halls brought Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday together in Texas. They appear to have enjoyed each other’s company from the outset, but on the night of September 19, 1878, in Dodge City, Kansas, the bond between them was sealed when Doc saved Wyatt’s life in “a scrimmage” with Texas drovers that left one man with a bandaged head and a soldier shot in the leg.

Almost five years had passed since the gas-lit world of saloons and gambling halls brought Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday together in Texas. They appear to have enjoyed each other’s company from the outset, but on the night of September 19, 1878, in Dodge City, Kansas, the bond between them was sealed when Doc saved Wyatt’s life in “a scrimmage” with Texas drovers that left one man with a bandaged head and a soldier shot in the leg.

Wyatt’s gratitude for that night’s work explains much about his friendship with the well-educated but sometimes hot-headed and troublesome Georgian.

For his part, backing the Earps’ play became Doc’s habit in Tombstone, even before the October 26, 1881 street fight. He and Wyatt did have things in common. They were both gamblers, both fastidious dressers, both men who lived by their wits and their guns, but Doc was the son of good family whose ambitions were thwarted by disease while Wyatt was a would-be entrepreneur determined to improve his lot in the world. Doc fed Wyatt’s need for wit, intelligent conversation, and culture, while Wyatt and his brothers provided Doc with a sense of family and purpose. But the core of their friendship was an absolute and mutual conviction that they could count on one another no matter what.

In July 2001, co-author Chuck Hornung was in New Mexico, doing research for his book on the New Mexico Mounted Police. One Sunday, he decided to take a break from his labors and join his brother-in-law at Albuquerque’s big weekend flea market. While there, he found a copy of Miguel A. Otero, Jr., My Nine Years as Governor of the Territory of New Mexico, 1897-1906 (1940) at the bargain price of $7.50. Later, as he was examining his prize, he found in its pages the folded carbon copy of an undated, unsigned letter filled with potentially explosive new data on the Earp vendetta posse of 1882.

First, the most arresting find in this letter has been the subject of controversy and speculation for decades. Shortly after Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday arrived in Albuquerque, New Mexico, April 1882, a four-year period in which they had been extremely close came to an abrupt end. In May 1882, newspapers reported that Wyatt and Doc had quarreled in Albuquerque and that Doc and Dan Tipton had left the rest of the posse and proceeded to Trinidad, Colorado. What was the quarrel about? One tale, almost absurd, was told that the two men argued because Wyatt Earp had worn a steel vest at the Iron Springs fight with Curly Bill, and that Doc thought Wyatt should take the same chances as everyone else. A second hypothesis also had to do with the Iron Springs fight. In this explanation, Wyatt was upset that Doc and the other posse members took cover when the shooting began and left Wyatt exposed and fighting alone. A third, more general theory was that Doc got drunk and talked too freely about the events that had recently transpired in Arizona. This letter may finally put this question to rest.

Another important issue brought to light is the extent to which the Earps and Holliday had the support not only of local mining and business interests in Tombstone, but also of corporate interests including Wells Fargo and the Santa Fe Railroad. Wells Fargo had made an unprecedented public endorsement of the Earps on March 23, 1882, and rumors would later name Wells Fargo as a player in thwarting the extradition of Doc Holliday back to Arizona from Colorado to stand trial for the murder of Frank Stilwell. Denver newspapers speculated that powerful forces were at work to prevent Holliday’s forced return to Arizona Territory. Who were these forces and how far did their influence reach?

The recently discovered letter throws light on both of these questions and more. It follows here in full.

Dear Old Friend,

It was good to hear from you and to learn all is well in Albuquerque. Yes, I knew Wyatt Earp. I knew him to be a gentleman and he held a reputation of being an excellent law officer. I knew the Earp brothers first in Kansas, but did not [see] much [of] them after that time. My father knew them best. I knew Doc Holliday at Las Vegas and told that adventure in My Life on the Frontier [Vol.] I.

