Frankly, I don’t get re-enactors. Like that overweight, redneck Civil War buff I saw years back, firing his musket, then yelling at advancing Yankee re-enactors: “Eat [bleep] and die!” I can’t see a Reb in 1863 being so plump.

Frankly, I don’t get re-enactors. Like that overweight, redneck Civil War buff I saw years back, firing his musket, then yelling at advancing Yankee re-enactors: “Eat [bleep] and die!” I can’t see a Reb in 1863 being so plump.

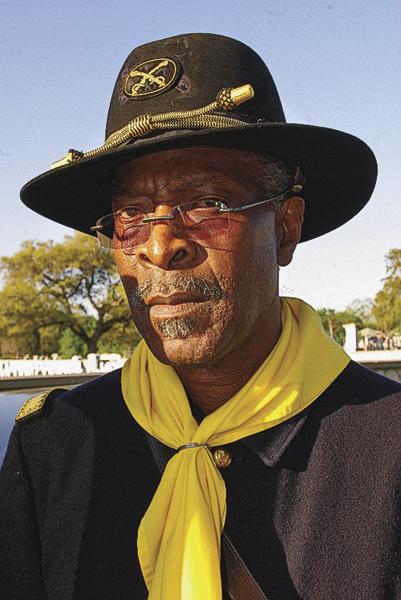

These guys, however, I understand and like. But they’re not “re-enactors.”

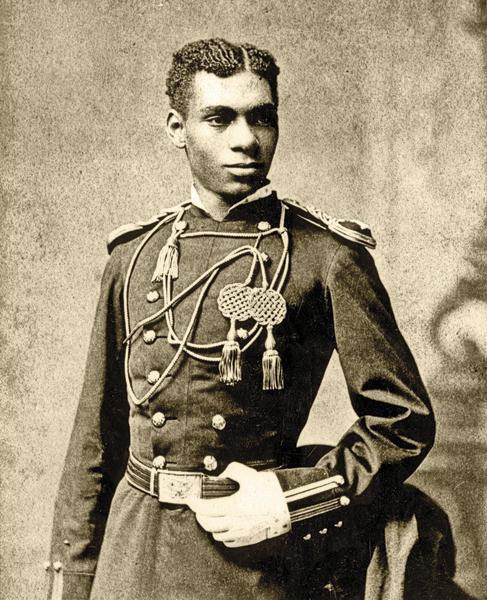

Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper greets me at the San Antonio National Cemetery. You probably know Flipper, the first black graduate from West Point. Born into slavery in Georgia in 1856, Flipper was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1877 and served in the 10th Cavalry, including the campaign against Victorio’s Apaches. Court-martialed in 1881, he was dishonorably discharged, but in 1999, President Bill Clinton gave Flipper a posthumous pardon.

Actually, Flipper is Turner McGarity, a member of the Bexar County Buffalo Soldiers Association, dedicated to honoring the black soldiers and Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts who served in the post-Civil War West. Eighteen earned the Medal of Honor.

Just don’t call these men “re-enactors.”

“We’re not a re-enacting group,” McGarity says. “We spread history that has been left out of the books.”

The “Buffalo Soldiers” Begin

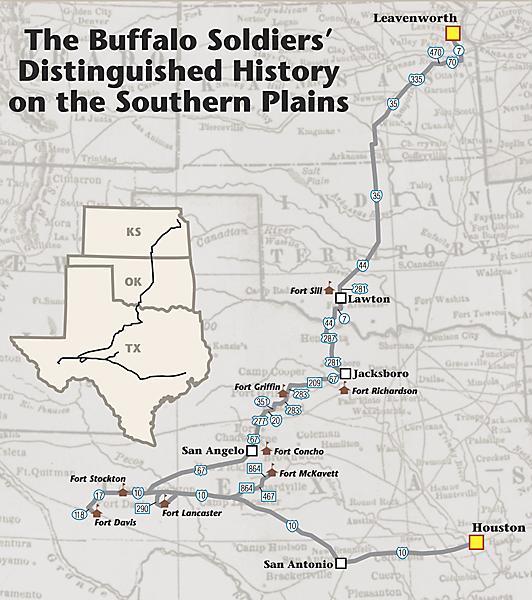

The post-Civil War history of the “Buffalo Soldiers” began on July 28, 1866, when Congress authorized the formation of six all-black regiments (two cavalry, four infantry), the first black regiments created since the Civil War, which saw 175 such regiments in the Union Army. Those six units would be reduced to four regiments, the 9th and 10th Cavalries, and the 24th and 25th Infantries, history’s “buffalo soldiers.” Most of the 9th, organized in New Orleans, would train in San Antonio. The 10th would set up shop in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

The latter’s as good a place as any to start this trip.

