“I have been nearly driven to distraction!”

“I have been nearly driven to distraction!”

So said Victoria Zaff Behan, with the culprit being her well-known husband, John Harris Behan. This was in 1875 when, after six years of a more-than-rocky marriage, the lady decided to call it quits.

Victoria had already seen her share of struggles. She hardly knew her father, who had left her German immigrant mother, Harriet (maiden name unknown), after the birth of her first two children, Benjamin, around 1847, and Catherine, in 1849. Sans husband in 1850, Harriet moved with her kids from Missouri to live with Leopold and Catharine Zaff in Jefferson, Indiana, before she left for California. She gave birth to Victoria in 1852 and Louisa in 1854. By 1860, Harriet and her daughters were living in the gold mining camp of Little York in Nevada County, while Benjamin stayed with the Zaffs in Indiana.

The identity of Victoria and Louisa’s father remains a mystery. The census in Little York identifies Harriet as a widow, but clues are scant as to the identity of her husband. He may have been Godfrey Zaff, a fellow German, who was living in a Sacramento boarding house in 1850. The census that year indicates Zaff was married and labored as a “cutter of garments.” Perhaps Harriet and Godfrey got married in Indiana, then he went to try his luck at gold mining and later sent for her and the kids. Godfrey died in April 1860 in Nevada City, roughly seven miles from Little York.

Five months later, Harriet married John Bourke in Red Dog, located a mile or so from Little York. Bourke was one of thousands of Irish immigrants who had joined the Forty Niners flocking to California’s goldfields. A son, John, was born to the Bourkes in 1862. The family next spent time in Mohave County, Arizona Territory, before relocating to the budding city of Prescott in the winter of 1864.

In Prescott, Bourke found work managing the Quartz Rock Saloon. Between 1864 and 1867, he also joined the Society of Arizona Pioneers (today’s Arizona Historical Society), served as Yavapai County sheriff and was ultimately elected county recorder. For the first time, Victoria experienced a stable family life. She attended school, enjoyed her stepfather’s fine reputation in town and became acquainted with Deputy Sheriff Johnny Behan.

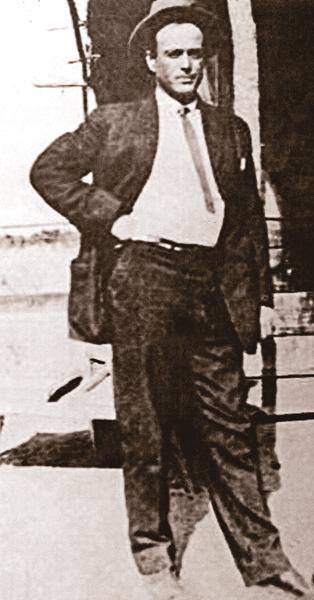

Behan, born in 1844 to Irish immigrants in Missouri, had also been to California. He joined the Union during the Civil War before serving as a clerk for Arizona Territory’s first legislative assembly in Prescott. In 1866, Bourke appointed him deputy sheriff, and Behan became popular with the denizens. A September 1867 edition of the Arizona Miner, Prescott’s newspaper, wrote of Behan’s journey to visit family in Missouri: “We wish you a pleasant trip, Johnny, and hope you will soon return in company with a better half.”

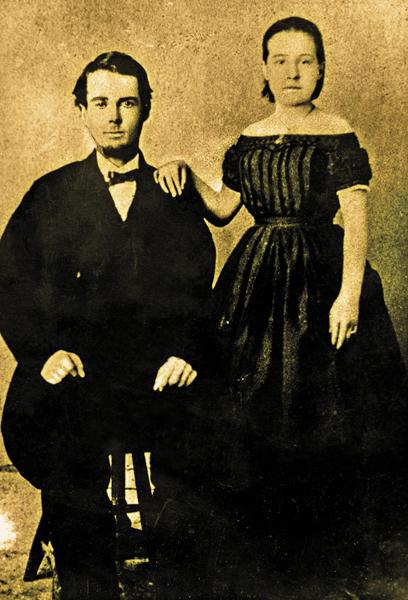

Behan’s “better half” would turn out to be Victoria Zaff. A couple of career mistakes aside, Behan seemed a good prospect for marriage. He had a great job and was well liked. Besides, she had one more good reason to marry him: Victoria was pregnant. The couple exchanged vows in far-away San Francisco, California, in March 1869. Their daughter, Henrietta, was born in June. The couple hoped nobody would do the math. They didn’t, at least publicly.

Soiled Doves on Whiskey Row

The family Behan became a respected presence in Prescott. In January 1870, the Arizona Miner noted the couple was building a stylish home on Capitol Hill, “one of the prettiest spots on the town site.” In July 1871, a second child, Albert Price, was born. Over the next two years, Behan was elected sheriff and appointed to the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Arizona.

Gradually, however, Behan began spending more and more time away from home. Victoria became aware that her husband favored Prescott’s Whiskey Row and its adjoining red light district. Victoria later claimed she knew all along that her husband “openly and notoriously visited houses of ill-fame and prostitution….”