I tired [tried] to help them in their quest to stay in New Mexico following the Tombstone trouble. The Lake book you mentioned [Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal] did not relate the matter, Earp and Holliday and some others stayed in Albuquerque a couple of weeks while [New Mexico Governor] Sheldon and the powers of the Santa Fe [Railroad] and Wells Fargo tried to work out some kind of arrangement, [sic]

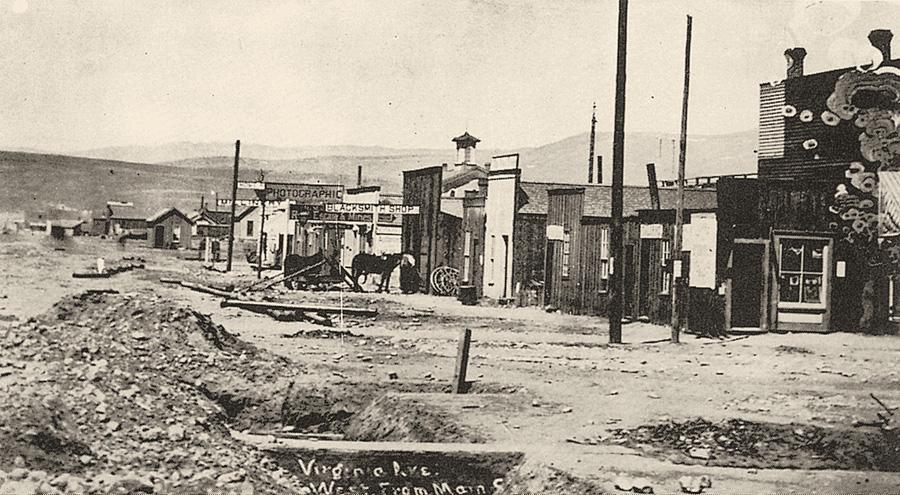

Earp (Wyatt) stayed at Jaffa’s home and the other boys were around town. Jaffa gave Earp an overcoat from his store, Earp’s had been ruined in a fight with the Cow-boys. I remember that cold wind even today. I do not remember that the boys had much money.

Father sent me to see to the comfort of the Earp posse because his railroad supported the boys. Earp had a long meeting with the president of Wells Fargo, but I can not say about the direction of the talk.

One afternoon I drove Earp and Jaffa to the river to see them building the new bridge. Earp remarked how it reminded him of the big bridge at Wichita. Some days later, Earp and Holliday had a falling out at Fat Charlie’s one night. They were eating when Holliday said something about Earp being a Jew boy. Something like Wyatt are you becoming a damn Jew boy? Earp became angry and left. Charlie said that Holliday knew he had said it wrong, he never saw them together again. Jaffa told me later that Earp’s woman was a Jewess. Earp did mu– (illegible/mezuzah?) when entering his house.

Wells Fargo arranged safety in Colorado and the road gave them passage to Trinidad. I remember that Blonger and Armijo kept watch over the boys. I was able later, when governor, to reward Armijo for that favor to my father. That is all I know about the Earps.

My health is not good at present. I spend much time confined to my bed. I am glad you found my new book of interest. My best to the Mrs. and season’s greetings to all.

Yours sincerely yours,

The internal evidence of the letter clearly identifies the writer as Miguel A.( “Gillie”) Otero, Jr., former governor of New Mexico Territory, and the author of four books, including the two which are mentioned in the body of the text, volume one of My Life on the Frontier, 1864-1882 (1935) and My Nine Years as Governor of New Mexico, 1897-1906 (1940). As Otero refers to the latter as “my new book” and mentions “season’s greetings,” the letter may reasonably be assumed to have been written in December 1940. This conclusion is supported by a second Otero letter which mentions Wyatt Earp, this one written to Watson Reed, August 17, 1940 (located by Allen Barra in 1998) which appears to have been typed on the same typewriter. Furthermore, the Albuquerque newspapers in 1882 confirm that Gillie Otero was in town while the Earp posse was there.

Though the primary focus of the newly discovered letter is Otero’s efforts to help the Earp party “stay in New Mexico,” Otero’s explanation of the quarrel that brought the dynamic Earp/Holliday duo to an end can’t be ignored. Otero’s comments regarding Jaffa and Earp supports his reason for the split—Jaffa was Jewish, and it appears from the letter that while staying in Jaffa’s home, Earp honored Jewish tradition. That Jaffa was a Jew and Wyatt was staying with him while Doc and the others were living in less spacious quarters may have contributed to Doc Holliday’s slur about Wyatt “becoming a damn Jew boy.”