That’s because the Frontier Army Museum tells the story of the Army (1804-1916) and the fort (1827-today), and its collection of horse-drawn vehicles is considered among the world’s best. Buffalo Soldier Memorial Park, dedicated in 1992, is beautiful, inspirational and educational.

Entry to the museum and memorial is free, but photo identification is required for entrance to the still-active fort.

Benjamin Grierson commanded the 10th. Edward Hatch commanded the 9th. Not all officers welcomed the opportunity to command blacks—many of whom were recently freed slaves. George Custer rejected a lieutenant colonel’s commission in a black regiment (he got one, instead, in the all-white 7th). Frederick Benteen decided he’d rather be a captain in the 7th than a major in the 9th. On the other hand, Wesley Merritt became the 9th’s lieutenant colonel before being promoted to the 5th Cavalry’s command in 1876.

Of course, the Army—then, like today—moved around, so I’m transferring to Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma.

Established in 1869 near the Wichita Mountains, the 10th Cavalry pretty much built Fort Sill, but these soldiers weren’t just carpenters and masons. In 1871, when General William T. Sherman ordered the arrest of Kiowa leaders Satank, Satanta and Big Tree for their part in the so-called Warren Wagon Train Raid near Jacksboro, Texas, it was the 10th that sprung the trap and prevented more bloodshed, surprising the Kiowas and forcing Satanta to surrender. The fort’s museum is tops, and a who’s-who of Indians rests in the post cemetery.

Black Soldiers on the Texas Frontier

Black units would be stationed across much of Texas, so get ready to travel. Fort Richardson in Jacksboro honors the 10th and 24th soldiers stationed here. Blacks served at Fort Griffin, north of Albany. Both posts are now state historic sites, and the latter boasts an outstanding visitors center that opened last year. (Griffin is also home to the state’s official longhorn herd.) Yet one of the best-preserved posts is in San Angelo, and Fort Concho, a national historic landmark, is a must.

Concho was home to the 10th—and still is. I’m greeted by three members of the Fort Concho Buffalo Soldiers, organized in 1987 for living-history programs.

If you believe the legend, with racial discrimination unchecked in post-Civil War Texas, black soldiers were given inferior equipment and poor livestock. There’s just one problem.

“It’s not true,” Fort Concho manager Robert Bluthardt says.

William A. Dobak (with co-author Thomas D. Phillips) challenged most of those “facts” in their 2001 book The Black Regulars, 1866-1898. They even argue that the term “buffalo” was considered derogatory in those days, but there’s no denying that today black interpreters and soldiers carry that label with extreme pride. The Fort Concho Buffalo Soldiers certainly do. But…

“You have soldiers serving on the frontlines,” Bluthardt says. “You’re not going to give them inferior weapons, and their horses were no poorer than those issued to most white regiments.”

Injustice on the Frontlines

Which isn’t to say that the soldiers did not face extreme racism.

In 1881, a white sheep-man murdered an unarmed black soldier in a San Angelo saloon. Enraged black soldiers demanded justice, reportedly even storming the town and firing shots into several buildings before Grierson managed to prevent more bloodshed. The white Texan sheep-man was later tried and, no surprise, acquitted.

Flipper’s fight with racism seems equally unjust. So I’m off to Fort Davis National Historic Site in the beautiful Davis Mountains.

