Charley Parkhurst was the name;

Charley Parkhurst was the name;

Stage driving was the game,

But it wasn’t till he died,

Anyone knew he was a dame.

Okay, it’s a crude rhyme, but it does spotlight the story of the most famous Western woman who lived her life as a man. What most don’t realize is there actually were three Charleys—three unconventional women who disguised themselves to earn the freedom of trousers and escape the restraint of skirts.

Why they did it and how they pulled it off is an intriguing part of Western history.

“It would take courage, determination and stamina in any age for a woman to live as a man, but this was especially true in the inhibiting 1800s,” writes Frances Laurence in her 1998 Maverick Women. “To hide her gender would have necessitated being a ‘loner,’ trusting no one of either sex, guarding her identity as closely as if the law were after her.”

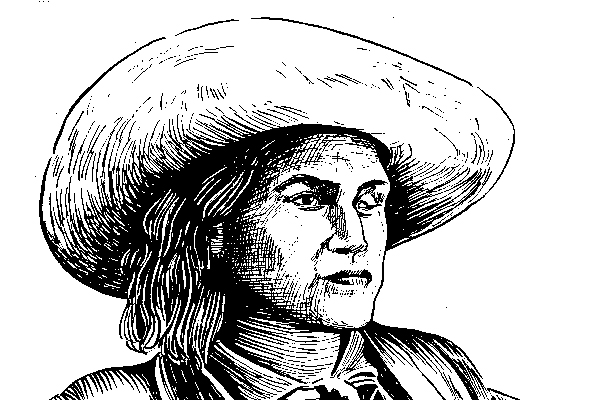

“Cockeyed” Charley Parkhurst

Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst was in her early teens around 1825 when she walked away from the orphanage where she’d grown up. She dropped the last four letters of her name, put on a set of boy’s clothes and began her life as a man.

Never again in over five decades would Charlotte answer to her name or her sex—she voted as a man, at a time when only men voted; she worked like a man and swore like a man and earned the respect a hardworking, horse-savvy man deserved.

Charley had a knack with horses and driving a team, allowing him to spend much of his life driving stagecoaches in California.

He was about five feet seven inches tall, weighed in at 175 pounds and adopted manly traits: he threw dice and played poker, he drank and argued politics, he cussed and chewed tobacco. He always wore gloves to hide his hands and was usually dressed in blue jeans and a double-breasted coat with a big leather belt.

“People remarked on the fact that Charley never allowed a woman to ride the top seat by his side, nor did he seek female companionship,” Laurence notes. “Once he even left a good Sierra run he’d held for three years because some of his female riders bothered him by speaking of marriage.”

Although after he died at 67 on December 22, 1879, some said they suspected he was a woman all along, it’s unlikely they held such a belief when they saw him handle a team. The prevailing thoughts on Charley Parkhurst were recorded by Western writer Joseph Henry Jackson: “Charley was as skillful, as resourceful and as hard-boiled as any driver in the Sierras.”

Six days after his death, the San Francisco Morning Call wrote this tribute: “He was in his day one of the most dextrous and celebrated of the famous California drivers … and it was an honor to occupy the spare end of the driver’s seat when the fearless Charley Parkhurst held the reins.”

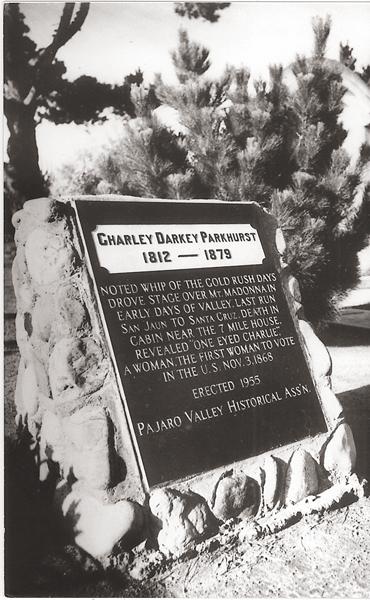

When Charley’s sex was revealed, the town of Soquel, California, honored her with a brass plaque for being the first woman to vote—the 1868 presidential election had recorded Charley’s vote as a man.

Mountain Charley

Revenge and the need to support her children drove widowed teenager Elsa Jane Forest to spend 13 years posing as a male.

Elsa had been raised by a rich “uncle,” who actually was her bachelor father, but she left home to marry a Mississippi riverboat pilot at age 12. By the time he was killed in a fight three years later, she had two children and no visible means of support. In desperation—and burning with a desire to revenge her husband’s death—she borrowed boy’s clothes and spent weeks practicing her new act.

She worked four years as a cabin boy on a riverboat. Between trips, she’d later write in her 1861 memoir, she’d put on women’s clothes and visit the children she’d left in the care of the Sisters of Charity.

She next became a brakeman on the Illinois Central Railroad, but she scurried away after discovering her conductor had suspected her disguise and intended to rape her. She wound up out West, where she worked her way into part ownership of a bar, sold out to buy a mule train business, which she made a success, then sold that to buy a saloon in Colorado’s gold mining country. It was there that she got the nickname “Mountain Charley.”

“It is needless for me to deny that during this time I heard and saw much entirely unfit for the eyes and ears of a woman,” she’d write of her days at the saloon, “yet when tempted to resume my sex, I was invariably met with the thought—what then?”

Along the way, she twice ran into the man who’d killed her husband. During their first encounter, they wounded each other in a street gunfight. The second time they met, she wounded him and walked away unscathed—she was happy to hear that not long after, he sickened and died.

She eventually remarried and was reunited with her children and father, ending her life as a man. Although she characterized her 13 years as a man as “deeply disturbing,” her autobiography also notes that it was the only way she could have earned grand sums to support and educate her children.

Another Mountain Charley?

A second woman to call herself “Mountain Charley” is known only through the writings of George West, who told her story in newspaper articles in Colorado’s Golden Transcript. He claimed she had been jilted by her husband and disguised herself as a man to track him down, but she soon discovered that her new identity allowed more freedom and wage-earning possibilities.

West recounted how he had helped save her from a wild bunch who’d discovered her true identity and intended her harm; how she shared her life story with him on the promise he wouldn’t publish it for 25 years—a pledge he honored; and how after he finally told her story, she sent him her diary to recount her adventures during the Civil War.

The stories sound almost too fanciful to be true—at one point, the disguised boy disguised himself as a girl to infiltrate the Confederate Army. But West wrote that her courage earned her a commission as First Lt. Charles Hatfield.

There were probably more women like these three, who traded their identity for an easier life—a life of opportunity and money; a life the West generally hoarded only for its men.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy County of Santa Cruz –

– Courtesy Pajaro Valley Historical Association –