Of course, Otero’s letter points to yet another issue which would explain why Wyatt took the remark so seriously. According to Otero, Jaffa told him that “Earp’s woman was a Jewess.” What makes this particularly compelling is the fact that the relationship between Wyatt Earp and Josephine Sarah “Sadie” Marcus in Tombstone was virtually unknown in 1940 when the letter was written, which means that the story had to come from someone with inside knowledge. That the explanation came from Wyatt’s host, who was himself a Jew, suggests that Wyatt discussed his relationship while at the Jaffa home.

Jaffa’s statement also contradicts recent arguments that the relationship between Wyatt and Sadie probably did not become a full-fledged affair until after they left Tombstone. Doc’s comment could have been merely a crude joke, or it could mean that Doc did not approve of Sadie. Doc’s relationship to Sadie is unclear, but while he was under arrest in Denver in May 1882, he said that Sheriff John Behan of Cochise County hated him because of a quarrel in which Doc accused Behan of gambling with money Doc had given Behan’s “woman.” Why Doc would have given money to Josephine Marcus was never explained. Finally, for the record, the proprietor of The Retreat Restaurant in Albuquerque in 1882 was nicknamed “Fat Charlie.”

Another intriguing comment concerns Jaffa’s replacing Earp’s overcoat because his “had been ruined in a fight with the Cow-boys.” This offers supporting evidence for Wyatt Earp’s claims concerning the killing of Curly Bill at Iron Springs. It is also true that, as Otero recounts, the new bridge over the Rio Grande was being constructed at the time the Earp party was in Albuquerque. Construction had begun in 1881, and it was not finished until December 1882.

In addition to the Earp-Holliday split, a major find in this letter is confirmation of widespread support for the Earp party. Otero identifies the parties involved in this effort as Governor Lionel A. Sheldon of New Mexico Territory, the Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, and Wells, Fargo & Co. Young Otero was working on behalf of his father, Don Miguel Antonio Otero, merchant, banker, and member of the board of directors and vice-president of the Santa Fe Railroad. Otero says further that Earp “had a long meeting” with John J. Valentine, general superintendent of Wells Fargo in Albuquerque. He concludes that Wells Fargo “arranged safety in Colorado” for the Earps, and that the Santa Fe Railroad provided the possemen’s passage to Trinidad and safety.

Can this letter’s contents be supported by other evidence? First, it is obvious that powerful forces were at work on behalf of the Earps even before they left Arizona. In addition to the official color and support afforded by their status as deputy U.S. marshals, they received financial support from prominent Tombstone businessmen and members of the Citizens Safety Committee, as well as help from the big ranchers and Wells Fargo. After killing Curly Bill, the Earp party found refuge at the Sierra Bonita ranch of Henry C. Hooker. While there, Dan Tipton brought them $1,000 from E.B. Gage, mining man and prominent vigilante; and Lou Cooley, a former stage driver who worked for Hooker and, at times, for Wells Fargo, delivered $1,000 from that company.

Stuart Lake, John Flood and Forrestine Hooker all claimed the Earps made one last visit to Tombstone for a meeting with the Citizens Committee. Hooker says that John N. Thacker of Wells Fargo was present. At that meeting, William Herring, attorney and spokesman for the vigilantes, advised Wyatt to leave Arizona until the furor died down and legal options could be weighed. Afterward, the Earps returned to Hooker’s ranch and made a final sweep of the area looking for Cow-boys before they left the territory. They were aided and abetted by Colonel James Biddle at Camp Grant, who allowed them to slip away although he knew them to be fugitives.

When Frederick W. Tritle arrived in Arizona Territory early in April to assume the governorship, he visited Tombstone where he stayed with Milton Clapp, one of the leaders of the Citizens Safety Committee, and conferred with William Murray, Tritle’s former business partner and another of the prominent vigilantes. As the Tucson Citizen reported, Tritle raised a posse to support Deputy U.S. Marshal John Henry Jackson and wired President Chester A. Arthur about “the utter failure of the civil authority and the anarchy prevailing; the international trouble likely to grow out of this cattle thieving along the border, the fact that business is paralyzed and the fairest valleys in the Territory are kept from occupation by the presence of the Cow-boys.”

Tritle would be the man who would send defective extradition papers to Colorado seeking the return of Doc Holliday after he was arrested in Denver in May 1882. Moreover, Governor Sheldon of New Mexico had a force in the field after the Cow-boys under Albert Jennings Fountain during the same period as the Vendetta ride. Finally, Wells Fargo’s support of the Earps never wavered. On April 14, 1882, Lou Cooley met John J. Valentine, the general superintendent of Wells Fargo, on the train in Benson. Afterward, Cooley was arrested in Willcox for “aiding and abetting the Earps.”