Established in 1854, Fort Davis had been regarrisoned and rebuilt in 1867 by the 9th under Merritt’s command. Flipper, who had also served at Sill and Concho, arrived at Fort Davis in 1880. Former 24th Infantry commander William R. Shafter, then leading the 1st Infantry, took over as the fort’s commander in 1881. When commissary funds came up missing, Flipper tried to hide the shortage from his tough disciplinarian commanding officer. That led to Flipper’s arrest, court-martial and dismissal for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentlemen (he was cleared of the embezzlement charge). Many historians note that white officers would not have been kicked out of the Army for such an offense.

Honoring the Valiant

From Davis, I head east—with brief stops at forts Stockton (reestablished by the 9th in 1867; run by the city today), Lancaster (the park ranger is sure happy to see me, or any visitor) and McKavett (which Sherman called “the prettiest post in Texas”). I could hit even more forts where blacks served, but I have a date at San Antonio National Cemetery.

We solemnly walk to the monument inscribed “To the Unknown Dead.” Not all of them are unknown today. A plaque below the memorial names several black soldiers who died during the Indian Wars.

More than 280 buffalo soldiers are buried in this cemetery. So is John Bullis, who commanded the Seminole-Negro Scouts during the Indian Wars.

“All gave some,” says McGarity, a veteran of the Vietnam War and retired Army sergeant major. “Some gave all.”

The Bexar County group is trying to raise funds to open a buffalo soldiers museum at Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Park near the cemetery. Of course, there’s already one in Houston, my last stop. There, Captain Paul Matthews, collector/founder/chairman and tour guide of the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum—and a Bronze Star recipient during Vietnam—personally shows me his “dream-come-true.” I also score some Buffalo Soldiers Barbecue Sauce. He refuses, however, to share his recipe.

This museum honors not just the blacks who fought in the West, but all wars, from the American Revolution to today. Its exhibit on the Houston Riot of 1917, an ugly event that led to the execution of 19 black soldiers (63 others received life sentences) for mutiny, is particularly disturbing.

Yes, Matthews says, the focus here is on blacks, but this isn’t just a “black” museum.

“Visitors learn about the black experience in the military,” he says, “and the sacrifices they’ve made. But they also learn about this country.”

Johnny D. Boggs can’t watch the 1964 movie Rio Conchos, co-starring NFL star Jim Brown as a black cavalry sergeant in post-Civil War Texas, enough.

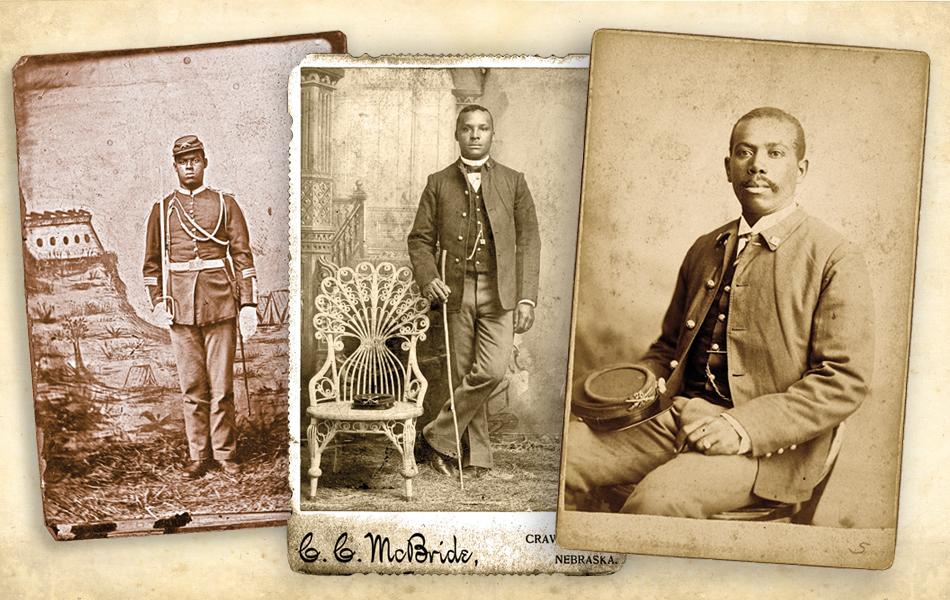

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy U.S. Military Academy Library –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All photos courtesy Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy The Buffalo Soldiers National Museum –