The marriage crumbled further when Behan lost his re-election campaign for sheriff in 1874. On those occasions when he managed to make it home from Whiskey Row, Victoria remembered their terrible fights. During those times, Victoria claimed, Behan would approach her in a “threatening and menacing manner calling me names such as whore and other epithets of like character and by falsely charging me with having had criminal intercourse with other men, threatened to turn me out of the house, quarreling with, and abusing me, swearing and threatening to inflict upon me personal violence.”

Perhaps such an argument sent Behan into the arms of prostitute Sadie Mansfield in December 1874. There, Victoria said, he “did consort, cohabit and have sexual intercourse with the said [woman]…openly and notoriously causing great scandal…all of which came to the knowledge of this plaintiff.”

The Arizona Weekly Miner yielded no clues to the Behan’s failing marriage in the coming months, reporting instead on Behan’s prospecting efforts in Mohave County and daughter Henrietta making the honor roll at school. But Behan’s discrepancies were outed on May 22, 1875, when Victoria filed for divorce.

Ugly Secrets Come Out

She was granted one in June and received custody of her children, plus child support—but for Albert only. Naturally, the glaring crossing out of Henrietta’s name on the divorce record led rumors as to why. The ugly secrets that had been harbored within the Behans’ private circle were now on public display for all to see.

Local newspapers declined to comment on the divorce, but Victoria could not have missed the articles about Behan’s continued successes in law enforcement and politics. The newspapers were good to Victoria too, commenting on her charitable efforts and complimenting her family. “We have known [Mrs. Bourke] and her fair daughters to be industrious and an ornament to our good society,” praised The Weekly Arizona Miner in December 1876.

The Behans’ separate lives were forced to come together once more when Henrietta succumbed to scarlet fever in March 1877. Albert was also afflicted, but escaped with a hearing impairment. From then on, Behan remained much a part of Albert’s life. During an excursion in 1879, “Mr. Behan took his little son Albert with him, and will in a short time place him under the care of an eminent physician in San Francisco for the purpose of having him treated for a slight deafness, occasioned by a severe sickness two years ago,” confirmed The Weekly Arizona Miner.

Victoria continued rebuilding her reputation. Memories of her scandalous divorce were fading. In June 1879, Lily Fremont, daughter of Gov. John C. Fremont, noted in her diary that “Mrs. Behan, Mrs. Luke and Mrs. Rodenburg called.” Victoria was moving on with her life. Behan, meanwhile, was rescued from an angry mob of Chinese men in late 1879. Perhaps this embarrassing incident inspired him to open a saloon in Tip Top, a budding mining community in the Bradshaw Mountains about 25 miles south of Prescott.

Behan was still in Tip Top when the census was taken in June 1880, as was the notorious Mansfield with whom he had cavorted in Prescott. As for Victoria, she and Albert were still living with Harriet Bourke in Prescott. Victoria may have been blissfully unaware that her ex was pursuing a new love interest, Josephine Sarah Marcus. (Some historians believe Josie and Mansfield were the same woman.) If Behan told his ex-wife about his additional plans for another visit to San Francisco, California, he probably left out that he was going there to give an engagement ring to Josie and convince her to join him in Arizona.

Where’s Albert?

Victoria let Albert live with his father in Tombstone, but she may not have done so if she had known of Behan’s plan. Behan and son arrived in Tombstone in September 1880 and awaited Josie’s arrival in December. At the Grand Hotel where Behan bartended, Josie cared for Albert when his father was away. “I came to love him as my own,” she later said of Albert. “He was the only child I ever had in any sense of the word.”

Next, Behan and his new flame made plans to procure a house where they could live with Albert. Victoria was likely unaware of the plan or that the new “Mrs. Behan” had taken Victoria’s nine-year-old son to his hearing specialist appointment in San Francisco. Upon returning to Tombstone, however, Josie found Behan with another woman. Josie’s ensuing breakup with Behan landed her in the arms of his political adversary, lawman Wyatt Earp.

In August 1881, the local paper noted that Victoria had taken a trip to Mohave County, “visiting her sisters, cousins and aunts.” The reason for the trip may have been to retrieve Albert, as he was not mentioned as being in Tombstone during the famed shoot-out at the O.K. Corral a few months later.

Albert would have arrived in Prescott in time to attend his mother’s wedding to Charles Randall on September 15. Randall was a hardware merchant who, by all appearances, was much better suited for Victoria. Heartbreak came, however, when the Randalls tried for children. A daughter was stillborn in April 1884 and another baby died in November. A son, Owen Miner, was born in 1885, but lived just over a year. Victoria overcame her grief by focusing on Albert, who was sent to a California college in 1888.

In 1889, the Randalls were living at the Congress Mine when Victoria died suddenly on May 15 from “an attack of acute rheumatism.” The lady would have appreciated her epitaph in the Prescott Courier, which read, in part, “She was a good, true woman and friends, of which she had a great many, will be greatly grieved over her loss.” Pallbearers at her funeral included Yavapai County Sheriff “Buckey” O’Neill and former Prescott Mayor Morris Goldwater.

Randall remained in the town of Congress, where he was elected postmaster in 1891. He eventually remarried and returned to Prescott. As for Albert, Victoria’s only surviving child maintained relationships with his family up to their deaths. He also pursued a career in law enforcement. Between 1894 and 1922, Albert worked for the U.S. Customs Houses in Nogales, Yuma and Ajo. Beginning in 1897, his job included working as an undersheriff in those towns. He was still employed as such in 1912, when his father died in Tucson.

Visits with the Enemy

From 1918 to 1922, Albert gained respect as a U.S. marshal in Ajo. In 1926, as reported by Josie and others, Albert visited Josie and Wyatt at their Los Angeles home (the two were considered common law-married at that point). During the visit, Albert warned Wyatt that Billy Breakenridge, a former deputy sheriff under Behan, was writing a book with the intention of making Wyatt look bad (the tome, Helldorado, was published in 1928).

“It seems a bit strange as I think of it,” Josie later commented, “that the son of Sheriff Behan should show this interest in the reputation of his father’s political enemy. But the character of the two men—Wyatt Earp and the sheriff’s son—answers that, and the friendly gesture on the part of the younger man is a compliment to both.”

Ten years later, Josie visited Albert in Tucson on the way to Tombstone for a “research trip.” With her were Harold and Vinnolia Earp Ackerman, who, with Mabel Earp Cason, planned to write a manuscript about Wyatt. Neither Breakenridge, the Ackermans, nor Cason interviewed Albert. If they had, he might have mentioned his mother, Victoria—although Josie would have probably prevented such information from appearing in any public works.

With the deaths of Victoria’s sister Louisa in 1934 and her last husband, Charles Randall, in 1942, fewer people remained who personally knew Victoria. Alone, with no immediate family, Albert retired to the Arizona Pioneers’ Home in Prescott. When he died in 1949, his death certificate listed his parents as “unknown.” Even Albert took the secret of his parents’ scandalous divorce to the grave.

Jan MacKell Collins has written two books about prostitution history in the Rocky Mountains and, most recently, The Hash Knife Around Holbrook. Her latest book, Wild Women of Prescott, will debut this year.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Lydia Gray –

– Courtesy Lydia Gray –

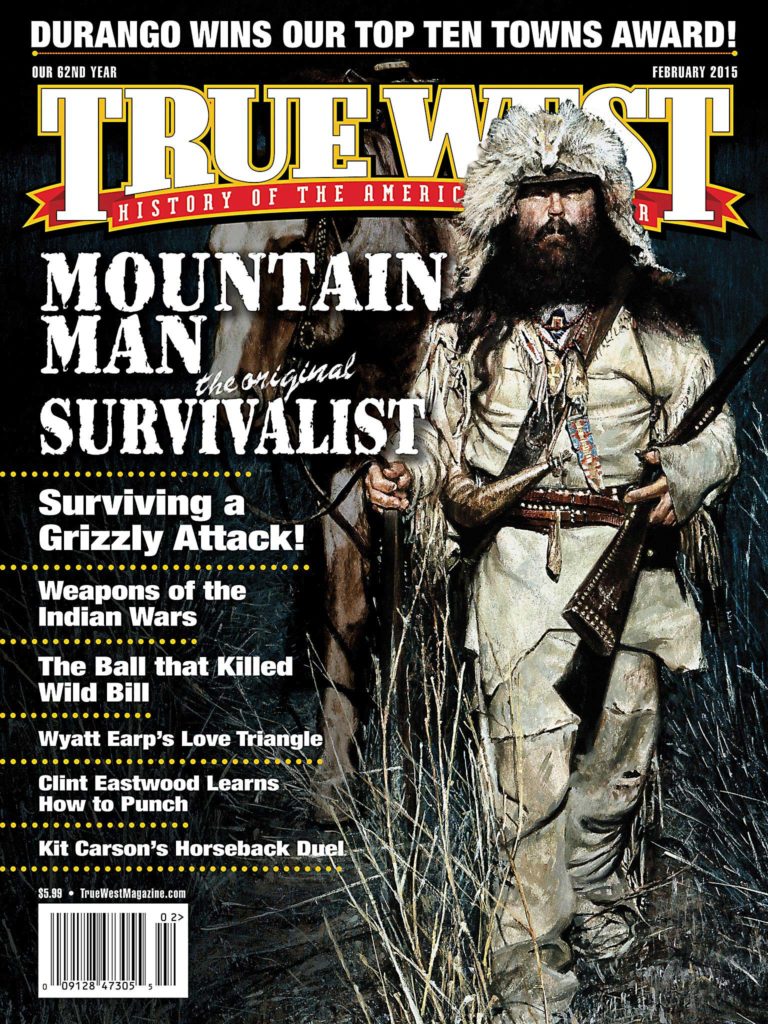

– Courtesy University of Arizona Special Collections –