It appears now, based on the Otero letter, that Valen-tine proceeded directly to Albu-querque after meeting Cooley. The Albuquerque Evening Review, confirms Valentine was there on April 16 and 17. The Earps reached Silver City, New Mexico, on April 15, took the stage to Deming on April 16, where they caught the train to Albuquerque, arriving that evening. Stuart Lake’s notes at the Huntington Library say that Wyatt was met at the station by Frank McLain (McLean), later Wyatt’s associate on the famous Dodge City Peace Commission, who took them under his wing and later gave Wyatt $2,000. Whether this was a personal loan or McLain was acting on behalf of other individuals or organizations is not clear, but in light of Otero’s statement that he was sent to Albuquerque “to see to the comfort of the Earps,” McLain may well have been an agent.

Remarkably, upon arrival in Albuquerque, Wyatt visited local newspapers and promised interviews provided that the papers would not report his presence until after he and his men had left town. Neither the Morning Journal or the Evening Review mentioned that the Earps were in town until May 13, 1882, by which time the Earp brothers were in Gunnison, Colorado and Doc Holliday was en route to Denver. The Journal did deny that it had interviewed Earp, and the smaller Albuquerque newspapers have not been consulted, but the Earps were known to be in town which makes the silence nothing short of remarkable in light of the extent of press coverage of the Earp party’s movements.

Otero’s letter offers a clue to how that was accomplished. Henry N. Jaffa, the businessman mentioned by Otero, was the president of New Albuquerque’s Board of Trade, which acted as a quasi-government for the town. Sam Blonger, as marshal of “New Town,” was appointed to that office by the sheriff of Bernalillo County, Perfecto Armijo, and approved by the Board of Trade. The town marshal’s salary was paid by members of the Board of Trade, Jaffa’s organization. Both Blonger and Armijo are mentioned by Otero as keeping watch “over the boys.” Jaffa was a man who could make things happen.

The senior Otero’s position with the Santa Fe railroad lends further credence to the notion of brokered power on behalf of the Earps that eventually included the governors of Arizona Territory, New Mexico Territory, and the state of Colorado. Otero specifically states that Wells Fargo arranged “safety in Colorado,” and it is worth noting, in this respect, that Horace A.W. Tabor, mining magnate and lieutenant governor of Colorado, arrived in Las Vegas, New Mexico, the home of the ailing senior Otero, shortly after the Earps departed Albuquerque for Trinidad. Such a deal would also explain Doc Holliday’s public remarks in Colorado that he had already been “pardoned” and his surprise when he was arrested in Denver. Further, it would explain the subsequent efforts brought to bear on Doc Holliday’s behalf in Denver—which were so obvious they caused press comment—and why the Earps were never arrested in Gunnison.

Of course, further research must be done, not only on the substance of the claims in the letter, but also on the provenance of the letter itself before final conclusions can be drawn. Preliminary research substantiates those aspects of the account relating to times, names and places that can be validated from the public record. If the letter holds up under further scrutiny, it confirms that the Earps had the support of powerful organizations and individuals on their Vendetta ride. This support was sustained, in spite of the killings and that eventually thwarted efforts to return them to Arizona. It also suggests that the Vendetta ride was part of something much larger than the Earp-Clanton feud.

In light of other activities going on at the same time in both Arizona and New Mexico, such as Deputy U.S. Marshal Jackson’s operations in southern Arizona and Albert Fountain’s search for Cow-boys in New Mexico, as well as a presidential threat to use the army to restore order in Arizona Territory, these revelations point to a determined federal effort supported (or perhaps instigated) by powerful economic interests (big ranchers, railroads, mining companies, and Wells Fargo) and territorial authorities to suppress lawlessness in the Southwest.

On another level, the Otero letter provides circumstantial evidence supporting the description of the Iron Springs gunfight given by Wyatt, throws new light on the relationship between Wyatt and Sadie, and suggests that the reason that the relationship between Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday cooled was much more personal than previously believed. Taken together, if the revelations found in this letter hold up under further scrutiny, the letter will have to be considered a major find which fills in important pieces of the Tombstone puzzle. And note: you won’t be the only one with an all-new interest in flea markets.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –